My Claremont Year- May/June 2023

Chris Claremont starts setting up for the X-Men’s future, starting by removing links to their past.

Around the end of 2022 a thought struck me; have I ever read all of Chris Claremont’s X-Men? I think I’ve collected it all in one form or another (or even multiple forms) but there’s a point in the mid-1980s where a lot of it becomes fuzzy in my memory. I probably read it when it was coming out but more out of the inertia of collecting than any love of it. So armed with several omnibuses, Marvel Unlimited, and whatever back issue diving I need to do, I’ve set the goal to read his 16-year run on X-Men, New Mutants, and other related books, probably also eventually including some Louise Simonson New Mutants and X-Factor here as well since the series are so tied together.

As much as this is to check out these stories again, I want to see if there’s a completeness to the story that Claremont was telling, starting with his first issue, X-Men #94 (1975), and extending all the way through X-Men #3 (1991). Maybe by the end of 2023, I’ll have some kind of grand unified theory of Chris Claremont’s time on the book or maybe I’ll just have read a lot of comics that range from “not bad” to “what were they thinking?”.

This month, we're covering 1984 to 1986, a bridging period in Uncanny X-Men be coming.

- Uncanny X-Men #189- 209

- New Mutants #22-44

- Uncanny X-Men Annual #8, 9, & 10

- X-Men /Alpha Flight #1 & 2

- Marvel Fanfare #40

- New Mutants Special #1

- New Mutant Annual #2

- Nightcrawler #1-4

- Power Pack #40

- Web of Spider-Man Annual #2

- Longshot #1-6

Before we begin, it was The Claremont Run on Twitter that really sparked my interest in revisiting Claremont's X-Men. For the last couple of years, that account was daily exploring aspects of Claremont's run, mostly diving into Claremont's own work regarding characters, identity, and gender. It really dove into the 16-year run and peeled back the richness of the text.

Two weeks ago, project lead J. Andrew Deman announced that The Claremont Run is now going to be a book published later this year from University of Texas Press.

A data-driven deep dive into a legendary comics author’s subversion of gender norms within the bestselling comic of its time.

By the time Chris Claremont’s run as author of Uncanny X-Men ended in 1991, he had changed comic books forever. During his sixteen years writing the series, Claremont revitalized a franchise on the verge of collapse, shaping the X-Men who appear in today’s Hollywood blockbusters. But, more than that, he told a new kind of story, using his growing platform to articulate transgressive ideas about gender nonconformity, toxic masculinity, and female empowerment.

J. Andrew Deman’s investigation pairs close reading and quantitative analysis to examine gender representation, content, characters, and story structure. The Claremont Run compares several hundred issues of Uncanny X-Men with a thousand other Marvel comics to provide a comprehensive account of Claremont’s sophisticated and progressive gender politics. Claremont’s X-Men upended gender norms: where female characters historically served as mere eye candy, Claremont’s had leading roles and complex, evolving personalities. Perhaps more surprisingly, his male superheroes defied and complicated standards of masculinity. Groundbreaking in their time, Claremont’s comics challenged readers to see the real world differently and transformed pop culture in the process.

I'm looking forward to checking this out when I'm close to the end of my time with these books.

And now, onto your regularly scheduled programming:

So I think I’m somewhere around halfway through my reread of Claremont, give or take a year or two, having read over 100 issues of Claremont’s X-Men run and most of his New Mutants run (there’s only about a half year left to go of New Mutants after this.). The next major storyline to get into after these issues is the “Mutant Massacre” arc, where the X-Men get pulled into a cycle of crossovers (Mutant Massacre, Fall of the Mutants, Inferno, Days of Future Present, X-Tinction Agenda, and Muir Island Saga) that define and shape Claremont’s remaining years chronicling Marvel’s mutants. These issues of Uncanny X-Men, covering #189 to #209 feel like a transition point for Claremont.

