From Cover to Cover’s Favorite Comics of 2023

James, Mike and Scott take a look at our favorite comics of 2023.

It's time to engage in that year-end/year-beginning practice of looking back at some of our favorite comics of 2023. Let's just dive right into our favorite comics of the past year, presented to you in stunning alphabetical order!

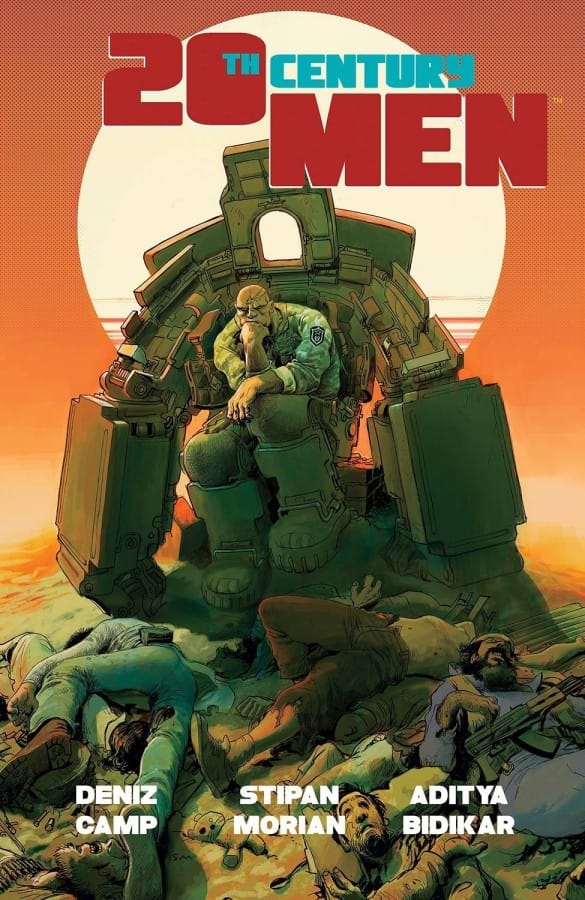

20th Century Men by Deniz Camp, Stipan Morian, and Aditya Bidikar (Image Comics)

20th Century Men is a fantastic realpolitik take on the idea of superheroes. What if America had a super-soldier? And he became President? And what if the Soviet counterpart was deeply enmeshed in the war in Afghanistan in the 1980's? This fantastic comic takes the Watchmen-esque approach that rather than be out there doing general vigilante activity, superheroes would be a pure extension of the state and the military-industrial complex. Within the world of the story where superheroes and iron men are real, the story itself feels very real and the dialogue from Deniz Camp is naturalistic and subtle. The art from Stipan Morian is just fantastic - emotive and dynamic and at points quite brutal. This is a clever, thoughtful, emotional series that will reward repeat readings. (jk)

