My Claremont Year- The End

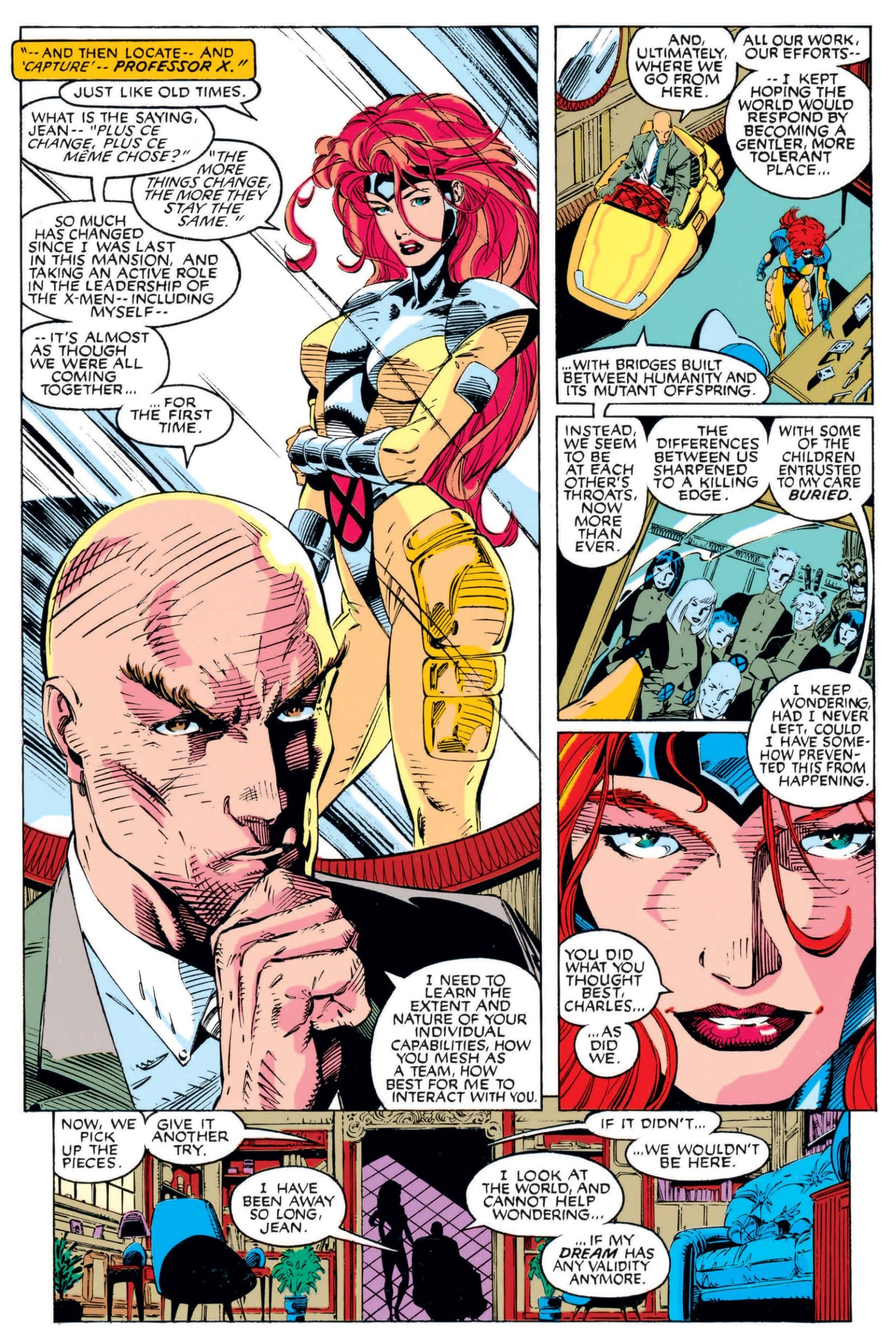

Chris Claremont’s X-Men were rarely about the costumes or their super-heroics

I spent 2023 reading Chris Claremont’s Uncanny X-Men run. It started when I was six years old, but I probably didn’t find it until I was closer to ten or eleven, and ended when I was 21. That alone probably explains my fascination with this book, these stories, these characters, and this writer. But I don’t know if I ever really thought about the book or revisited it. Did I just have rosy memories of the comic because I was young and didn’t know better or was Chris Claremont that good?