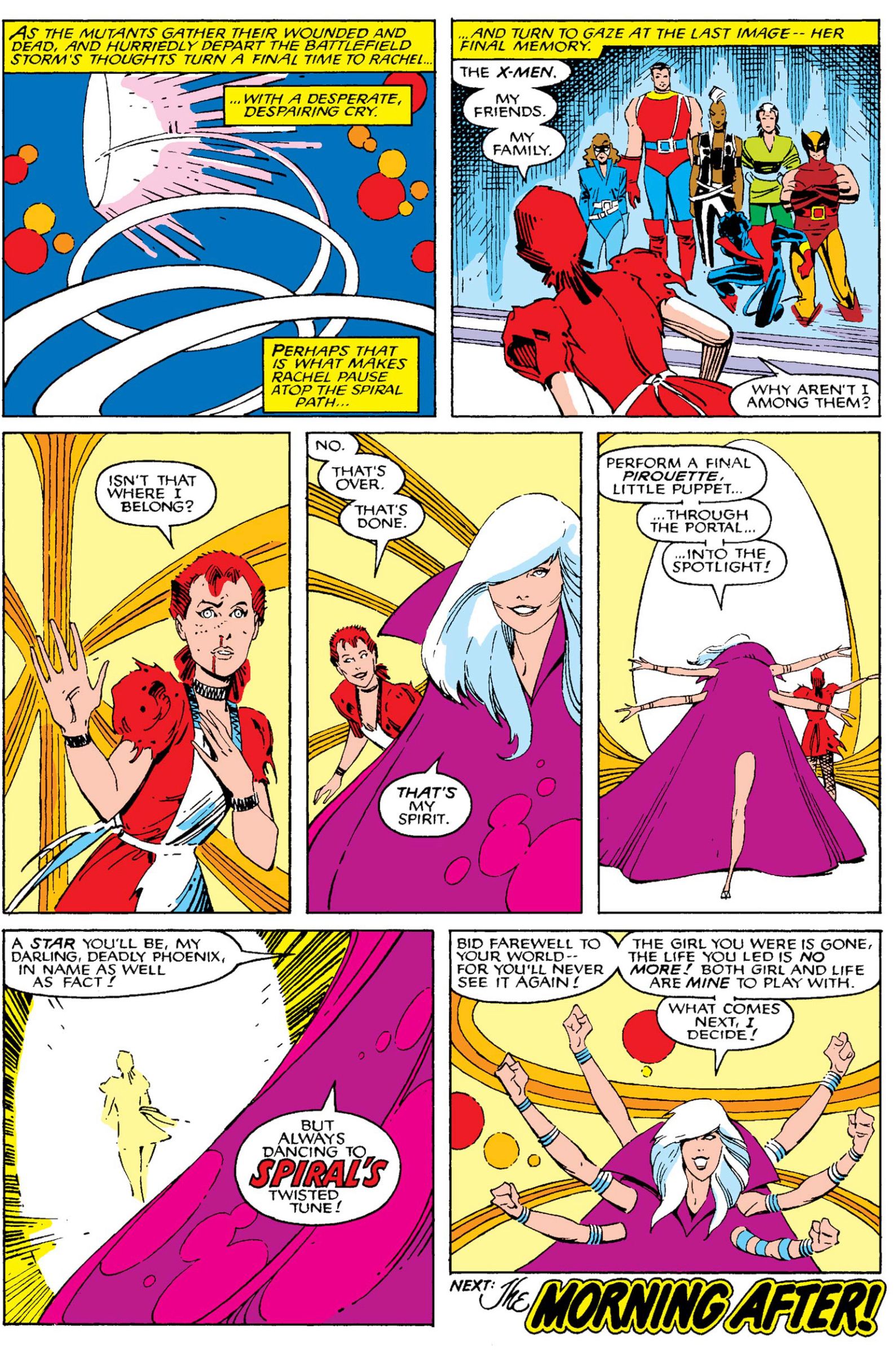

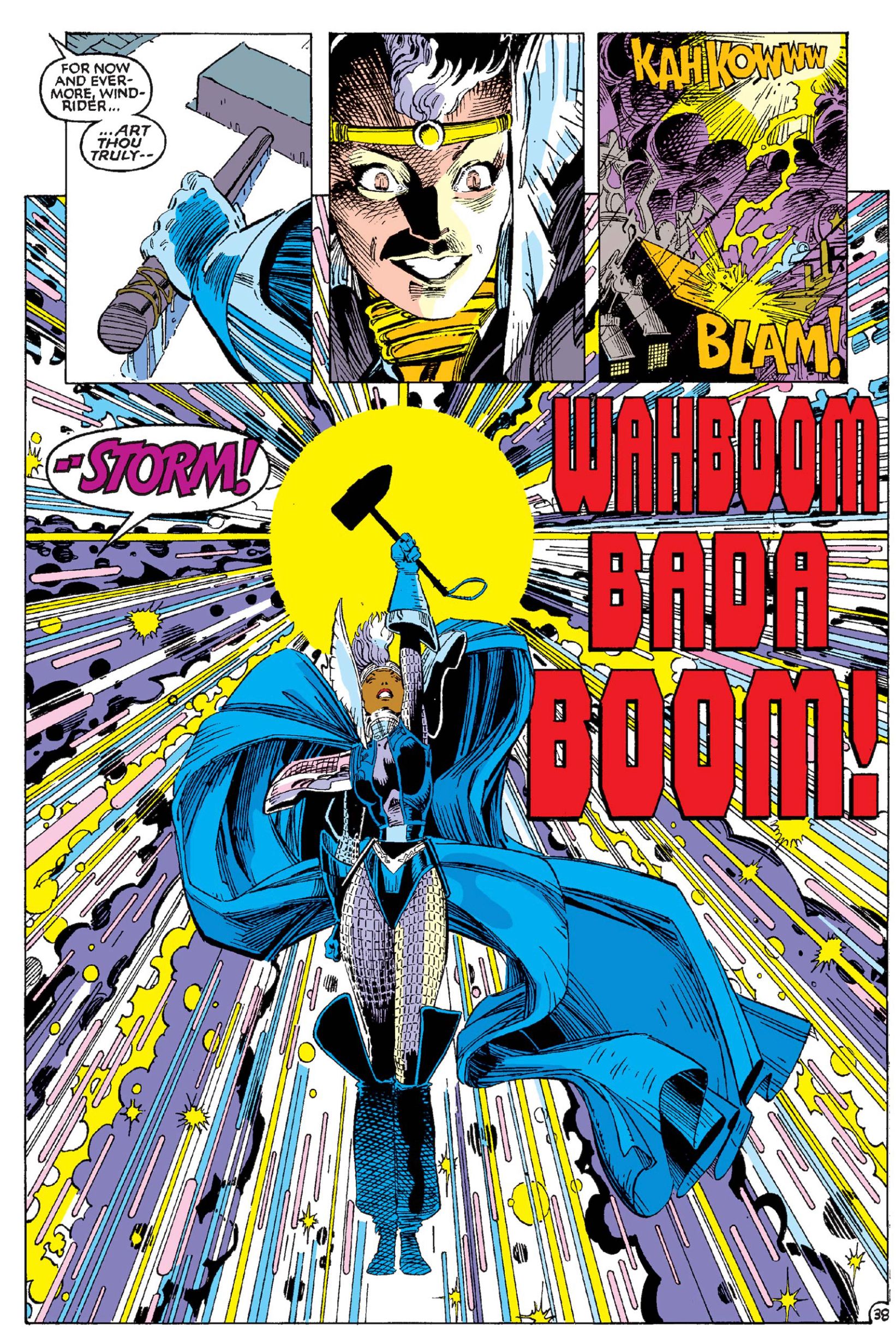

By this time, Uncanny X-Men has become a big success for Marvel. Claremont has seen these characters go from newcomers that no one knew to be the most popular book thing on the comic racks so Claremont starts to see just how far he can push this book before Marvel and Jim Shooter try to take it over. Storm has been robbed of her powers, Rogue is still a bit of a wild card on the team, and over in New Mutants, Claremont starts to follow some narrative trails that he planted early in that title’s run. There’s a strong feeling in these issues that something is coming. The strong presence of Rachel Summers in these issues, reintroducing her in the current timeline from the “Days of Future Past” storyline suggests that the future isn’t quite as written in stone as we thought and that anything could happen.

The daughter of Scott Summers and Jean Grey from an alternate future timeline, Rachel’s story is a reminder of the fate that “Days of Future Past” showed us— mutants dead or collected into concentration camps, constantly guarded by Sentinels— while her appearance in the X-Men’s present is already a change to that established timeline. Future X-Men writers would use the idea of a dystopian future to tell all kinds of far-out and disconnected stories but Claremont uses Rachel as an agent of disruption. She’s a woman out of time, from a time that probably doesn’t exist anymore. Her mother is dead before she ever gave birth; her father is married to another woman who’s pregnant with Cyclop’s son. Rachel shouldn’t exist. She’s the impossible girl living an impossible life.