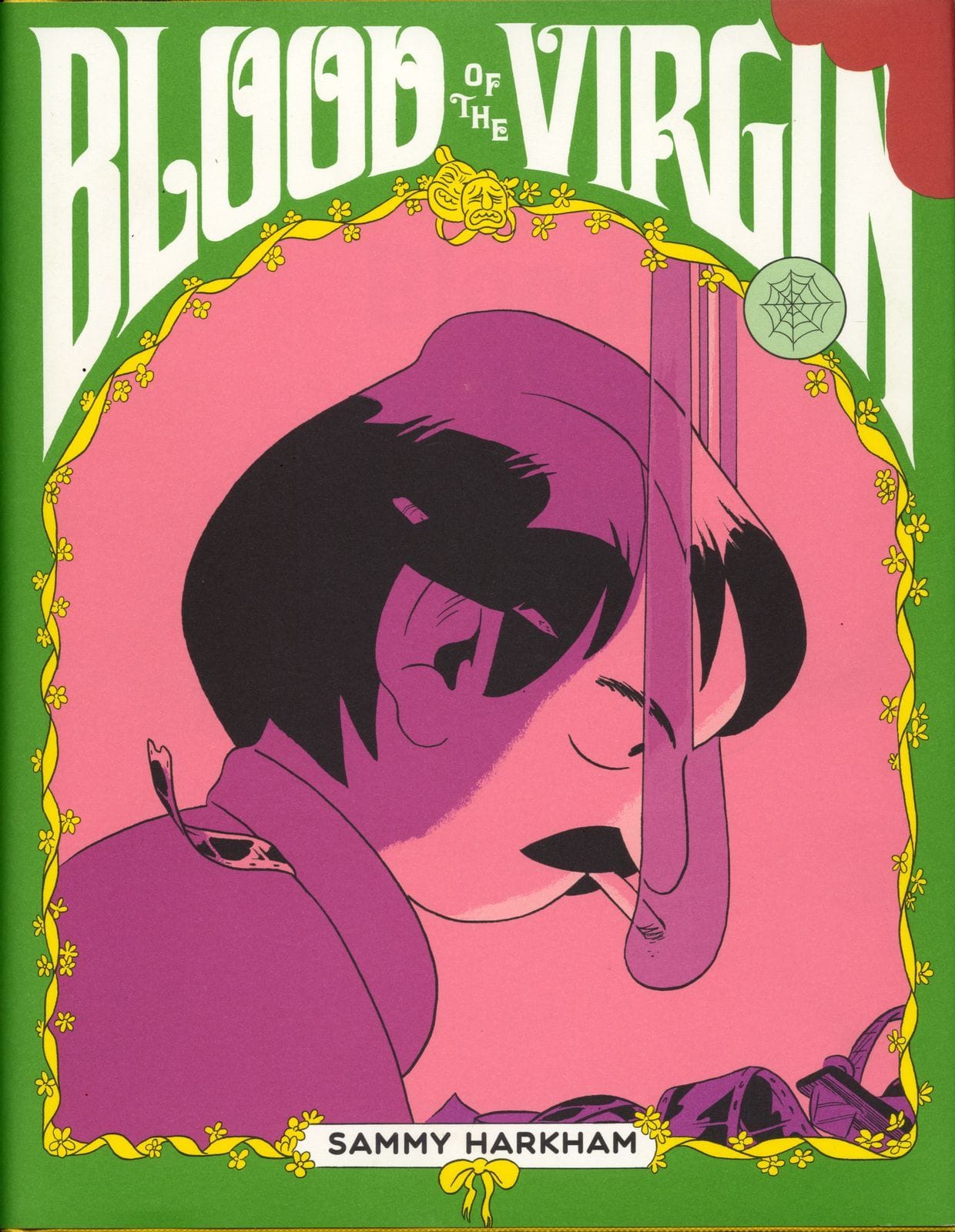

Blood of the Virgin by Sammy Harkham (Pantheon Books)

Reviewed here.

On the surface, this book about the last holdouts of the old movie studio system making their exploitative horror movies is a great look at the behind-the-scenes happening of the fictitious movie Blood of the Virgin but Harkham makes it about so much more than that as a married immigrant couple, Seymour and Ida, struggles to find their piece of the American Dream. Harkham shows just how elusive happiness can be because we don’t even know what happiness is. It’s an idea that we think we understand but is it something that we’ve really experienced? And if we haven’t experienced it, how can we recognize it? Seymour is a man longing for something to make him happy, for something to fulfill him and he just is not able to see his wife, his child, and his career in front of him. He’s blind to the things that he wants. Harkham’s story frames this longing for the things that America promises against the immigrant experience of leaving their past to find their future. (sc)

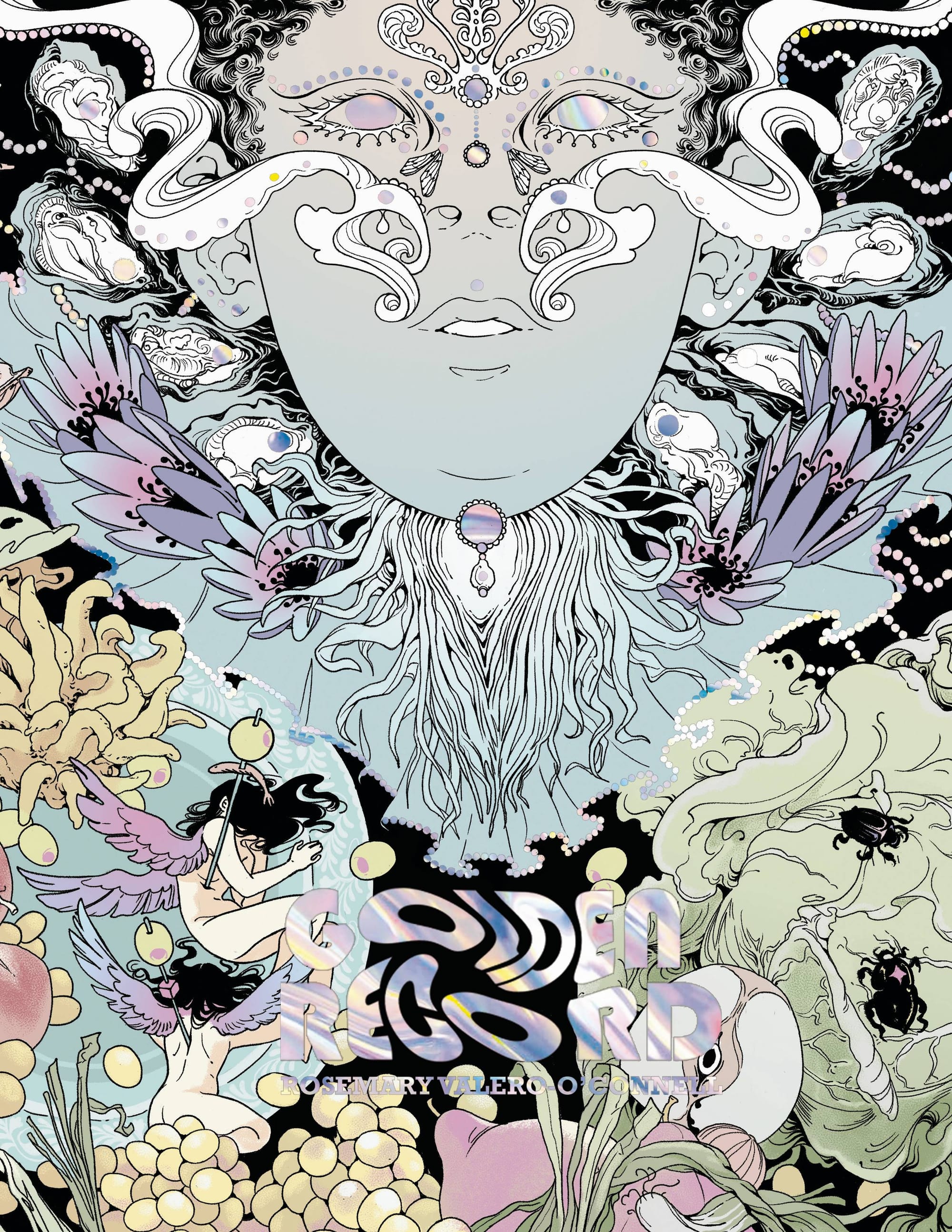

Golden Record by Rosemary Valero-O’Connell

Silver Sprocket

Golden Record is different than most books you’re going to encounter on the stands this year, or any year for that matter. Less a graphic novel or comic than an illustrated collection of poems, Golden Record is as opulent as it is surreal. Rosemary Valero-O’Connell’s poetry would be enough for me to pick up the book alone. Her playful couples, and dare I say, hendecasyllabic line structure coupled with layered, occasionally distorted, incredible, surreal, and often paisley-punctuated illustrations convey this minimalist-maximalist dynamic that is simply sublime. Is it a comic? I don’t know. But it’s my favorite thing I’ve read this year of any form or genre. (mb)

