The Kids Aren’t Alright in Kyoko Okazaki's River’s

How can you have compassion for other people when you have none for yourself?

In the field next to a high school, there’s a decomposed dead body that’s been there for a while but only known by two or three students. That should almost tell you all you need to know about the environment that Haruna Wakakusa, Ichiro Yamada, and their classmates are coming of age in. Kyoto Okazaki’s River’s Edge is an odd coming-of-age story, focused on the tragedy and heartbreak of realizing how cruel the world is. Now these are high schoolers and cruelty is a natural part of high school. So when Yamada gets stuffed in a school locker by Haruna’s bully boyfriend Kannonzaki, it feels like something out of a John Hughes film like Sixteen Candles or The Breakfast Club or one of those sanitized views that hold that the kids are alright and it's everyone else that’s screwed up. Okazaki tells the story about an environment- that’s why the field and dead body are so important- that’s built up to prepare these kids to accept a world that will fight them at every turn. And it seems to be doing its job extremely well.

This is a high-school story but it isn’t the kind that we’re largely programmed to accept: there’s no brain, no beauty, no jock, no recluse, and no rebel. Those labels are too easy for Okazaki to accept or to fall into. None of these kids are any one thing. Haruna is this girl who crosses the social boundaries set up in high school; she’s got a good group of friends (who all have their crosses to bear) but for some reason is dating the school bully and drug dealer. Yamada is this shy, sensitive, and gay boy who’s struggling to find acceptance which is something that Haruna gives to him when she rescues him from Kannonzaki’s cruelty. Haruna’s best friend Lumi looks for outside validation of her wealth, often finding it in older men who shower her with gifts. Okazaki shapes her cast to embody the insecurities and fears that too often we let have power over who we are. Even Kannonzaki, for how repulsive of a kid he is, exhibits moments of vulnerability that only Haruna can recognize.