And the answer is that he actually was pretty good.

While it’s a bit later than I wanted, here’s my final post (for now maybe) about Chris Claremont’s X-Men run, and the ups and downs of it.

And for those of you catching up, here are the previous installments of “My Claremont Year,” highlighting the issues I read for each installment:

- Uncanny X-Men #94-128 (Second Genesis)

- Uncanny X-Men #132-166 (The Dark Phoenix Saga)

- Uncanny X-Men #167-188 (God Loves/Man Kills)

- Uncanny X-Men #189-209 (Cyclops Versus Storm)

- Uncanny X-Men #210-227 (Fall of the Mutants)

- Uncanny X-Men #228-243 (Inferno)

And for this final installment, here are all of the comics that I read at the end of 2023:

- Uncanny X-Men #244- 280

- Uncanny X-Men Annual #14 & 15

- X-Men #1-3

- Excalibur #8-34

- Excalibur: Mojo Mayhem

- Wolverine #1-10

- New Mutants #81

- X-Factor #64-70

And now, let’s look at the end of Chris Claremont’s time with the X-Men.

“The end of our elaborate plans

The end of everything that stands”

The Doors, “The End”

Chris Claremont’s 15-year run on The X-Men ends with neither a bang nor a whimper. It just kind of ends. And that’s no small feat when the ending started with the biggest-selling comic of all time– 1991’s X-Men #1, which reportedly sold over 8 million copies. Claremont’s last two years, following Inferno, feel a lot like they’re marking time as Claremont dismantles the team after the crossover, scattering them all across the globe. Most of these two years are then spent following each member into a new life; Storm is regressed to being a young girl, Dazzler ends up famous in Hollywood, Colossus gets to live as an artist in NYC, Havoc becomes a soldier in Genosha, and Wolverine ends up in the far east, nearly dying as his powers fail while he tries to rescue Psylocke and reassemble the team. Claremont is trying to do his version of super-hero deconstruction like Alan Moore and Frank Miller were doing over in Watchmen and The Dark Knight but he just doesn’t have the cynical streak in him that Moore and Miller did. He didn’t see the darker side of his heroes so his take on deconstruction was quite literally deconstructing the team and putting them back together as they were, a few pieces moved around or introduced but that’s basically what he had been doing with this team since 1975.

While he was doing this, it felt like Claremont was lining up all of the pieces for one last big hurrah, a showdown with the Shadow King. The Shadow King had been introduced back during John Byrne’s run on Uncanny X-Men, in a flashback issue that showed the first showdown between Charles Xavier and the Shadow King. It was practically a one-and-done battle, something to provide some insight into Xavier’s past before Byrne and Claremont dove into a bit before the heart of their run, The Dark Phoenix Saga. The Shadow King was truly Xavier’s opposite, even more than Magneto, but was a one-and-done villain. At least Xavier and Magneto shared a goal in the safety of mutants even if they came at it from opposite directions. In The Shadow King, Xavier had an adversary who didn’t care about anything other than himself. The Shadow King would eventually show up again in The New Mutants before Claremont’s Asgardian Wars but following Inferno, the Shadow King became the background puppet master of the X-Men, manipulating them and their allies as he gained power.

This could have been Claremont’s big story, one final grand statement about Marvel’s X-Men but before he could get into this X-Men/X-Factor crossover that would see them go up against the Shadow King, he was replaced on Uncanny X-Men for two issues by Fabian Nicieza and the whole story, the defeat of the Shadow King and the reunification of the X-Men and X-Factor into one team just limped along to an ending, barely registering as anything as Chris Claremont’s run on Uncanny X-Men came to a close. One month, Chris Claremont was writing Uncanny X-Men and the next month he wasn’t.