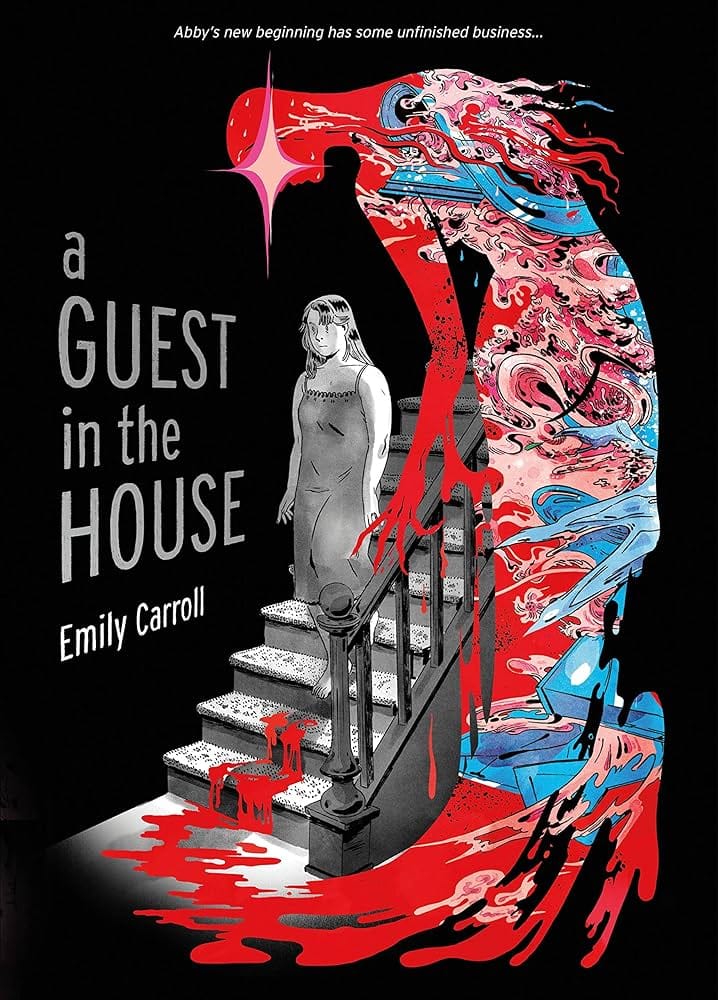

A Guest in the House by Emily Carroll (First Second)

Emily Carroll’s tale of a marriage haunted by the past was one of the most breathtaking reads of the year, as a young wife Abby has to deal with the ghosts of her husband’s first marriage, including a step-daughter who has not been able properly to mourn her mother. Abby builds up this fantasy around her husband’s first wife, a woman she never met but whose responsibilities she bears. Carroll builds her gripping and thrilling narrative around these dreams of a ghost that we can’t help but get pulled into. We experience Abby’s imaginings with a mixture of thrill and reluctance as nothing in this story feels as solid as it should. Like Abby, we have one foot in reality and one foot in fantasy, and neither world provides any solid foundation and as a reader, that’s a fantastic place to be to give yourself over to Carroll and her comic. (sc)

The Gull Yettin by Joe Kessler (NYRC)

I wrote about this book around its time of publication and I was still equally transfixed by it when I returned to it before composing my year-end favorites. Kessler’s pages are vivid and bombastic, and, despite the lack of words, I’d find myself continually “re-reading” each page to take everything in. Kessler’s ability to portray character acting and pinpoint emotions while using stick-figure drawings is utterly remarkable. And balance - there is such a sense of balance within this book. Kessler allows it to be touching and emotional without becoming overwrought or melodramatic. It’s a tender book of tragedy. (mb)

Hexagon Bridge by Richard Blake (Image Comics)

In writing about Hexagon Bridge, I'm struggling to exactly describe Richard Blake's art style. This is a sign that something feels entirely original to me - the fact that I feel like I lack the vocabulary to describe what I'm looking at. Blake's art is a revelation, as is this comic. This story takes place several thousands of years in the future, as a husband and wife who are cartographers who have traveled into another dimension to map it and have gone missing. Their daughter, along with her grandfather and a team of scientists, have spent years searching for a way to navigate into this other dimension. They're now doing so with the help of the help of a highly advanced robot built for this purpose and linked telepathically to the daughter. That's the plot of the story, but none of that serves to describe how original, weird, and beautiful this story looks. Blake's art style feels vaguely evocative of Moebius, but only in the intricate and complex nature of the worlds, not so much in the specific linework. He uses delicate lines for his work, and the worlds he is building are remarkable. The story is often a blend of what look like old classical European cities, mixed with impossibly complicated futuristic geometric shapes and towers. Blake himself notes that his work is full of experimental, abstract elements. Maps and cartography are a great way to further understand this series, as so much of the art here feels very "designed" and "mapped". It feels a lot like puzzle pieces, as sometimes the art on the page feels like a selection of the pieces of a puzzle floating in nothingness. It's otherworldly. Blake's background is in fine art and film, and remarkably Hexagon Bridge is his very first published comic artwork. That's incredible but in some ways not surprising - having spent so much time doing something other than drawing comics, Blake's style is much less bound by traditional comic art norms, and is more influenced by images and by the language of film. This is a remarkable, special comic and I highly recommend you pick it up. (jk)

In Limbo by Deb JJ Lee (First Second)

*Note: This is a memoir about Deb JJ Lee’s high school years, and in the book, Deb uses she/her pronouns. However, Deb identifies with they/them pronouns.