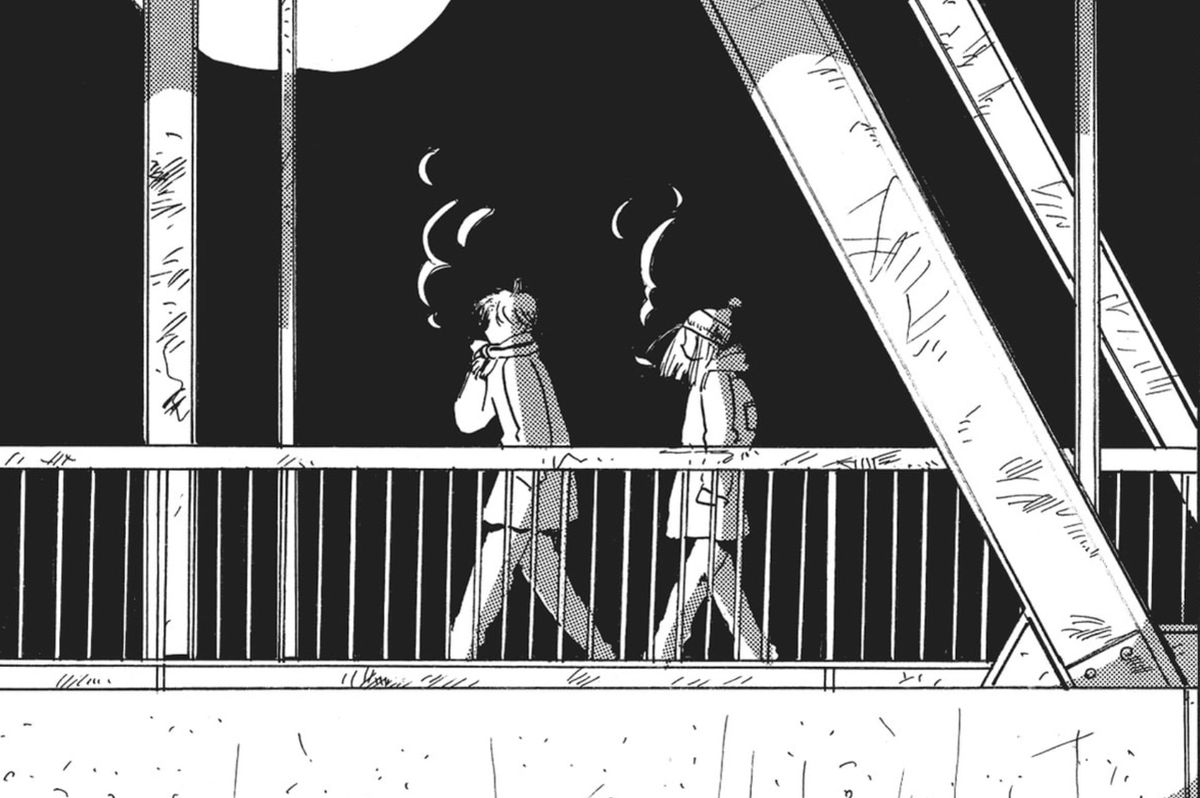

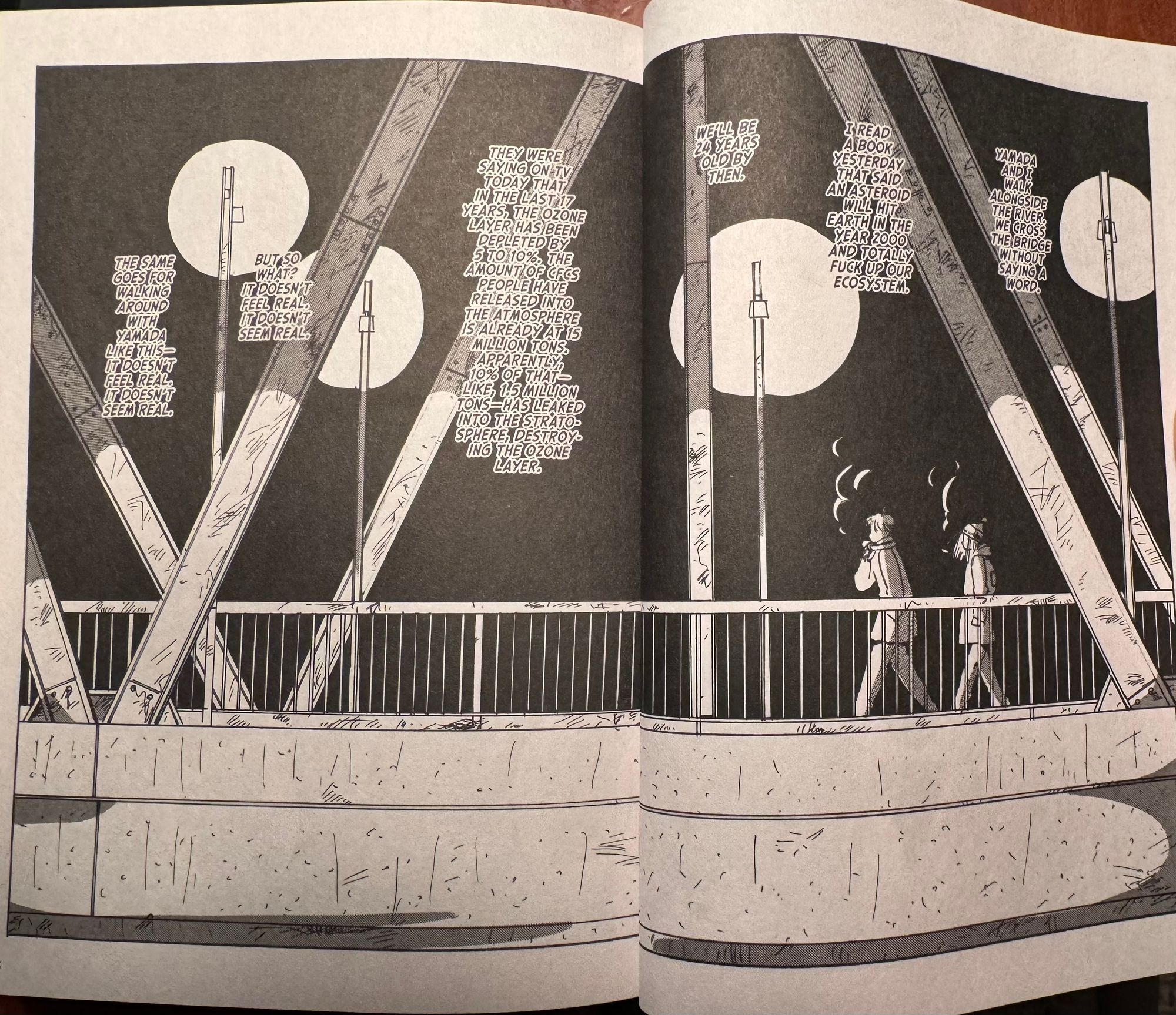

So while there’s recognition of what other people are going through, no real connections are being made- no one really knows anyone else. They think they do; they have their ideas of who their friends, boyfriends, and classmates are but at best, it’s only a surface-level knowledge of who the other people are. When Yamada repays Haruna’s kindness and shows her his “secret treasure” in the field, the dead body initially shocks her but that also is only a surface-level reaction to it. “But it didn’t feel real,” she tells us once she’s processed it a bit. For Yamada, it’s something meaningful; “I never know whether I’m dead or alive,” he tells her. “When I look at it, it gives me courage.” It’s an odd confession coming from a kid she barely knows while she feels nothing because she can’t acknowledge the reality of the moment. Or maybe it’s the need Yamada has to hold onto something that she can’t relate to. She knows that she should feel something here- fear, disgust, fascination, or something else- but for her, it’s almost like this is something else completely outside and separate from her.