And then came X-Men #1 by Chris Claremont and Jim Lee, still the biggest-selling comic book of all time.

During the previous two years, Jim Lee had been one of the artistic voices on Uncanny X-Men, doing a handful of issues here and there, alternating with the likes of Marc Silvestri, Bill Jaska, Rick Leonardo, and Mike Collins. Lee was a throwback to the Byrne/Austin days of the book, establishing a new pre-Image Comics coolness in his artwork. With Lee, Claremont’s stories had an energy to them that was missing from a lot of the other artists (sorry, Jaska and Collins, but it’s true) and is maybe the artistic saving grace of Extinction Agenda, a visual and narrative hodgepodge of artists (who thought pairing Jon Bogdanove and Al Milgrom was a good idea?). Lee shines in the storylines after that which sees a newly reformed X-Men team kidnapped to space to save the Shi'ar empire from Charles Xavier. Claremont seemed to be embracing the exciting tone that Jim Lee brought to his stories so a relaunched title should have been a wonderful sign of what was to come.

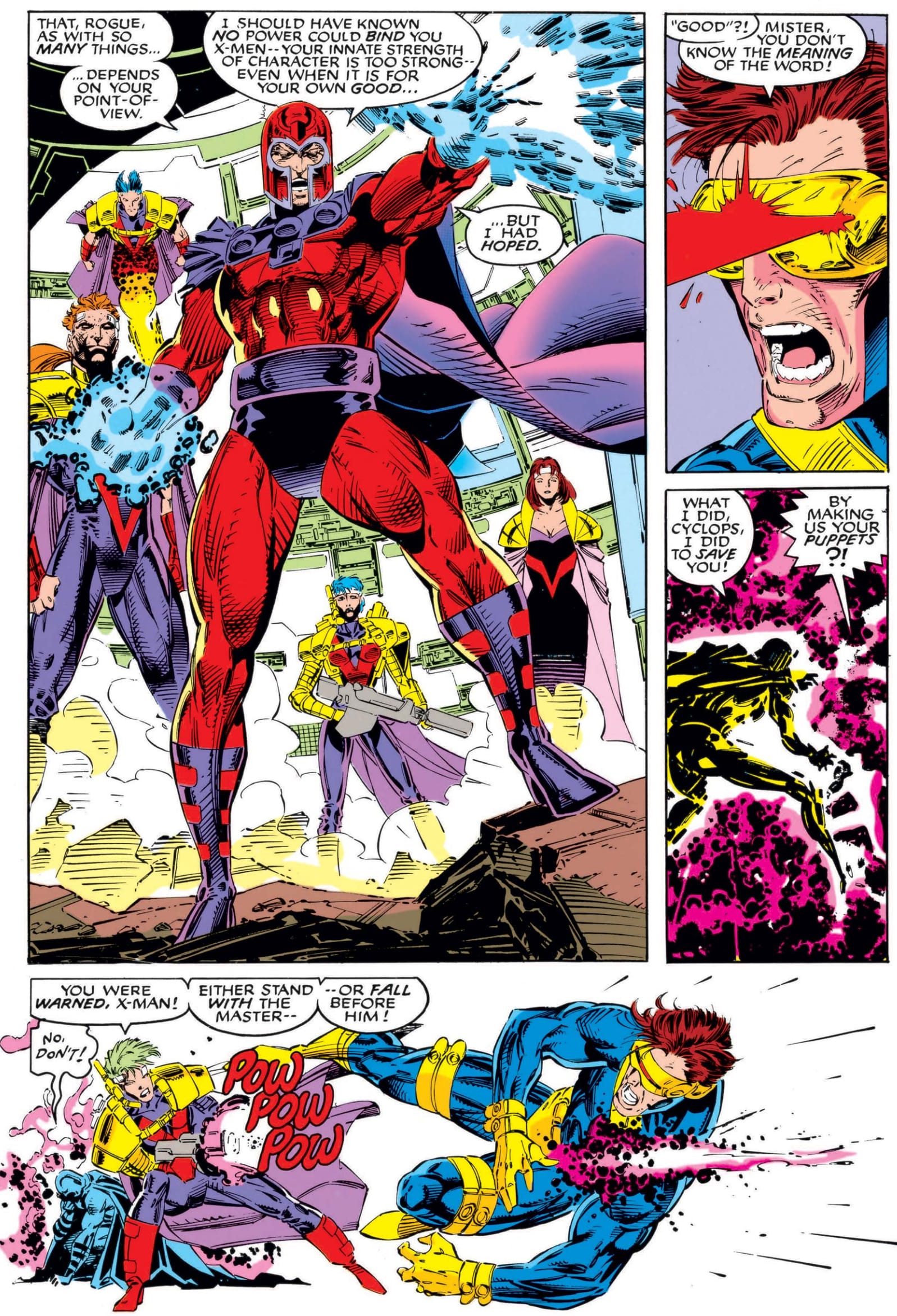

X-Men #1 brings together the original X-Men team as well as a revamped Uncanny-era team into one team, which they would then split into an X-Men Gold and X-Men Blue team. This issue kicks off another battle with Magneto, now apparently a villain again after having been an X-Men ally for several years. Claremont’s goodbye to The X-Men is basically a resetting to some kind of status quo that never really existed, where the X-Men were a team of superheroes that operated in a mansion somewhere outside of New York City. And that almost sounds like what the team under Claremont largely was but it also ignores almost everything that Claremont tried to make this book be, how he tried to subvert the idea of the X-Men as heroes to make them human instead.