I eagerly anticipated this book at the beginning of the year but only read it a week ago. It was worth the wait. Deb JJ Lee’s control of their narrative structure via their cartooning prowess leads to a book I can describe no better than complete. Memoirs are a tricky genre, and those about high school years are among the hardest to pull off without injecting too much of one’s current self into the story or leaning too far into the melodrama that is teenage life. Lee achieves this balancing act with nimble precision. It is clear this is a serious book; it is a tight narrative, focused and clear. Lee is both thoughtful and economical in their storytelling. The Deborah Jung-Jin Lee we encounter is an honest character, and In Limbo chronicles four years of high school as Lee pulls back their/her layers. She is honest and vulnerable. At times, you’re enraged for her, other times you are rooting for her, and still other times you are frustrated by her. I found Lee’s ability to convey all of these feelings about their teenage self to be both impressive and touching. More importantly, they don’t fall into the trap of fixing everything for Deborah. Things get better, yes, but they’re not perfect. This story doesn’t have a happy ending as much as a satisfying one. Lee captures loneliness in a way that is precise and unique to this story, with tones of tragedy and failure punctuated by just enough of their own retrospective analysis and tacit understanding that the four years of high school are simply that. But it isn’t pollyanna. It’s not an “it gets better” redux. No, it’s very much a picture of a young person navigating adolescence and realizing the nature of both the world and their part in it. Deborah encounters racism both directly and indirectly. She struggles with identity, friendship, and self-image. Lee’s depiction of their relationship with their mother is brutally honest and at times honestly brutal. Deborah experiences pressure from both within and without amidst cultural stereotypes and typical ignorance. But nowhere in the book does Lee let Deborah descend to victim status. Artistically, this book is magnificent. Lee’s soft lines and textured shading pair with intricate backgrounds that absolutely mesmerized me. Lee illustrates digitally, and I honestly cannot tell if they hand-illustrated on top of real images of New York City streets, or if they captured these backgrounds with a level of absolutely unparalleled verisimilitude. I strained my eyes squinting at these pages. I obviously don’t know enough about the creation of art to figure it out, but I was blown away either way. (mb)

The Incredible Hulk by Phillip Kennedy Johnson, Nic Klein, Travel Foreman, and Matt Wilson (Marvel Comics)

I love the Hulk as a character but I am hit or miss on actual Hulk comics. The Immortal Hulk was a series I really loved, and I felt a loss when it ended (it's really one of the best superhero comics of the past decade). The Hulk series that followed was not really for me. However, I'm thrilled to say that the current run of The Incredible Hulk is very much for me. What I like about the Hulk comics is that there are so many ways the story can go. They can be scary stories, they can be action stories, they can be big, epic, and can also be intensely personal. This current story is very rooted in Hulk's origins as a horror comic creature, exploring Hulk's ties to some of the other "monsters" of the Marvel Universe. Hulk is a loner, and he and Banner are very much at odds and they've picked up a sidekick in a troubled teen who sees the strength of the Hulk and wants to be strong like him. The art duties have been split between Nic Klein and Travel Foreman. They have very different styles from one another but both of them are incredibly skilled storytellers, and both of them excel at drawing some of the most HORRIFYING things you'll see in a mainstream superhero comic. Like when Banner turns into Hulk - yikes, it's pretty terrifying. But that's awesome. I love seeing Hulk explored as a monster among monsters; it's an incredible read. (jk)

