My Claremont Year- February 2023

Days of Future Past establishes the story that Claremont told in Uncanny X-Men but it takes him a few years to realize that.

Around the end of 2022 a thought struck me; have I ever read all of Chris Claremont’s X-Men? I think I’ve collected it all in one form or another (or even multiple forms) but there’s a point in the mid-1980s where a lot of it becomes fuzzy in my memory. I probably read it when it was coming out but more out of the inertia of collecting than any love of it. So armed with several omnibuses, Marvel Unlimited, and whatever back issue diving I need to do, I’ve set the goal to read his 16-year run on X-Men, New Mutants, and other related books, probably also eventually including some Louise Simonson New Mutants and X-Factor here as well since the series are so tied together.

As much as this is to check out these stories again, I want to see if there’s a completeness to the story that Claremont was telling, starting with his first issue, X-Men #94 (1975), and extending all the way through X-Men #3 (1991). Maybe by the end of 2023, I’ll have some kind of grand unified theory of Chris Claremont’s time on the book or maybe I’ll just have read a lot of comics that range from “not bad” to “what were they thinking?”.

This month, we're covering 1980 to 1982, which is the heyday of Claremont's run on Uncanny X-Men.

- Uncanny X-Men #132- 166

- Uncanny X-Men Annual #4 & 5

- Spider-Woman #37 & 38

- Avengers Annual #10

- Marvel Team-Up #100

- Marvel Fanfare #1-4

- X-Men/The New Teen Titans

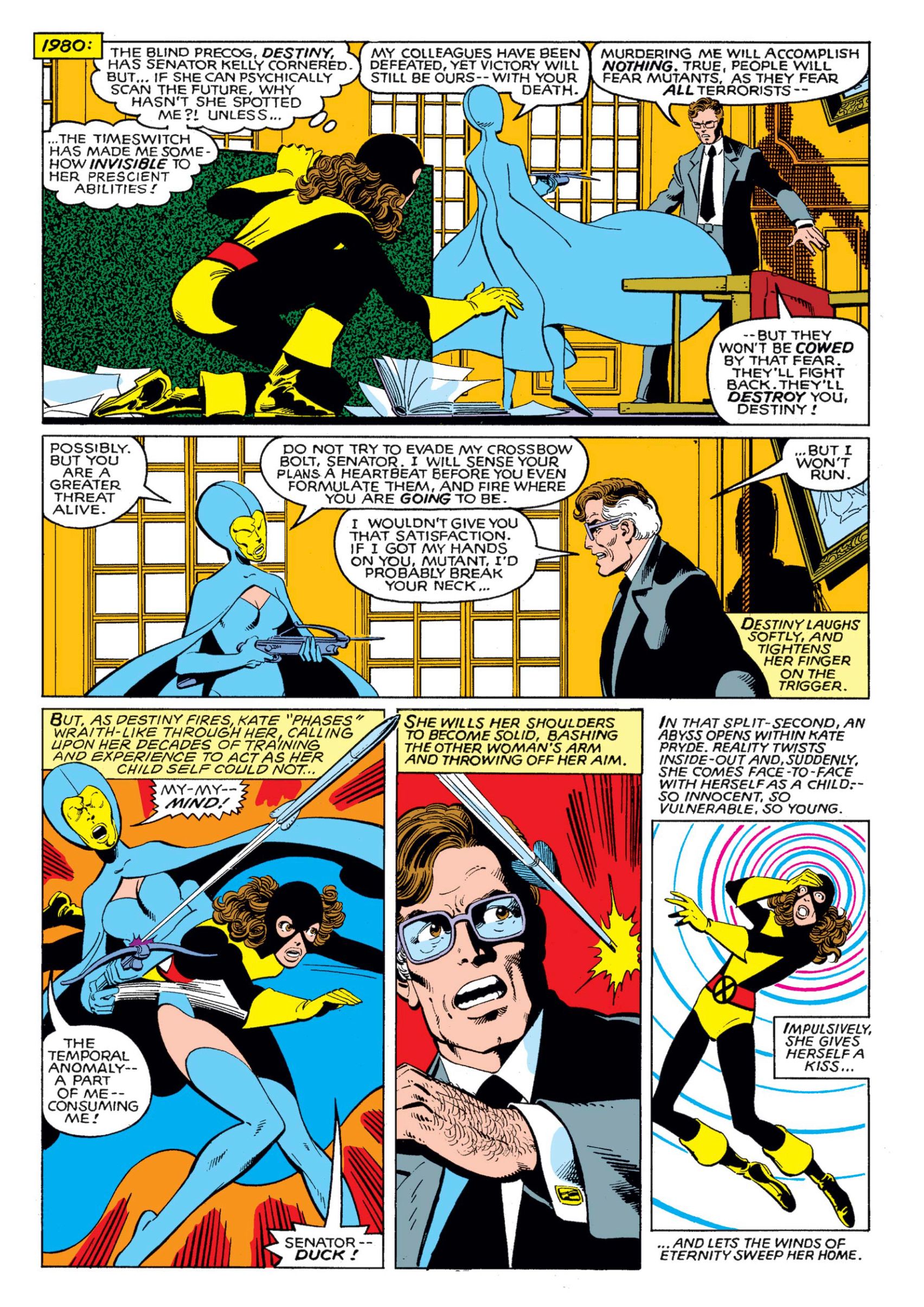

February started with the classic The Dark Phoenix Saga but on this rereading of these stories, it’s Uncanny X-Men #141 and 142, Days of Future Past, that stuck out to me. With just one fun Kitty Pryde issue left in #143, the two Days of Future Past issues are John Byrne and Terry Austin’s goodbye to the series that made them comic superstars but it’s also where Chris Claremont finally seems to figure out what his story of the X-Men actually is. His X-Men tale is a fight for the future. In those issues, a Kate Pryde from a dystopian future where mutants have either been killed or herded into mutant concentration camps sends her mind back to the present-day Kitty to help prevent events that are key to ensuring that her awful future will come to pass.

