My Claremont Year- Inferno (Sept/Oct)

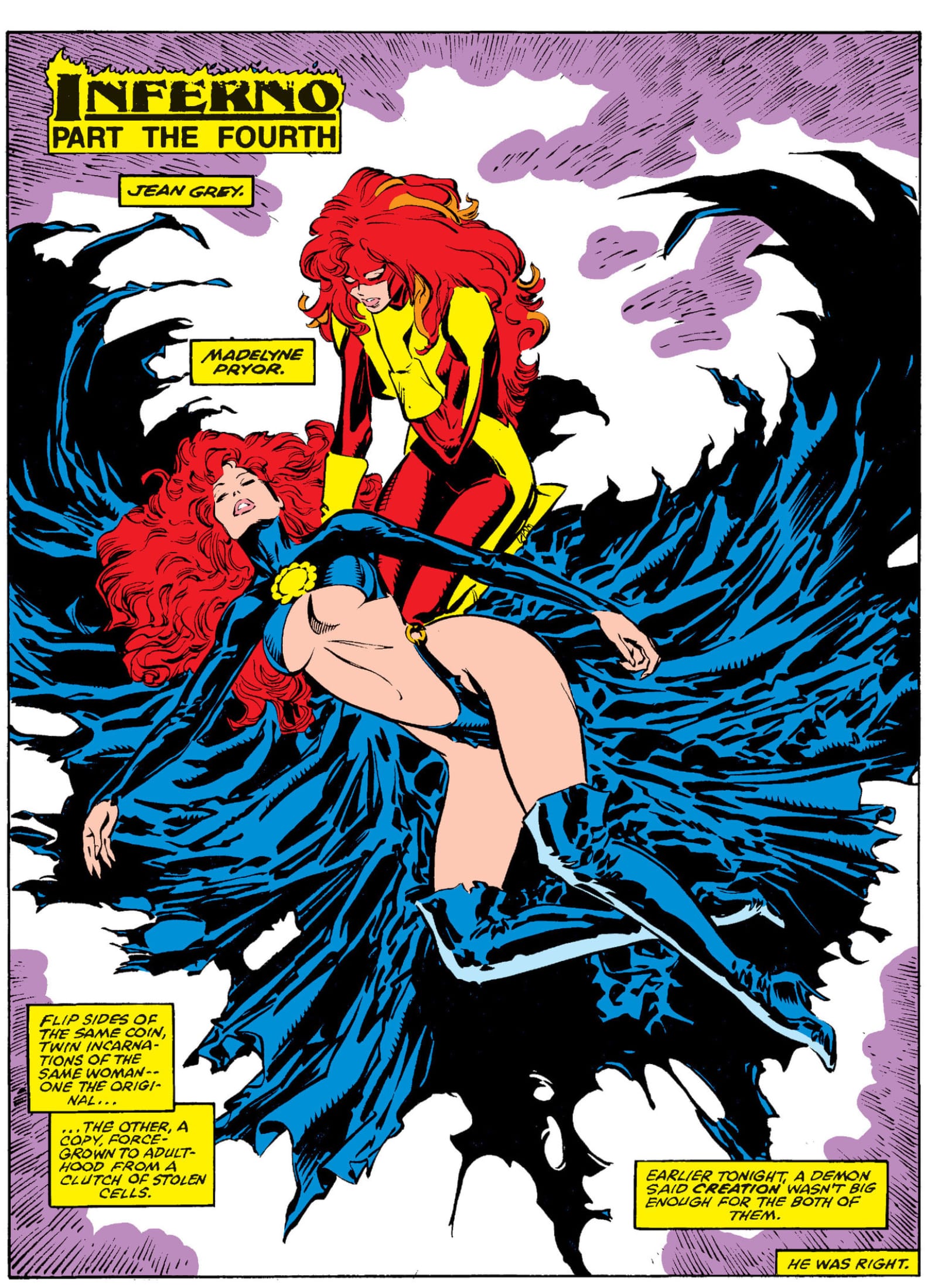

Madelyne Pryor died in Inferno so that Jean Grey could live (and die and live again.)