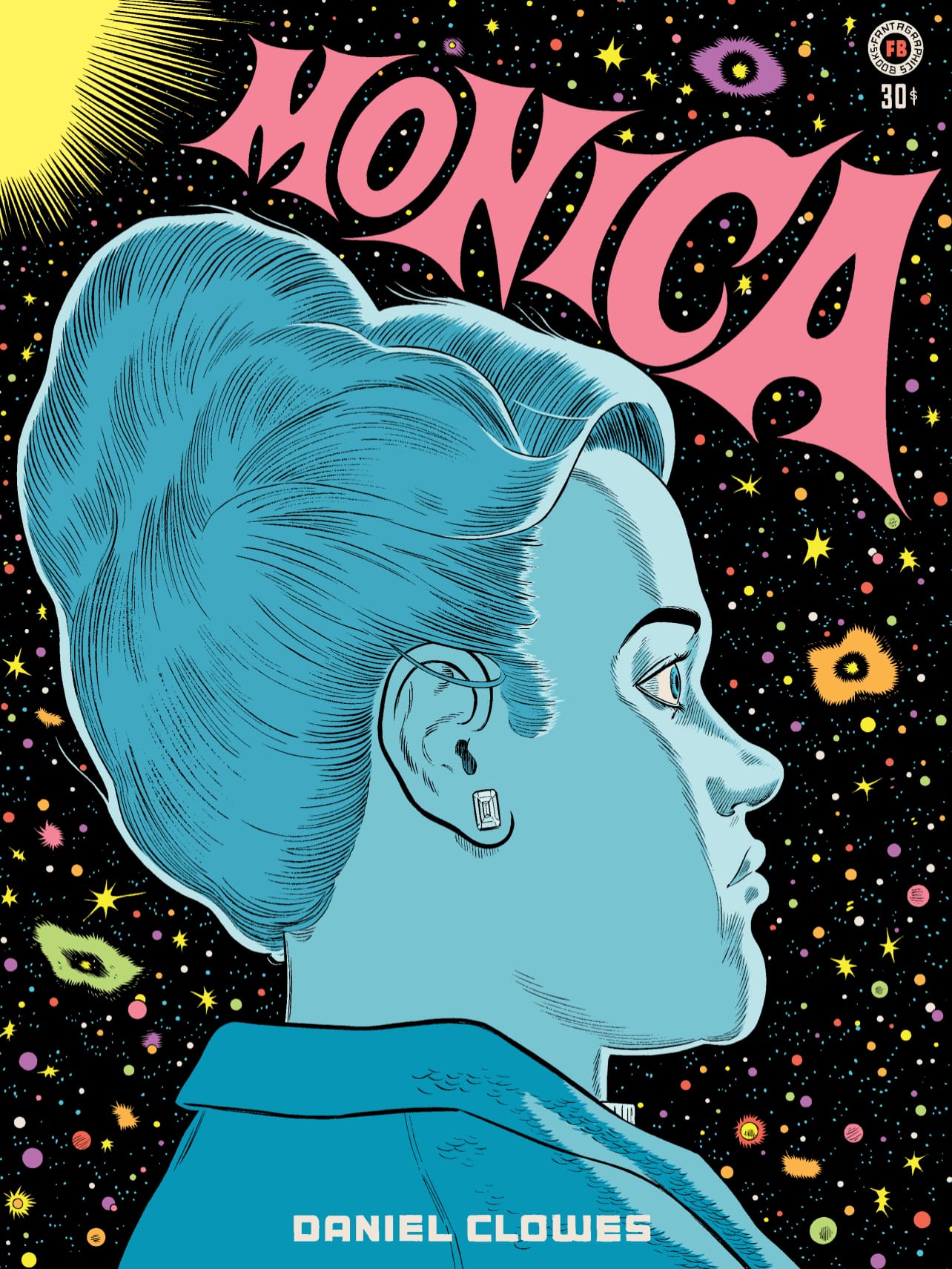

Monica by Daniel Clowes (Fantagraphics)

There’s something about trying to find our own story even as we’re living it that Clowes recognizes as a universal experience in this excellent book. Abandoned by her mother when she was a young girl, Monica spends her life trying to figure out who she is in relationship to that missing mother even as she’s living her own life and defining who she is without her mother. Clowes tells this story through EC-like stories, creating a book that’s both a one-man anthology as well as a rich novel. (sc)

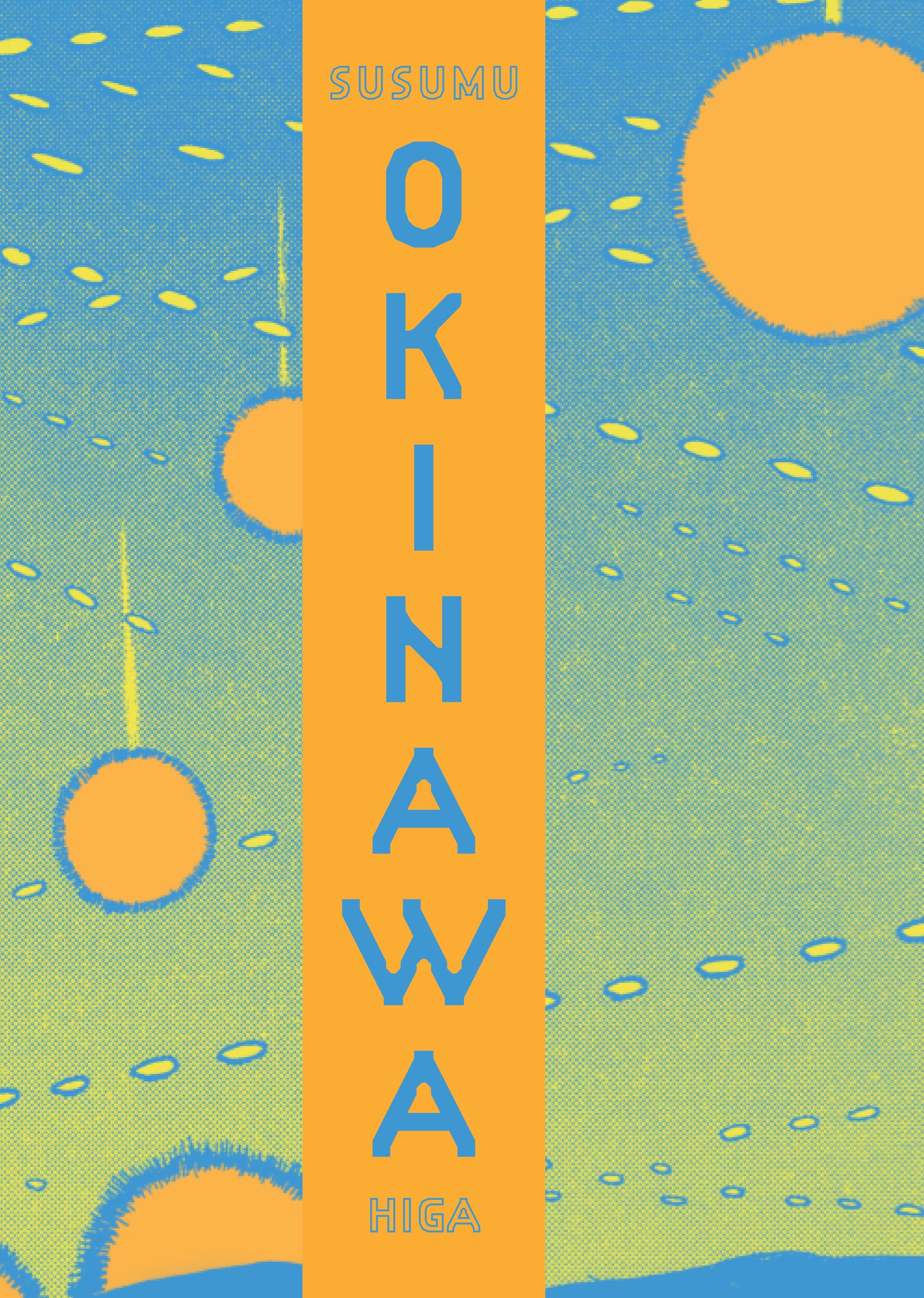

Okinawa by Susumu Higa (Fantagraphics)

