The Gull Yettin is a Minimalist Masterpiece

Form is at the heart of Kessler’s art. As free-flowing, and perhaps occasionally haphazard as it might seem on first blush, it is ultimately an exercise in precision.

Fair warning: This review is going to be effusive, to say the least.

Almost invariably, when I read a wordless graphic novel, I tend to blow through it fairly quickly. The narrative is usually sparse enough that my main endeavor is taking in the art on its own terms. I would contend that for most wordless graphic novels, the narrative is secondary to the art. But Kessler’s work is far different. I’ve never read anything like this before, wordless yet somehow absolutely complete in terms of its narrative ambitions.

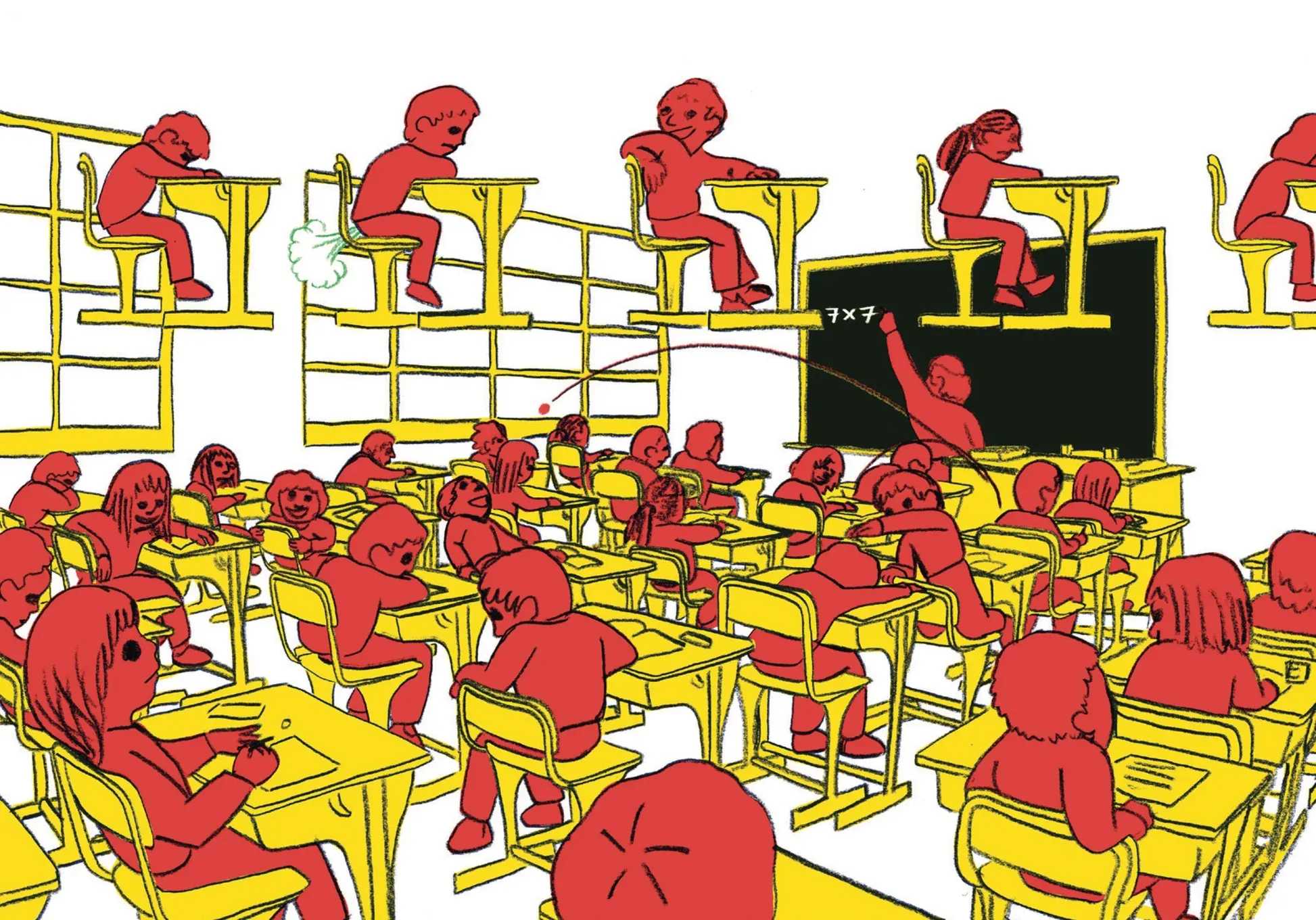

I found myself examining every page, looking for even the most minute detail, both to take in the mesmerizing free-form beauty of every panel while also working to graph each position of the incredibly precise, fully formed story Kessler executes. It is not hyperbole for me to say that, in The Gull Yettin, Kessler does more without words than I could have possibly imagined. Most wordless graphic novels require much more work on the reader’s part to assemble the structure of the story, and it’s frankly astonishing how well laid out The Gull Yettin is. Kessler’s coup is his ability to impart significant emotion and narrative substance merely through body language and positioning. That he achieves so much with a fundamentally minimalist, fairly abstract style is mind-boggling. However, Kessler’s expressionism channels through his command of form, not the dissolution of it.