With this disruption, Claremont uses this time to mess around a bit with what and who we think the X-Men are. As if one troubled telepath/telekinetic running around wasn’t enough, Charles Xavier finds out that he has a son with reality-altering powers and multiple personalities. David Haller’s story (NM #26-28) plays out in the pages of the junior team, having the New Mutants confront facts about their mentor that the X-Men haven’t had to. In Uncanny X-Men, Xavier is the wise mentor and teacher. But over time, the X-Men became more his equals than his students. Storm and Wolverine have learned all that they can from him but for the New Mutants, they’re still the students but they get to witness Xavier’s failings in ways that the X-Men never did.

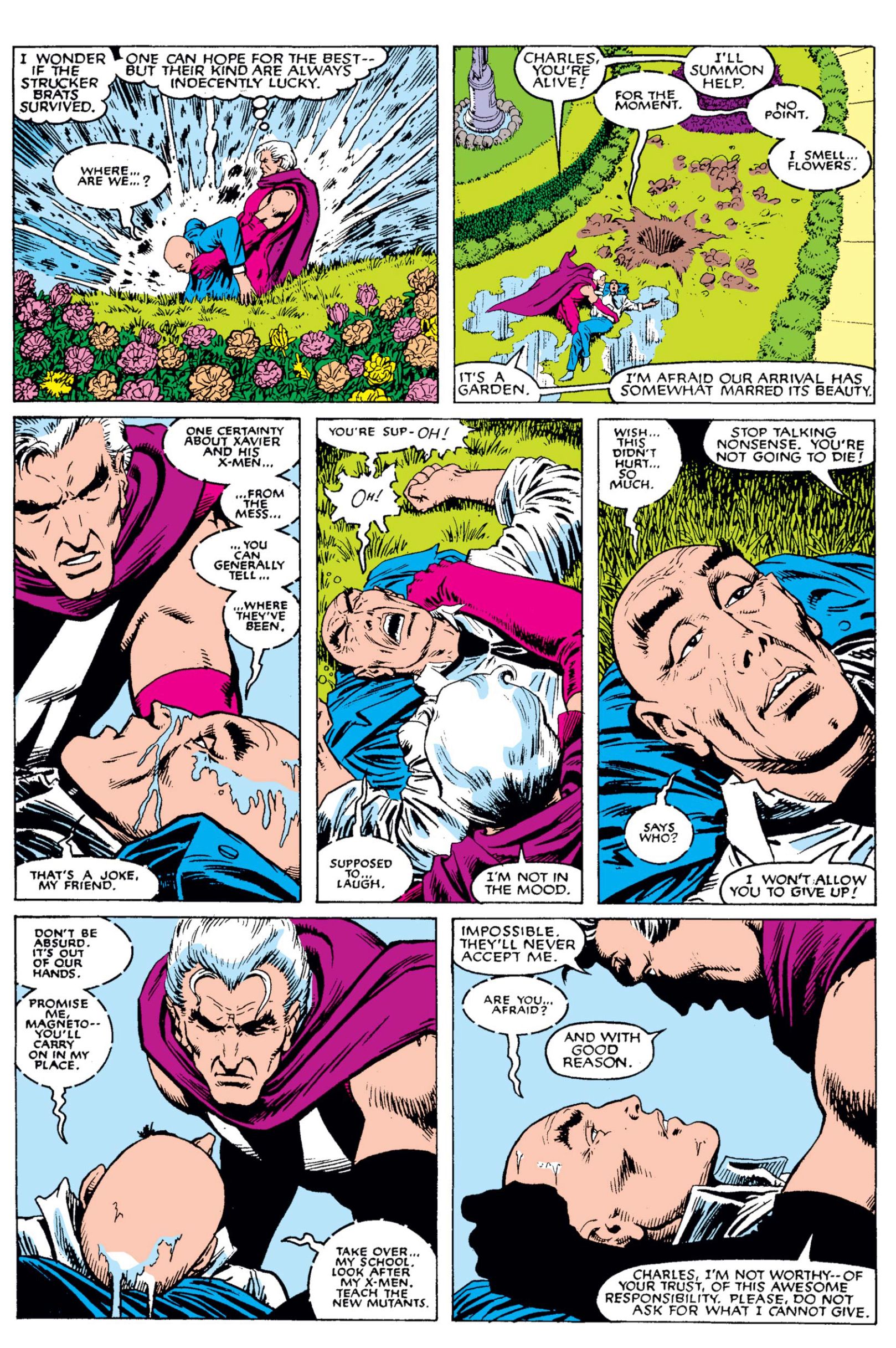

Xavier is on interesting ground in this period, dealing with rebellious teenage students while also having to adjust to the fact his older compatriots don’t need him in that way anymore. He and Storm butt heads over who should lead the team after he regains the use of his legs. He wants to be out in the field but doesn’t have the experience that the X-Men have. He’s trying to protect these teenagers, to teach them, but more often than not, he falls short. This is probably the most human time we see for Xavier; he isn’t the holier-than-thou leader of the X-Men. He’s a man who is forced to recognize that’s all he is; he’s no saint. And then when it comes to the point where he has to leave this world in Uncanny X-Men #200, he appoints the X-Men’s deadliest enemy Magneto to take his position and run the school.

The other longtime X-Man that Claremont removes from his story at this point is Cyclops. Since the death of Jean Grey, Cyclops has left the team multiple times but somehow or another, he’s always pulled back in. So Storm has had to deal with two men who are used to leading the X-Men, Scott Summers and Charles Xavier. Xavier gets critically wounded and can only find the necessary healing in space with his beloved Lilandra. For Storm, that’s one down. But with Scott, Claremont had spent a couple of years showing him and Storm getting in each other’s and the X-Men’s way when it came down to who was leading this team. Cyclops just assumed that he was Xavier’s anointed one because he always was but over time, Claremont wrote Storm and showed that she had earned the right to lead this team. Cyclops was given the team but Storm made it her team.