Continuing a theme of honest and thorough accounts, Okinawa is a masterpiece in every sense of the word. Published in Japan in installments, there is a tangible benefit to reading the entire tome as one publication. Higa constructs a multigenerational epic replete with tragedy and perseverance. It’s a hard book in that one cannot sit and read it with that familiar feeling developing in the pit of one’s stomach, that awful feeling of oppression and injustice. The Okinawan/Ryukyuan people are caught in between the conflict between the American and Japanese armies during World War I. They suffer differently at the hands of both armies, but perhaps the last third of the book, if not more, is devoted to the ongoing American military occupation of the island of Okinawa. The beauty of this book is the way Higa imbues a sense of grace amidst the profound tragedy. Despite the heartache, Higa aims his focus at resilience and, dare I say, empathy. As touching as it is informative, I can’t think of a book that was harder to put down this year. (mb)

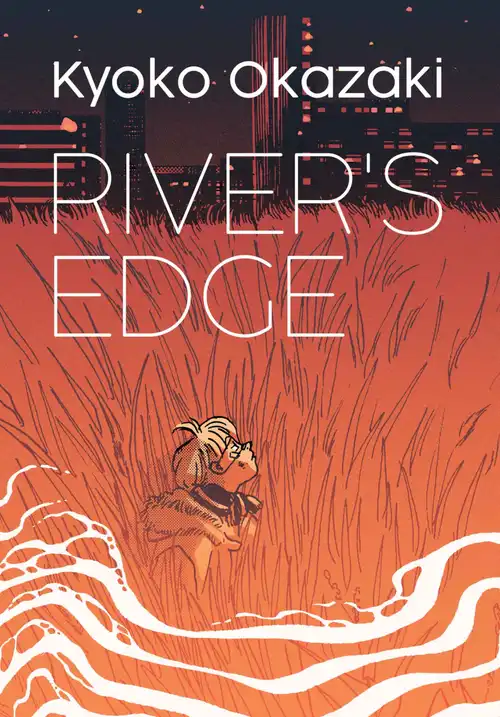

River’s Edge by Kyoko Okazaki (Kodansha)

Reviewed here.

This brutal story of teenage alienation still haunts me months after reading it. Okazaki's artwork is like raw, exposed nerves and her story is the shocks that stun the body when those nerves are touched and prodded. Okazaki isn’t gentle about how she treats her characters or her readers, showing friendship and companionship as something desired but less than real in this high school story of kids just trying to survive the year. (sc)

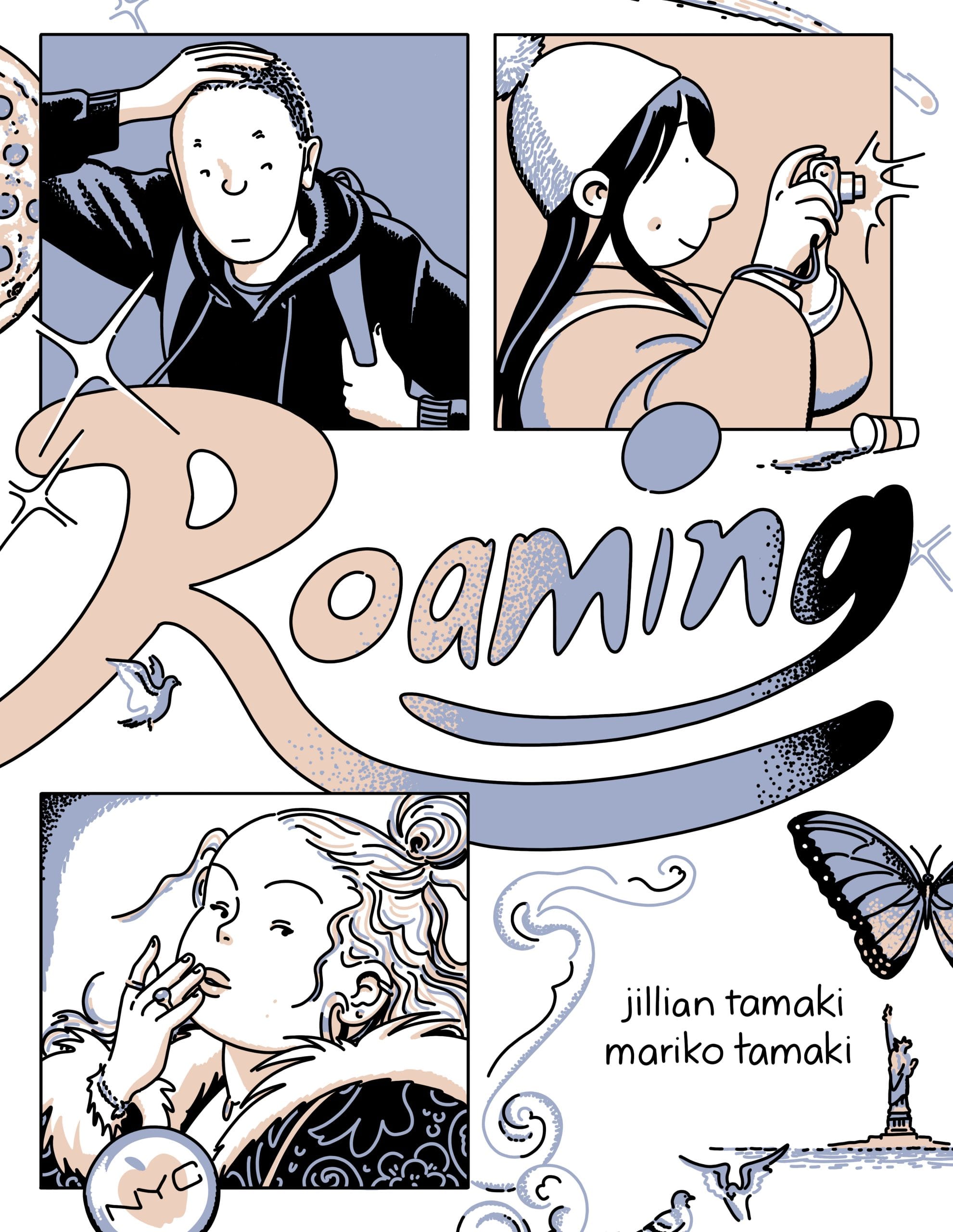

Roaming by Mariko Tamaki and Jillian Tamaki (Drawn & Quarterly)