Claremont’s X-Men were rarely about the costumes or their superheroics. Looking over his fifteen-year run, the costumes were just a facade for these characters; the action was the setting for Scott, Jean, Logan, Ororo, Kurt, Peter, Kitty, and Rogue to act against. If Claremont was just writing superhero stories, the (first) death of Jean Grey wouldn’t be so painful or Ororo’s search for meaning when she lost her powers wouldn’t have been as engaging. Logan became the breakout character of this run and was pegged as the “kewl” character but Claremont wrote him as a person trapped between the man he was and the man he knew he could be. These characters weren’t just secret identities, incredible powers, and colorful costumes. His 15-year story (that crossed over into New Mutants, Wolverine, and Excalibur) lived and breathed in ways that few comics did at the time or have been able to since, including nearly every other version of X-Men books since.

“What’s the saying, Jean- ‘plus ce change, plus ce meme chose?’” Xavier asks Jean Grey in X-Men #1. “The more things change, the more they stay the same,” Jean conveniently translates for the non-French readers among us. X-Men #1 both acknowledges everything that has happened in the past 16 years, including the reformation of Magneto, and then tosses it all out the window, as if resetting everything to 1963’s X-Men #1. For one reason or another (and that reason’s name is often hypothesized to be Jim Lee) X-Men #1-3 offers retrograde storytelling, resetting this franchise (and that’s what it is at this point) back to some imaginary point in time when all mutants lived happily together at Xavier’s School For Gifted Youngsters.