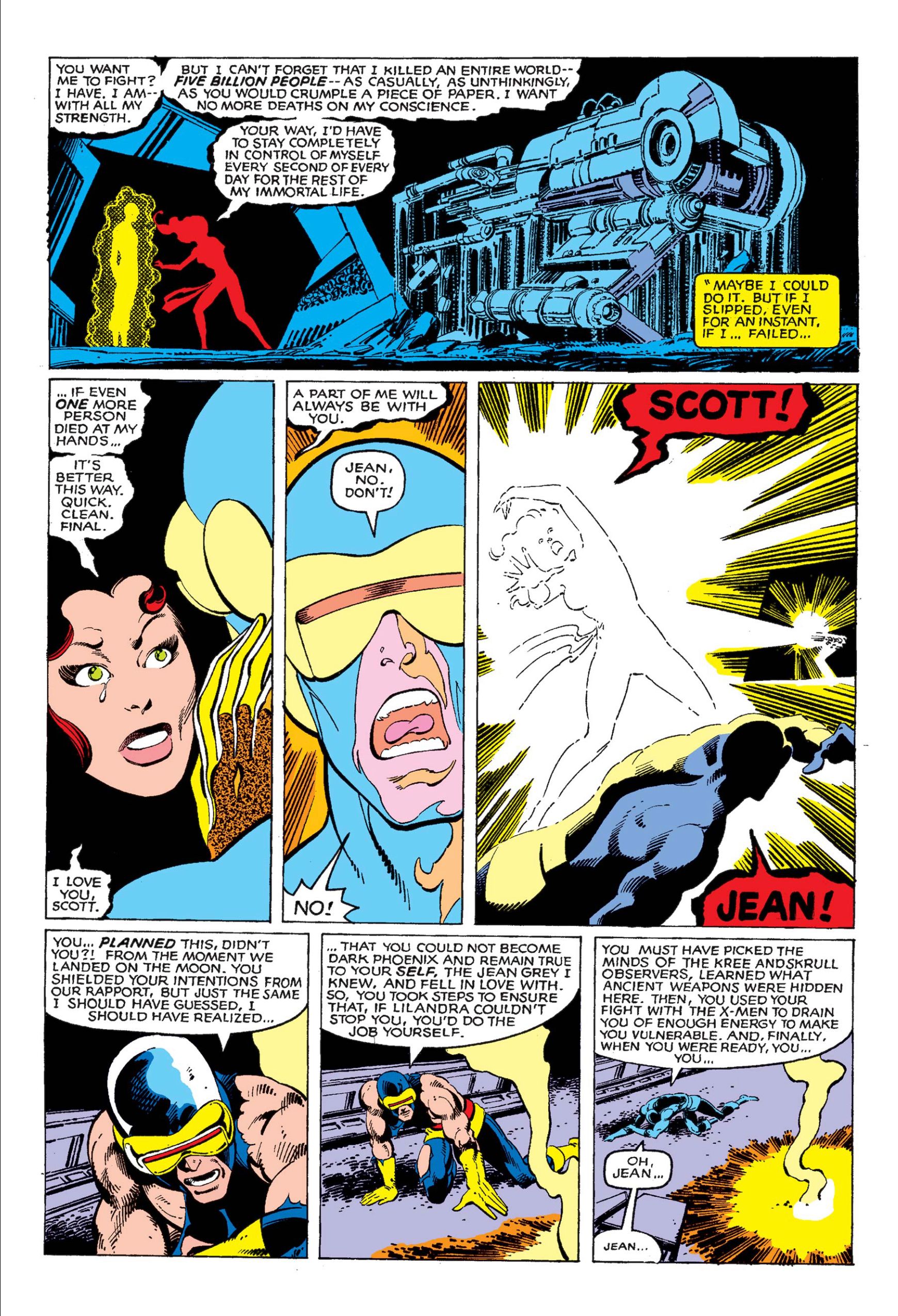

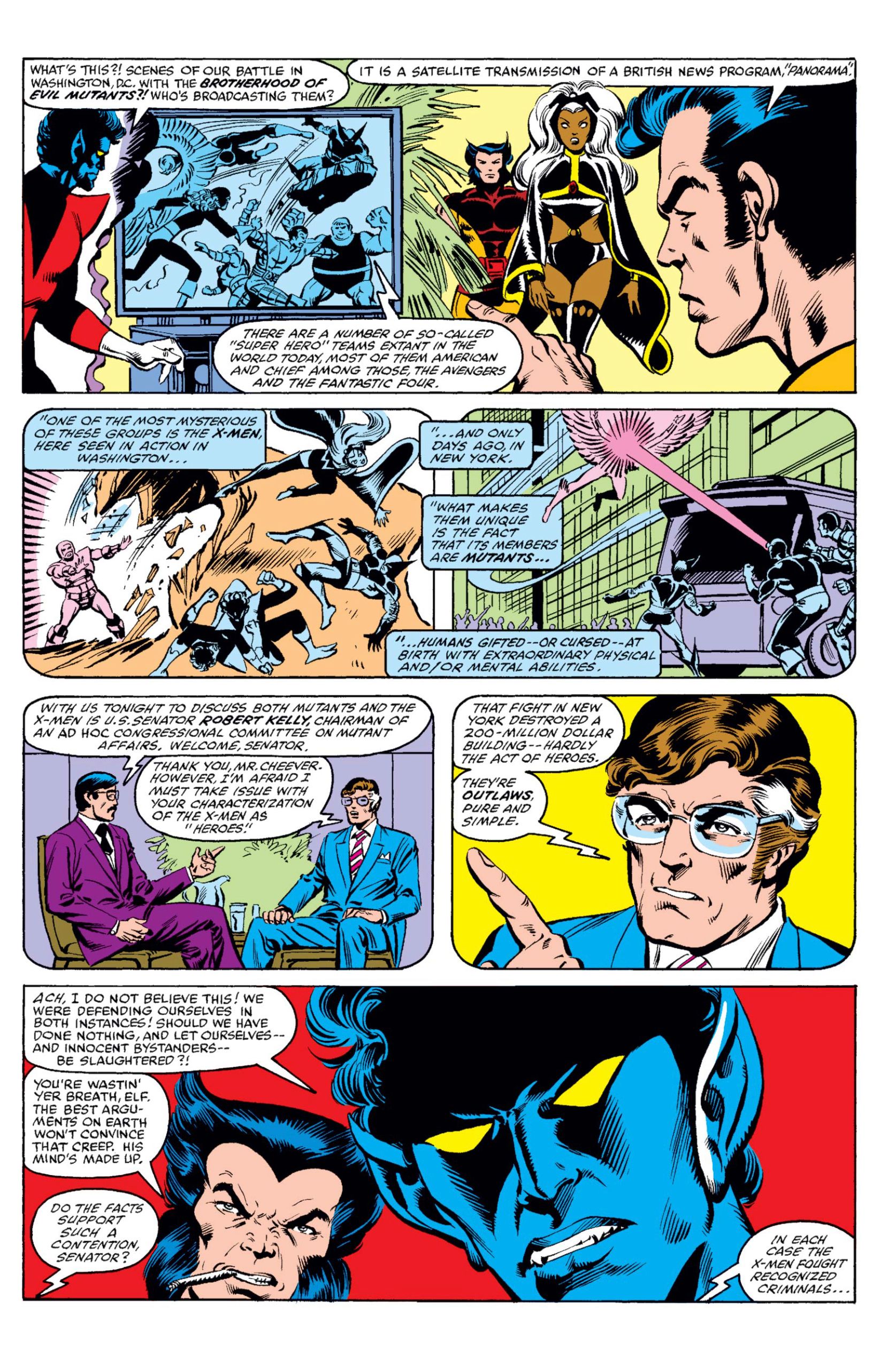

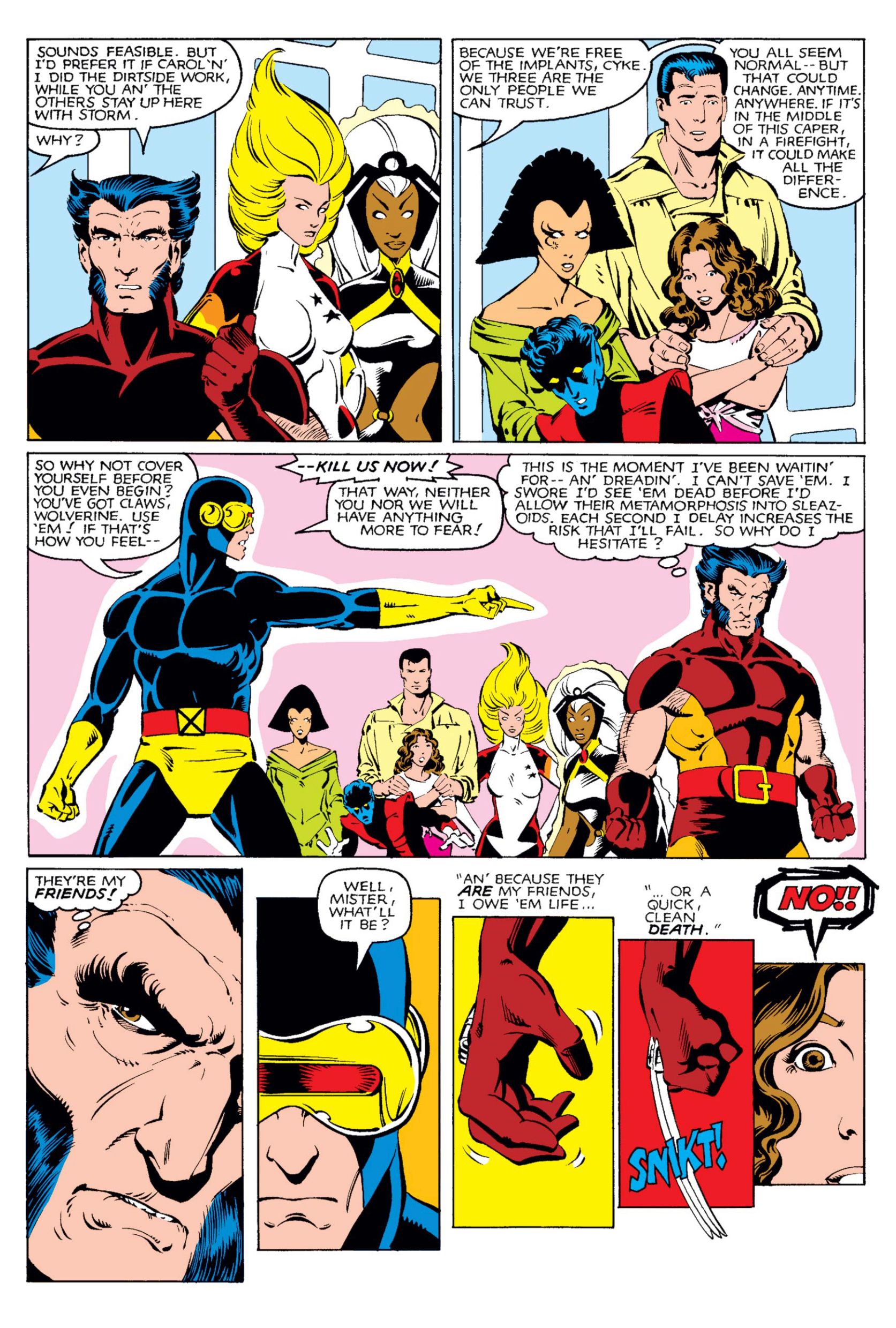

While he’s dropped hints at the possibility before this, these issues are really where Claremont develops the idea of the X-Men as persecuted outlaws. The Dark Phoenix Saga is the showier, louder version of this, with the X-Men attacking the Hellfire Club in their swanky party, which was attended by anyone who was anyone at the time. It was a public outing of the dangers of mutants for the whole world to see. But before he follows up on the image hit that the X-Men take, Claremont has to conclude the story of Jean Grey, the Phoenix. The closing of Jean’s story is a closing on the innocence and childhood of this team. Wolverine, Colossus, Storm, Nightcrawler, Cyclops, and Professor Xavier have to fight for the life of a teammate and a loved one when it’s questionable whether Phoenix deserves that kind of loyalty.

Sure, X-Men have died before, most recently John Proudstar, Thunderbird, in Claremont’s second issue but that was due to the creative limits of Claremont at that time, unable to see why a team needed both Thunderbird and Wolverine, so one of them had to go. But in those few issues that Thunderbird appeared in, there was no time to get to know him, to grow attached to him, or to mourn him when he was killed. He died for his team. That death was probably the biggest character moment for him.

But Jean was different; she was a founding X-Men. Claremont, Cockrum, and Byrne obviously loved her; in the original version of The Dark Phoenix Saga, Jean lived after the Phoenix power was exorcized from her. And then Jim “every issue is someone’s first issue” Shooter stepped in and set down his Editor-In-Chief edict that Jean Grey needed to die for her actions as Phoenix. The Dark Phoenix Saga is a big, epic story, the longest that Claremont had written up to that point. In a lot of ways, it’s everything that an X-Men book should be; it’s a classic that still holds up today if you can find your way through all of the words that Claremont puts on every page. It’s worth the read.