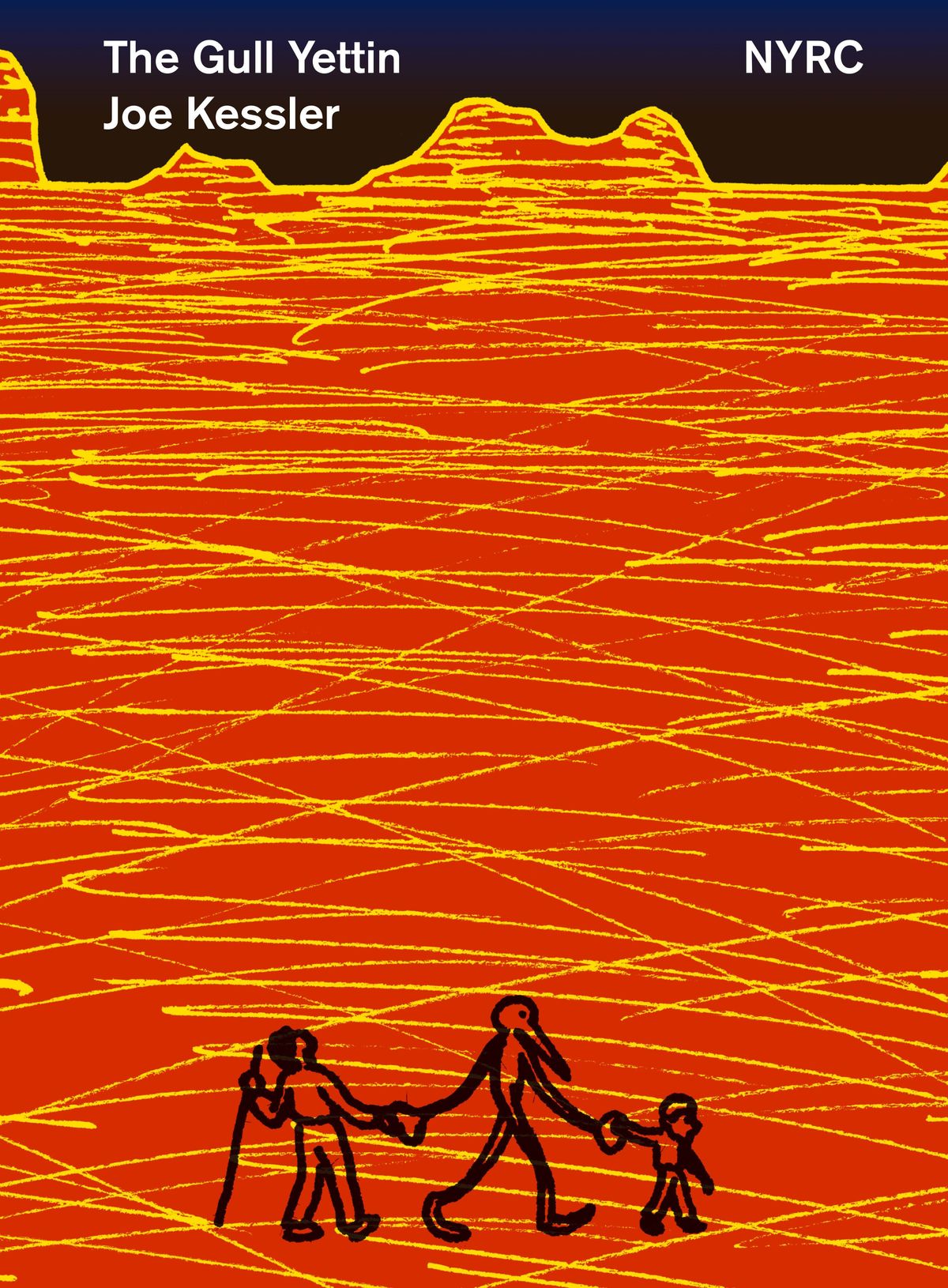

The Gull Yettin is a modern fairy tale of sorts set in a non-specific part of the late 20th century, possibly in the bleed between modern and postmodern. It feels funny to consider the temporal distance from this timeframe, one where screens exist, but are rare and hardly dominant. This is possibly a time I’ve lived through, or perhaps the remnants thereof. At the very least, there is both a charm to the familiarity and panic at realizing how much things have accelerated since. That thirty or so years ago could evoke such nostalgic comfort in a way decidedly more ancient fairy and folktales do is a staggering feeling.