Roaming was such a delight of a graphic novel, as it told such a specific, personal, yet entirely relatable story. Roaming tells the story of 2 Canadian friends (Zoe and Dani) who are now freshmen at different colleges, that meet up in NYC in 2009 to spend Spring Break together. Dani brings along her friend Fiona from college. So...that leads to all sorts of consequences, as this was going to just be a "2 best friends together" trip and it turns into something very different. There are all sorts of awkward dynamics and so many of them are incredibly true to life. I absolutely *knew* several "Fionas" in college; they were both such a trip to be around and reading this story brought all of those memories to life for me. Mariko and Jillian work brilliantly together. Jillian's art is wonderful; the characters are done in an exaggerated style, but everything about their environment is brought to life in a very real way. Her attention to detail is unmatched, and I really *feel* the streets of NYC circa 2009. I absolutely adore this book and would recommend it for anyone looking for a great story of relationships, and trips gone awry, and what it's like to be young and uncertain and make dumb mistakes and to think you're much smarter than you are. (jk)

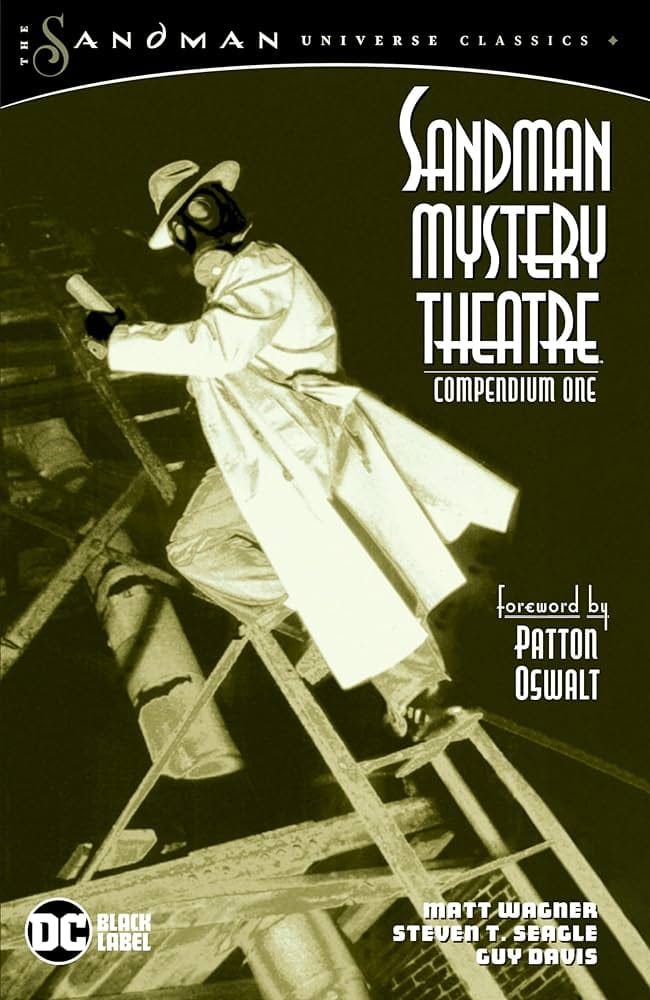

Sandman Mystery Theatre Compendium V1 by Matt Wagner, Steven T. Seagle, and Guy Davis (DC Comics/Black Label)

Since the 1990s when this series first came out, there have been on-again/off-again efforts to collect it but each time it’s been abandoned somewhere short of completion. DC’s new compendium collection (about 30+ issues or half of the series) reveals a timeless collection of pulp stories that contain so much more than any possible genre limitations. Matt Wagner kicks off this collection with some of his best and richest writing where we see a real relationship between Wesley Dodd and Dian Belmont grow, flourish, and stumble as they fall in love. Steven T. Seagle steps in as co-writer after a dozen or so issues and this writing duo along with Guy Davis’s gorgeous and intriguing art write one of the most adult stories that ever came out of the Vertigo line. There’s a romance that’s nurtured against all of these tales of depravity and brutality. (sc)

Spy Superb by Matt and Sharlene Kindt (Dark Horse)

I am here for any new content from Matt and Sharlene Kindt, particularly if it is drawn by Matt and colored by Sharlene. I love Matt Kindt as a comics writer, but I particularly am a huge fan of when he and Sharlene go full cartoonist. One of Kindt's earlier series, Super Spy, is a favorite of mine, as it has many different interconnected spy stories set in the same universe (and was rereleased by Dark Horse in a beautiful hardcover). Super Spy tells a complex, interconnected story. 52 of them, in fact. Each one is numbered as a “Dossier” and they’re included in the book out of sequence. If you want, you can choose to read the Dossiers in numerical order in order to read the story in chronological sequence. I’ve never done this, as I prefer to read the story as a series of puzzle pieces that come together over time as I read the story. Spy Superb is the new series from the Kindts and it seems to be set in the same universe as Super Spy. It concerns the delightful premise of a "non-traditional" spy who is the greatest spy ever. The way this spy functions as the greatest spy ever is that they do not know they're a spy; or, rather, they think they're a spy but have no idea what their actual missions are or what they're doing. The main spy in this story is a memorable idiot that you'll hate, love, and pity all at once. The story has twists and turns and the art from the Kindts has never been better. (jk)