Around the end of 2022 a thought struck me; have I ever read all of Chris Claremont’s X-Men? I think I’ve collected it all in one form or another (or even multiple forms) but there’s a point in the mid-1980s where a lot of it becomes fuzzy in my memory. I probably read it when it was coming out but more out of the inertia of collecting than any love of it. So armed with several omnibuses, Marvel Unlimited, and whatever back issue diving I need to do, I’ve set the goal to read his 16-year run on X-Men, New Mutants, and other related books, probably also eventually including some Louise Simonson New Mutants and X-Factor here as well since the series are so tied together.

As much as this is to check out these stories again, I want to see if there’s a completeness to the story that Claremont was telling, starting with his first issue, X-Men #94 (1975), and extending all the way through X-Men #3 (1991). Maybe by the end of 2023, I’ll have some kind of grand unified theory of Chris Claremont’s time on the book or maybe I’ll just have read a lot of comics that range from “not bad” to “what were they thinking?”.

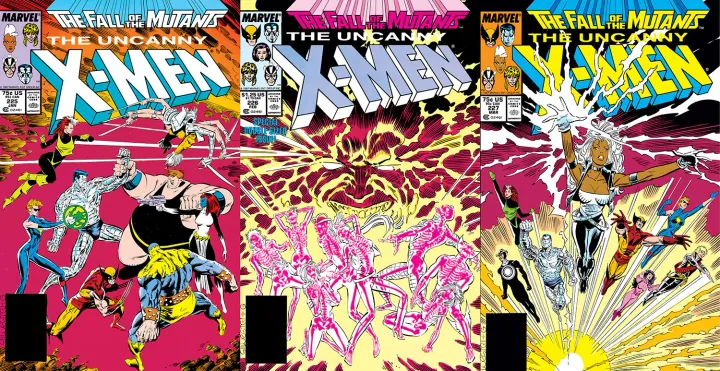

- Uncanny X-Men #228-243

- New Mutants #62-73

- X-Factor 27-40

- X-Terminators 1-4

- Excalibur: The Sword is Drawn

- Excalibur #1-7

- X-Men Annual #12

- Marvel Comics Presents #1-10

- Wolverine #1-10

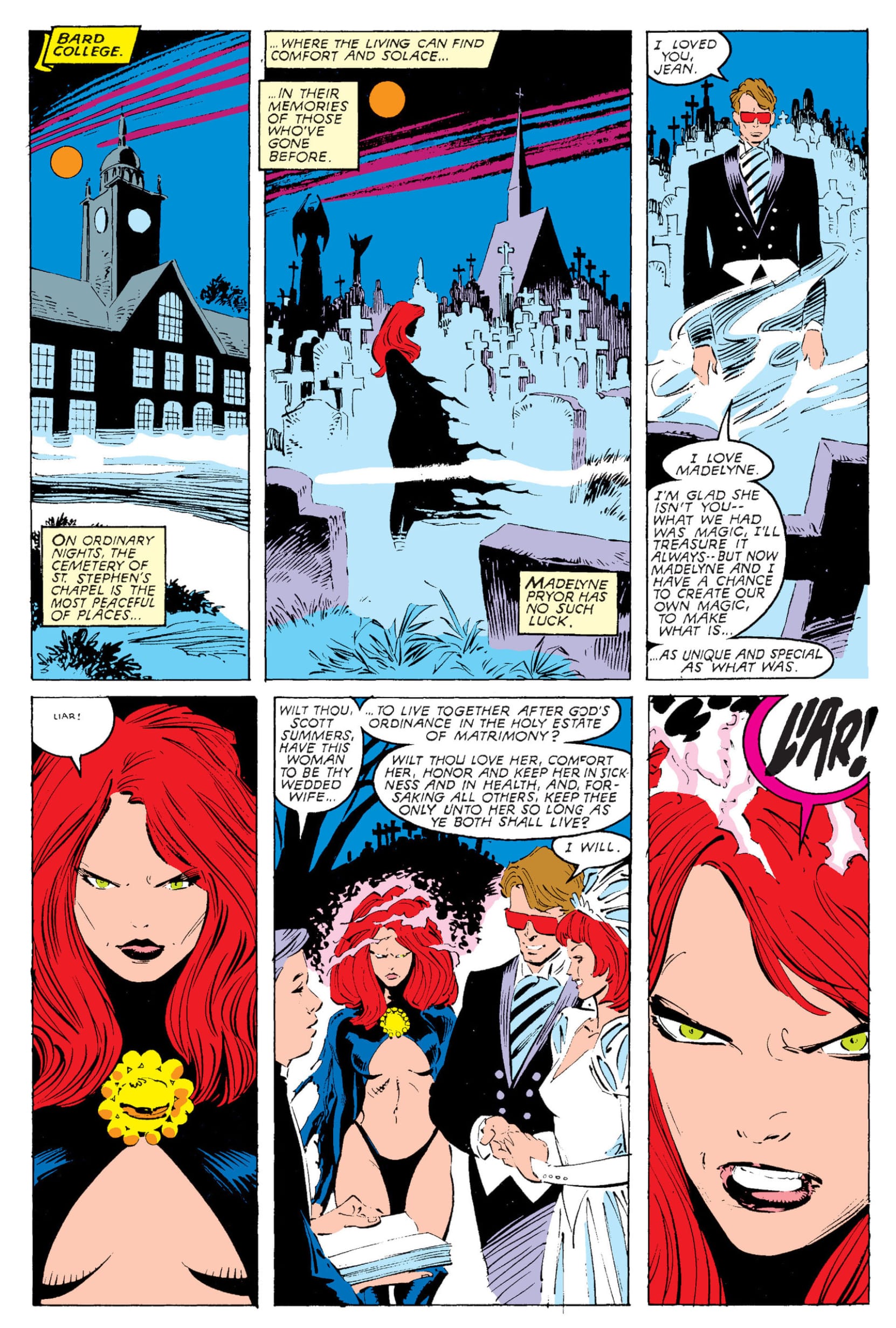