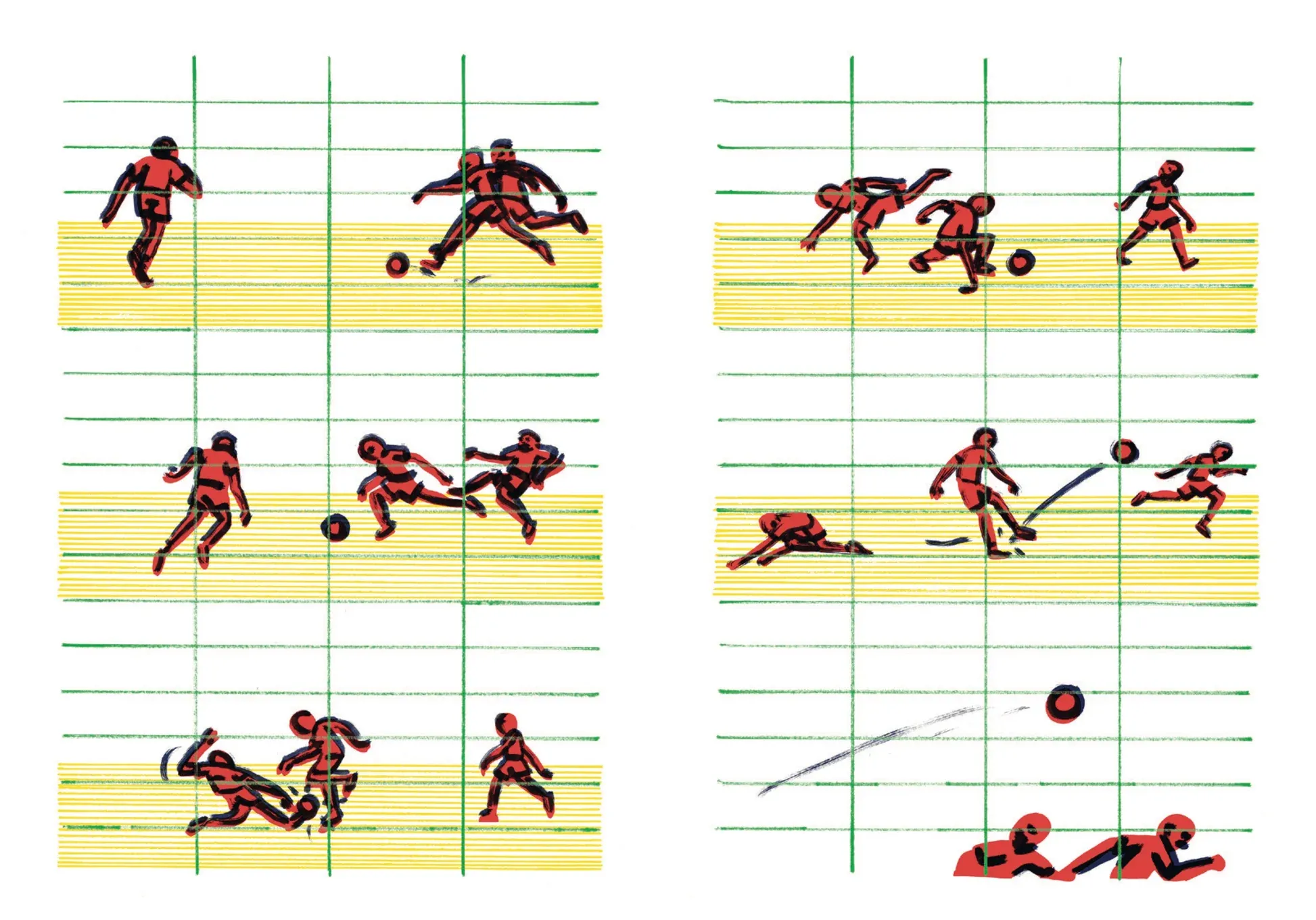

Our story starts with a pair of brothers at afternoon football (soccer) practice. From the first few pages, you get the sense that Kessler is damn serious about what he is putting on the page. I was mesmerized by the flow of the football as it careens towards the goal, the angle of the children’s limbs as they run the pitch - this is serious work not belied in the slightest by its minimalism. Kessler expertly conjures the frenetic feeling of football practice. It feels almost divorced from everything else going on around it as if it’s the only thing that exists in the world, and that is the exact feeling we’d all get when we’re engaged in sport. These boys seem to be of a specific precious age. They seem old enough to have some degree of independence, but are very much still little kids, perhaps somewhere around seven or eight.

Following practice, one of the two boys notices a bird perched on a ledge as they walk home. He flicks a button to the bird as a little token of friendship and proceeds on his merry way. Unbeknownst to him, another anthropomorphic bird creature (perhaps the same bird transformed, perhaps some ethereal being) takes interest and follows him home. Later that evening, our protagonist’s house catches on fire. It’s a deadly, overwhelming blaze, and our boy appears orphaned and injured.

As tragic as an event this is, it is some of the most beautiful art in the book. It had some degree of familiarity, possibly recalling the kinds of sketches children make on lined loose-leaf paper, chaotic marker lines strewn across it. And it is, to some degree, just that, but it is so much more refined in ways I’m going to have difficulty explaining. But I’ll do my darndest.

When I was in college, I had a philosophy professor who told me that the deconstructionists were the most formalist of all. When everything is broken down, there is nothing left but form. I never entirely bought into that contention, and I’m positive Derrida would not have agreed either, but I realized Father Thayer (that’s right, this man was a Catholic priest who specialized in contemporary philosophy, was fairly radical in his outlook, and who smoked Marlboro Reds before class) might have been on to something as I was reading The Gull Yettin.