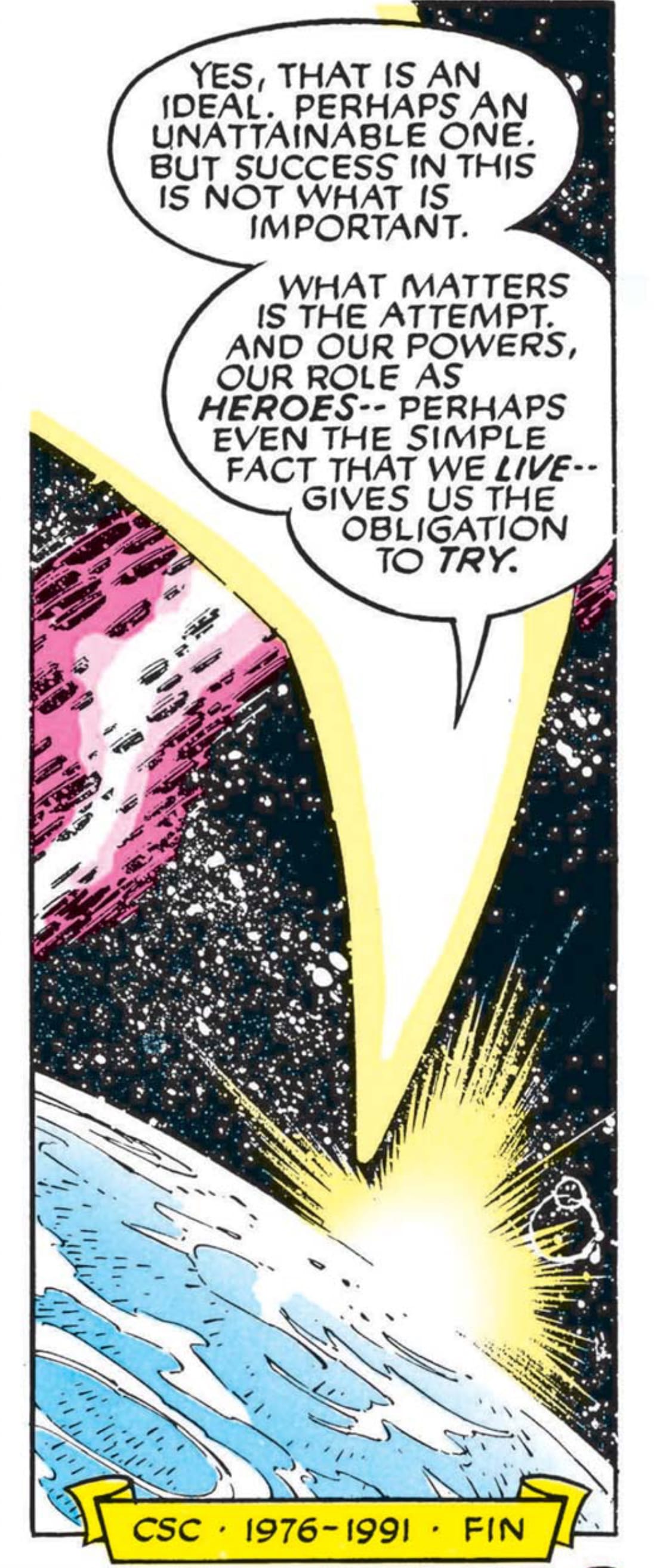

The biggest-selling X-Men comic of all time doesn’t celebrate all the accomplishments of Claremont; it tears them down to enter the 1990s and begin a phase of corporate-produced books with journeymen writers and artists picking up the reins to carry us into the hologram and foil cover era of comics. X-Men #3 ends with one final and small caption on the last panel of the issue— “CSC- 1976-1991- FIN”— reading more like a headstone message than a writer signing off from a historic run on the comic.

And that’s a disappointing ending to such a great run of comics. Kind of like how people learned the wrong lessons from Alan Moore, the writers and artists who came after Claremont learned the wrong lessons from him. They saw the surface of what he was doing and thought that was what was great about X-Men comics. And mostly that equated to Wolverine was cool and everything else was all surface-level faking it until they made it. It’s not like Claremont had to leave behind a map for anyone to follow; his work speaks for itself. Reading his work all these years later, he was always moving forward, trying to follow the characters where they lead, letting them have their lives. Once he left, the X-Men calcified, trapped in some idea of what they were for now and forever. Claremont wasn’t trapped by a legacy that he needed to sustain; he was telling stories with no expectations of what they should be. And that led him, his readers, and his characters down so many great and unexpected paths.

Comments ()