Inferno is a story that feels like it shouldn’t have to exist because its lead character Madelyne Pryor shouldn’t exist. Maybe it was clearer when Chris Claremont created her as a potential love interest for Scott Summers as she filled in this Jean Grey-shaped hole in the narrative, right down to her red hair that she conveniently shared with the one-time Phoenix. Madelyne was this character about legacy who had none of her own. Her legacy was going to be the future that she built with Cyclops, including their newborn son Nathan Christopher Summers. It made sense to try to move Cyclops into a different role in the X-Men story. And then someone at Marvel got the bright idea that Jean Grey was never the Phoenix and that they could bring Jean back from the dead (or maybe it’s from the mostly dead.) So if the original was back in the pages of X-Factor, what purpose did the almost carbon copy of her fill anymore?

So Chris Claremont turns her into a villain but let’s get back to that a bit later.

Following Fall of the Mutants, Claremont has a clean slate— a new headquarters, a team of still-fresh characters as well as a few of the old guard hanging around, and a break from most of the other X books that seemed to be everywhere at the time (or maybe it just feels that way looking back 30+ years.) And this is what everything from the Mutant Massacre through Fall of the Mutants had been working towards, some kind of freedom from the mutant machine that he had started. Claremont could start introducing new villains like the Reavers and new concepts like the country of Genosha to the story. He wasn’t tied to the old school, the old villains, or even the same old struggles anymore. Except there was still one dangling thread out there from the old days— Madelyne Pryor.