These are two characters that Claremont had struggled with throughout the first 10 years of his run because they tied the X-Men to their past, to the Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, and Roy Thomas days of the team. This is something that Marvel obviously wanted at this point, having turned The Defenders into some kind of X-Men West team with Angel, Beast, and Iceman over there leading that team. Bringing Rachel into the X-Men, having her take her mother’s place as Phoenix feels like a way forward but only works as long as Jean Grey remains dead, which only lasted so long and led to the launch of X-Factor, the original X-Men posing as mutant bounty hunters. But that feels like a story for another day.

Interestingly at this time, Claremont writes The Asgardian War epic. Over four issues (X-Men/Alpha Flight, New Mutants Special #1, and Uncanny X-Men Annual #9,) Claremont spins this story about all of the mutants fighting for survival on Asgard, Thor’s mythical home. The story pits the X-Men and New Mutants against Loki, who offers everything to the mutants at the cost of their own freedom. The story is probably most memorable for Art Adam’s artwork in the final two chapters but in the midst of all of these tight and personal stories that Claremont is working on, really putting his characters through the emotional ringers, he shows he can still do the big and epic stories. A few years later and this would probably have been a huge crossover event, with most Marvel comics tying into it one way or another, but before he disrupts everything in Uncanny X-Men #200, where Xavier leaves for (almost) good, Claremont gets to write a story showing that his characters can stand up to gods.

By Uncanny X-Men #209, Claremont has what’s his team- Storm, Wolverine, Rogue, Nightcrawler, Shadowcat, & Colossus. Even Magneto is a member by this point as Claremont has reformed the villain into a dubious replacement for Xavier. This introduces some good character conflict in Uncanny X-Men and New Mutants as this is a role that Magneto was never built for. It puts Magneto in a different situation, having to be a protector of more than just his narrow vision of what the world should be. Since at least UXM #150, Claremont had been pushing the character to be more than just a mustache-twirling villain but not every character is built to be a pure hero.

These issues around UXM #200, mark a bridge for the title and Claremont’s run of the book. These are some of the last issues for some time to feature such staples as Xavier’s School for Gifted Youngsters, the SR-71, or even the more cosmic aspects that have been part of the book up to this point. Claremont dismantles these ties to the past to push into the future. And he’s been on the book for 10 years at this point so it makes sense that he would have to do something to keep himself engaged and going on to redefine the status quo would be the best way to do it.

Comments ()