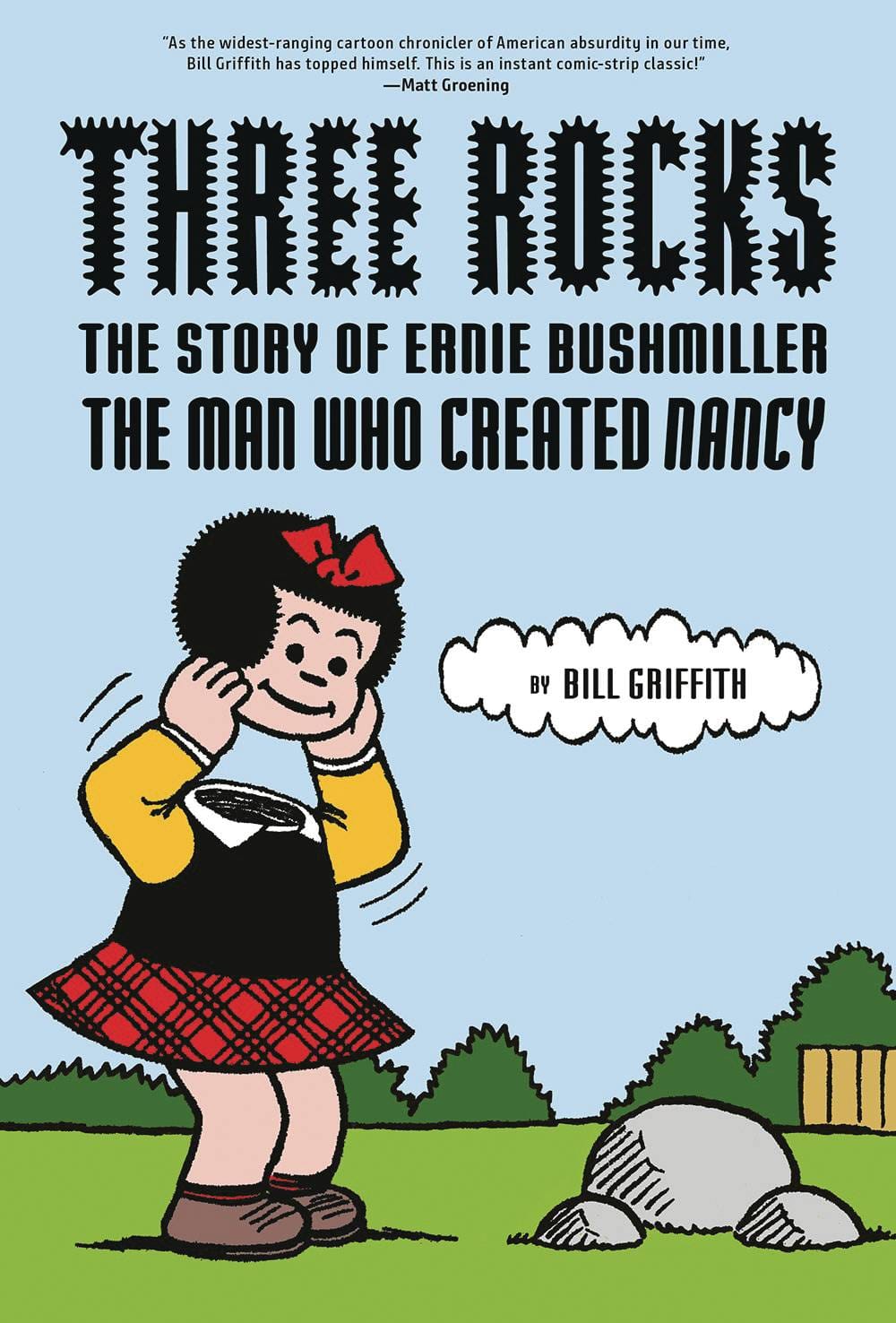

Three Rocks: The Story of Ernie Bushmiller, the Man Who Created Nancy by Bill Griffith (Abrams Comicarts)

Popular discourse around the majesty of Nancy, and thereby her legendary creator, Ernie Bushmiller, reaches a zenith with fellow master cartoonist Bill Griffith’s comprehensive and thoughtful biography. Griffith‘s analysis of Bushmiller is both scholarly and personal. At times, Griffith, he of Zippy the Pinhead fame, feels like he is directly communicating with the soul of Ernie Bushmiller. More than just a biography of Bushmiller, or of Nancy as a character, it is an exegesis of the entire history of the strip from an insider’s perspective. Griffith’s credibility as a renowned cartoonist creates a specific authority for how he breaks down Bushmiller’s genius. As a result, components lean into a literacy biography. But there is also love and fondness. I’d contend Griffith mostly tempers his sentimentality, but it certainly creeps in from time to time. However, part of that fondness is why the book resonates with a particular charm. There is a dichotomy to Bushmiller and, by default, Nancy as both a strip and a character, governed by the fundamental questions surrounding what is art. Is Nancy a serious strip that doesn’t take itself seriously? Is it high art for the low brow, or the reverse? Griffith’s characterization of Bushmiller is that of an Everyman, and he might be the truest definition of that term in that Nancy touches both the scholar and Bushmiller’s “gum-chewers” with a similar power. Griffith’s coup in this book is presenting Bushmiller’s strip philosophy for the average reader, one he punctuates beautifully by rearranging Bushmiller’s own strips to tell a large chunk of the story. The feat amazed me as I was certain Griffiths was endlessly redrawing Nancy and Sluggo to tell their story until I read the author’s note at the end of the book and immediately started paging backwards in disbelief. (mb)

Comments ()