The form is at the heart of Kessler’s art. As free-flowing, and perhaps occasionally haphazard as it might seem on first blush, it is ultimately an exercise in precision. It isn’t as intentionally abstract as it might appear, though it certainly calls upon a certain technique of abstract expressionism. But what differentiates it from purely abstract art is that there isn’t an inherent puzzle at play. It isn’t reduced shapes or intentionally raw - no, there seems to be refinement at the core of it. At first glance, indeed, one could quite easily read into the experimental chaos of certain pages. The reader might observe the high contrast of thick, primary colors and rightfully assume intent behind the lines. But really, Kessler’s work is more minimalist than it is abstract. Yes, there are certain nods to abstract expressionism, and there are times when the form descends enough that the page seems more abstract than minimalist, but fundamentally, Kessler is focused on reducing the page down to the line, a meditation on the most rudimentary component of the form. To that degree, I could stare at these pages for hours. I don’t necessarily need a narrative: the flow of the lines is enough of a story for me. The fact that Kessler holds an exceptionally tight narrative on equal, if not elevated standing, with his artistic experimentation is why I find this book so mesmerizing. But it’s almost certainly wrong for me to break apart these two components. I do so only to point out the structures at play.

The way my mind works is very categorical. I often attempt to find antecedents, if not direct influences, for music, comics, prose, and the such. My brain simply tracks chronologically, so, despite any best efforts, and frankly without even noticing it, I tend to sequence things. It must be how my brain makes sense of things - this movement preceded this style, and so on. At first blush, I could see how one might pull a DeForge vibe from Kessler’s pages, but I think such a comparison is only fitting in a few instances. There is a definite connection of genre - or perhaps sub-genre. Each cartoonist is approaching something similar, though from different angles (and, to be fair, I would say that only certain components of DeForge would enter such a comparison with equally specific components of Kessler). To use a punk rock analogy, DeForge is the band that didn’t know how to play when they first picked up instruments but who end up creating their own beautiful music. Kessler is the band of trained musicians who deliberately play only a few chords. He is the power trio that creates far more sound than seems would be possible. So, despite my efforts, and despite the way my brain works, it’s rather difficult to discern Kessler’s genealogy. There are elements of graffiti, and you can see the Keith Haring influence at play. Some of Kessler’s coloring - specifically the beautiful and jarring house fire scene and the watercolor rowboat interlude - reminds me just enough of Tillie Walden. But fundamentally, this book is its own. I make whatever comparisons I do only to distinguish it. It’s important to realize the precision of this work, and the clear thought behind each line. As chaotic as some of these pages might appear, Kessler isn’t slapdash. It’s not lines thrown on paper as an experiment, or to channel emotion. Not this is as precise an exercise as one might find, but it could be easy to miss at first glance because that precision often arrives as thick felt tip marker figures and blocky primary color background. And I can’t help but think of Sylvia Nickerson’s Creation when I consider Kessler’s outline figures. While Nickerson’s purposeful reduction gives us artfully rendered and precise thumbnail sketches, Kessler’s figures explode from the page in some 3D sleight of hand. To go back to the music analogy, Kessler is few chords but many pedals. There is a saying about shoegaze - chords as lyrics. In the Gull Yettin, lines are dialogue. This is the type of art an idiot thinks he could reproduce, but that a renowned artist would stare at for hours.

And, at the risk of repeating myself, what makes The Gull Yettin remarkable is that all of this experimentation and reduction of form and chaotic energy exist for the sole purpose to drive the narrative of the book, to emote through those lines a sense of trauma and jealousy that deftly balances guilt and catharsis. It’s difficult to achieve such a feeling even when using words to add weight to visible events. But, perhaps that’s the real genius behind The Gull Yettin. Perhaps words get in the way. Yes, that’s precisely it. Just as Kessler eschews the conventions of form, he entirely excises the existence of prose, whittling The Gull Yettin down to its purest form, an unabashed graphic novel.

Comments ()