So Days of Future Past is almost a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it story with only two issues but it lays down the foundation for almost every X-Men story that follows it. It firmly establishes the “hated and feared” portion of the X-Men myths while emphasizing the two choices for mutants— the X-Men path of working towards a peaceful future or the Brotherhood of Evil Mutants’ path of ensuring a future for the mutants alone. Every instance of a law being passed against mutants or every possible future suggested after this can all be traced back to the events of this two-part story.

And that goes through the present day. Jonathan Hickman’s House of X/Powers of X era of stories is another one of those possible future stories; it’s just that we’ve caught up with that future. Imagine if the Kate Pryde of the Krakoa era psychically jumped back into her 13-year-old body and told or warned the X-Men what they would become and do. What would Claremont’s X-Men think of Hickman’s X-Men?

So after the powerful one-two punch of The Dark Phoenix Saga and Days of Future Past, it’s weird how Uncanny X-Men settles into a fairly safe status for a few years. When Byrne leaves, Dave Cockrum returns. The X-Men fight Doctor Doom and Arcade. Claremont starts setting up a space opera with the return of the Starjammers but after the tumultuous time of the end of the Byrne era, the Cockrum stuff feels kind of tame following it up. Now Cockrum was a great artist and it showed how much he loved these characters and Claremont’s stories but between Byrne and Paul Smith (and all of the artists that followed Smith,) Cockrum’s second run on Uncanny X-Men doesn’t have the ferocity that his first run did. Maybe it’s the inkers but Cockrum’s art in the first run feels raw, creative, and unrestrained. When he returns, he’s coming back to a top-selling comic and his artwork feels like it’s trying to maintain something instead of pushing what he’s capable of.

He’s not helped much by Claremont’s writing either. If Days of Future Past unlocked something in him, Claremont appears hesitant to follow it up immediately. He’s still early in his run and wrapped up a big story with Jean Grey’s death but has so much more ahead of him. This period of Uncanny X-Men pulls back on Claremont trying to tell grand stories and instead sees him trying to tell X-Men stories. He’s established what those stories are and now he has to live up to the expectations he’s set for what an issue of X-Men should be.

But we get to see some experimentation poking through here, whether it’s the four issues of Marvel Fanfare, drawn by Michael Golden, Dave Cockrum, and Paul Smith, where Claremont gets to return to the Savage Land, a setting he always seems to enjoy, or artistic fill-ins by Brent Anderson and Bill Sienkiewicz, two artists who are from a completely different mold than Cockrum. With these artists, Claremont realizes that X-Men stories can be so much more than just what they’ve been. Look at Brent Anderson’s issue, an exploration of the mysterious island that the X-Men briefly called home and setting up Illyana Rasputin’s story. Like Days of Future Past, this issue sets up another possible future for the X-Men, completely different from that dystopia but no less threatening. The future threat facing the X-Men after this issue isn’t political but mystical. It shows the richness of the stories that Claremont is building. This issue shows that the X-Men aren’t just stuck fighting other mutants or being hated and feared.

This second month of rereading Claremont’s X-Men stories starts with such promise with both The Dark Phoenix Saga and Days of Future Past but after Byrne leaves, Claremont spends a few years churning out good but ultimately unremarkable stories. This is the safe period of his run; the team is established so let’s tell stories about The X-Men. Nothing wrong with that. But then the last two issues introduce Paul Smith as the new regular artist on the series, taking over from Cockrum before the ending of a big space epic. Smith introduces a lithe line to the series, a thin, purposeful one that was able to show who these characters were better than Cockrum’s rather blunt lines. There’s a depth of personality behind Smith’s figures that make this space ending, where the X-Men are quite literally fighting for their souls epic and personal at the same time. It’s a jolt that this series needed.

Next month: God Loves, Man Kills and The New Mutants

Comments ()