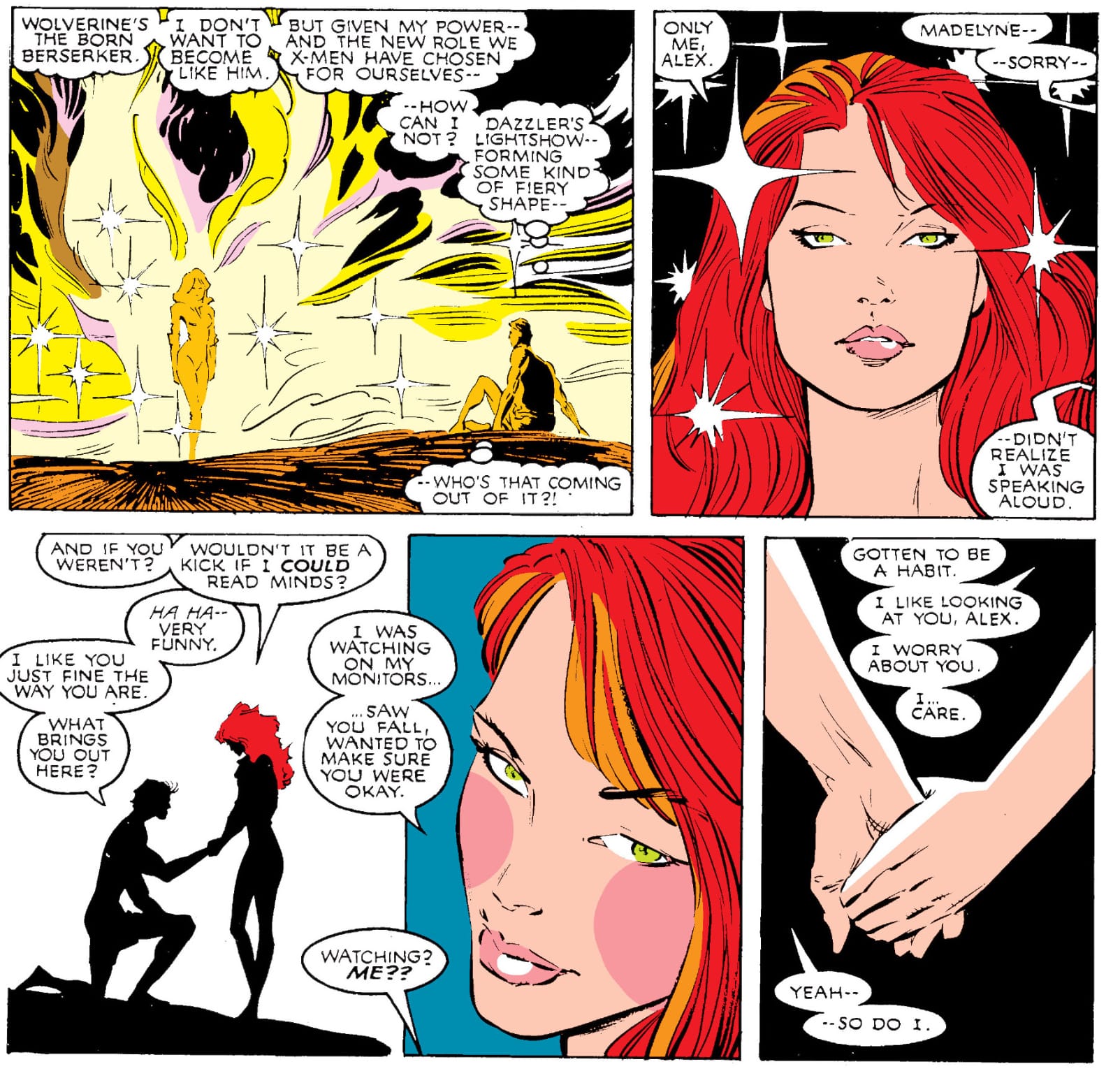

During the Outback era that preceded Inferno, Madelyne becomes this weird wildcard. She was introduced as a love interest for Scott Summers, discarded when Jean Grey returned from the dead, and then recast as some kind of wolf-in-sheep’s-clothing antagonist, slowly seducing Scott’s brother Alex. Harkening back to the soap opera-like days of the book, all the characters seem as horny as they are heroic now. This period of Claremont’s run plays with this sexual tension between the team, their enemies, and all of the supporting characters as well. Madelyne goes from the nice girl to the all-powerful femme fatale as Hell comes to NYC.