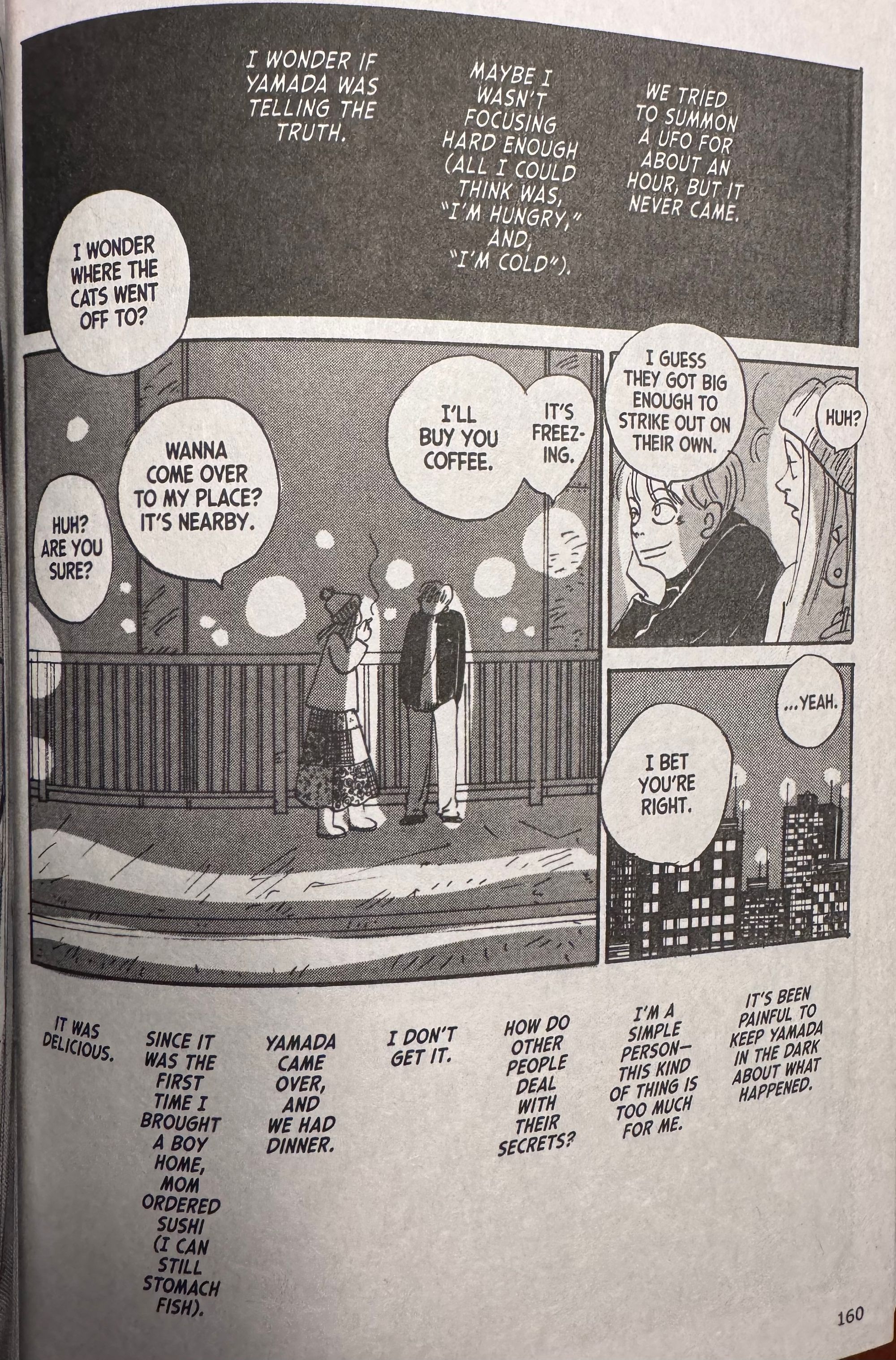

This disconnectedness is how Haruna largely experiences the world. Explaining the first time she had sex with Kannonzaki, she describes her reasons as “… not because I loved him or anything. I think it was more that I wanted to just see what sex was like.” She then goes on to say that it’s “easy to have special emotions for your partner” but doesn’t dive into what those emotions could be. And it’s not like Kannonzaki is a great boyfriend or anything; while Haruna is in the field with Yamada and the dead body, Kannonzaki is in a love motel with Haruna’s friend getting high and screwing her. These kids live in this tight community but can’t see the world beyond themselves.

Okazaki lets these kids live their messed-up lives. It’s a bit of tough love she has for them as you can see her letting them make mistakes but hoping that they’ll learn from them. They’re all on the same journey are Haruna, just at different endpoints of it. Haruna is the one who begins to see beyond herself to develop some true connections with others. The first time she slept with her boyfriend, it was just for an experience, to see what it was like. The second time she sleeps with him happens after she apologizes to him for not being there when his family was having some trouble. “As for why, I don’t think it was motivated by like or dislike, or love or longing. It was more like I wanted to say thank you and I’m sorry, or something like that.” These characters take small steps toward growth and occasionally step back again.

River’s Edge is a mass of raw, exposed nerves from the first pages through the end. Watching these kids is both recognizable and painful. Haruna is the source of this story as everything flows through her. She’s the gravity that brings all of these kids and their stories together so we see everyone’s story through her. Okazaki is honest and raw in her storytelling, letting us live through these characters and see how we could make the same choices and mistakes that they do. In the end, this story is about empathy and how it develops in us (or maybe even how it doesn’t.).

Comments ()