Running through New Mutants, X-Factor, and Uncanny X-Men, Inferno is this story of three women: Jean Grey, Madelyne Pryor, and Illyana Rasputin. Claremont and fellow X-writer Louise Simonson use this story of all hell breaking loose to take these Claremont characters (and yes, by now Jean Grey counts as a Claremont character as much as she does a Lee/Kirby character) to the conclusions that their stories need. In New Mutants, Simonson’s Illyana story acts as a fitting bookend for Claremont’s Magik miniseries, giving the character a resolution to the lost years that were stolen from her in limbo. It’s a deserved satisfactory ending for the character who both Claremont and Simonson spent so much time exploring her struggles between being an angel and a demon. Her story is central to Inferno, the story of a young woman torn between these opposite aspects of her life.

Claremont and Simonson then mirror that story in Madelyne and Jean through X-Factor and Uncanny X-Men, looking at how these two women are the living embodiment of opposite aspects of a singular life. These aspects are depicted in the angel/devil dialectic that Claremont explored in Jean Grey back in The Dark Phoenix Saga. Inferno is practically that older story revisited. In the original, Claremont used Jean Grey to explore both abuse and power and that’s pretty much what he and Simonson are doing here. Exchange The Dark Phoenix Saga’s Mastermind with Inferno’s Mister Sinister and you can see that these stories are essentially stories of men manipulating women for their own desires and needs. That’s even what Illyana’s story is. Whether it’s Mastermind, Mister Sinister, or the Limbo demons S’ym and N’Astirh, these are stories about manipulation and abuse.

You can trace these themes back to the early days of Claremont’s writing on the X-Men, such as Uncanny X-Men #111 when the villain Mesmero manipulated the team into thinking that they were carnival workers. From that point on, Claremont starts focusing on his female characters, building his stories around them that challenge their place in this world, threatening them with power, knowledge, and even identity in stories about their place in a world that fears them. His stories are about Jean Grey, Ororo, Rogue, Kitty Pryde, Madelyne Pryor, Alison Blaire, and Elizabeth Braddock (and you could even throw in villains like Emma Frost and Mystique to this list) and what this life does to them, how it forges them and even how it twists them. And Inferno is all about the twisting of these characters. Wolverine, Colossus, and Nightcrawler hardly go through the emotional gauntlets that Claremont’s female characters do.

But his stories are also about the power, the grace, and the strength of these characters. Illyana Rasputin overcomes the demonic part of her soul to triumph. Jean regains a part of her that she wasn’t even aware was taken from her (just one part taken from so many parts that had been stolen from her.) And even Madelyne gets something, whether it’s peace or release or maybe even revenge. She gets a conclusion to her story- something that is hers and not just a mirror of Jean Grey’s life. That is what Claremont’s time guiding these books has done— given the women of this era the spotlight. He’s challenged them to look at the world outside of themselves in ways that the men just don’t or can’t. It’s not that he’s forced them to do it but he’s given them an agency and roles in his stories that are more than just the mother or the girlfriend.

Even with that, Madelyne ends up being the most tragic character because ultimately her agency sort of becomes just not being Jean Grey. That’s a role that was cast for her the moment the higher-ups at Marvel passed on the edict that Jean Grey needed to return to life. Out of that, there’s this “love” triangle between Madelyne, Jean, and Cyclops that leaves all three of them out of sorts for a couple of years. Madelyne is a character who’s had her purpose stripped from her, Cyclops uncharacteristically abandons his wife and newborn son, and Jean Grey is a homewrecker. Claremont and Simonson spend a couple of years before Inferno trying to make something out of all of that but Inferno finally addresses all of that head-on, turning everything that happened into some nefarious scheme of Mister Sinister.

Inferno almost reads like a thesis statement for Claremont’s run with the X-Men, his chance to tell the story of these mutants one more time hoping that this time you’ll see what he’s doing. It’s one of his more complicated and nuanced stories that operates on a broad canvas but his portions of this storyline try to bring all of these strands and themes that he’s been weaving since 1975 back together. And maybe that’s something that you only see on a massive rereading like this— how this large story stretches forward and backward through the years, picking up long-forgotten discussions with his readers that they had thought dropped ages ago. But Claremont never forgot them; he’s just been weaving other topics and points into the discussion that build upon everything that he’s been doing in Uncanny X-Men since he started writing the book.

Comments ()