Welcome to the Party in Julie Doucet's Time Zone J

Julie Doucet's time away from comics has given her the freedom to just jump back into their creation, rewriting the rules about how she’s going to tell her story.

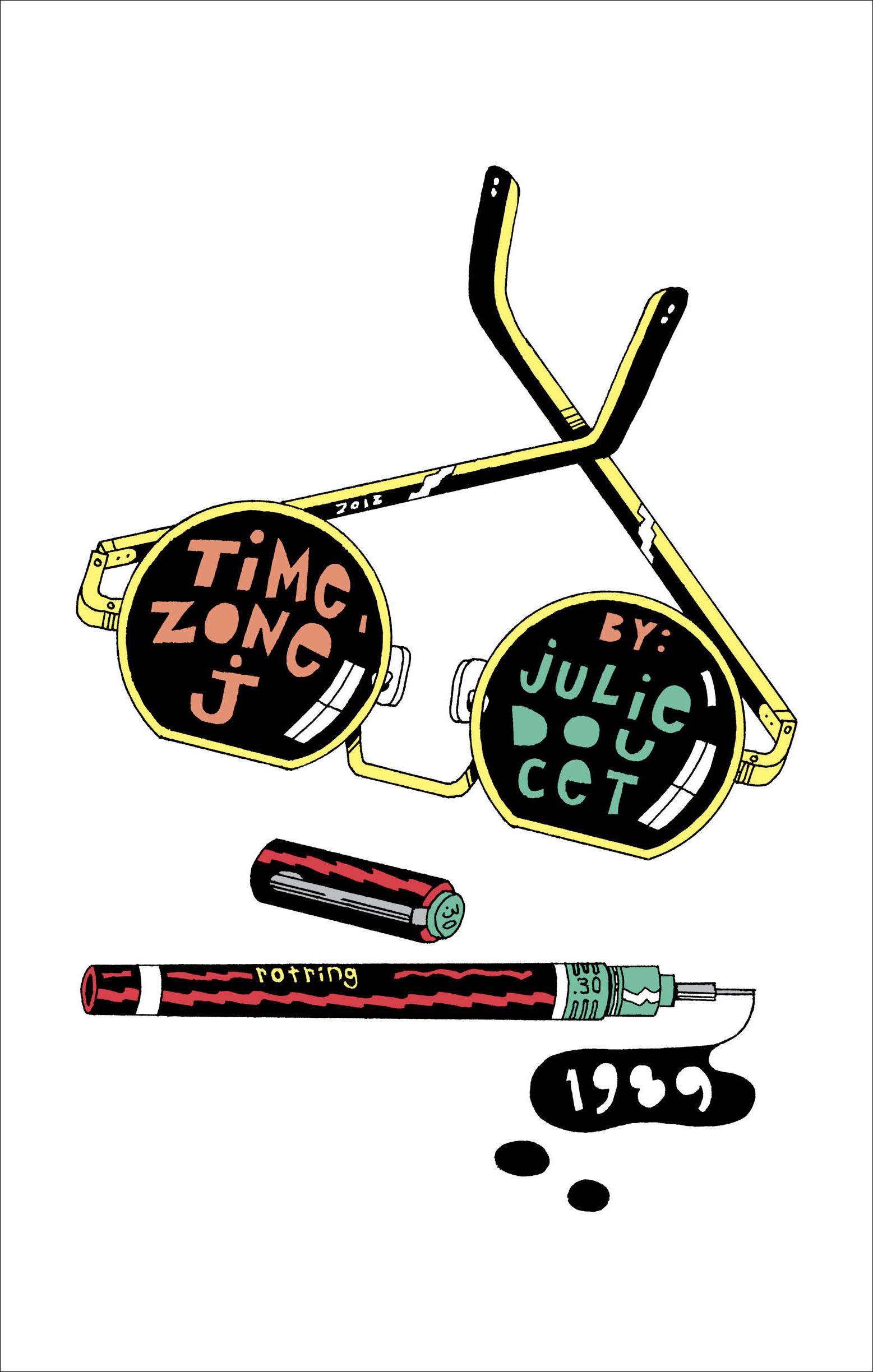

There’s a version of Julie Doucet’s Time Zone J that I hope we see one day. That version is freed from the book format and just a scrolling visual narrative with almost none of the traditional languages or structures of what we think comics should be. Clocking in at 144 pages (according to the D&Q website,) this book is one long image, each page an almost arbitrary unit of narrative where each image and mark on the page bleeds into the next page and its images. There are no panels, no borders, and no gutters to give the reader a feeling of involvement or control of the story. There are just Doucet’s images, mostly her face over and over again, and other faces looking out towards the reader; a sea of faces as Doucet tells us a story about a brief but impactful relationship that happened over 30 years ago.

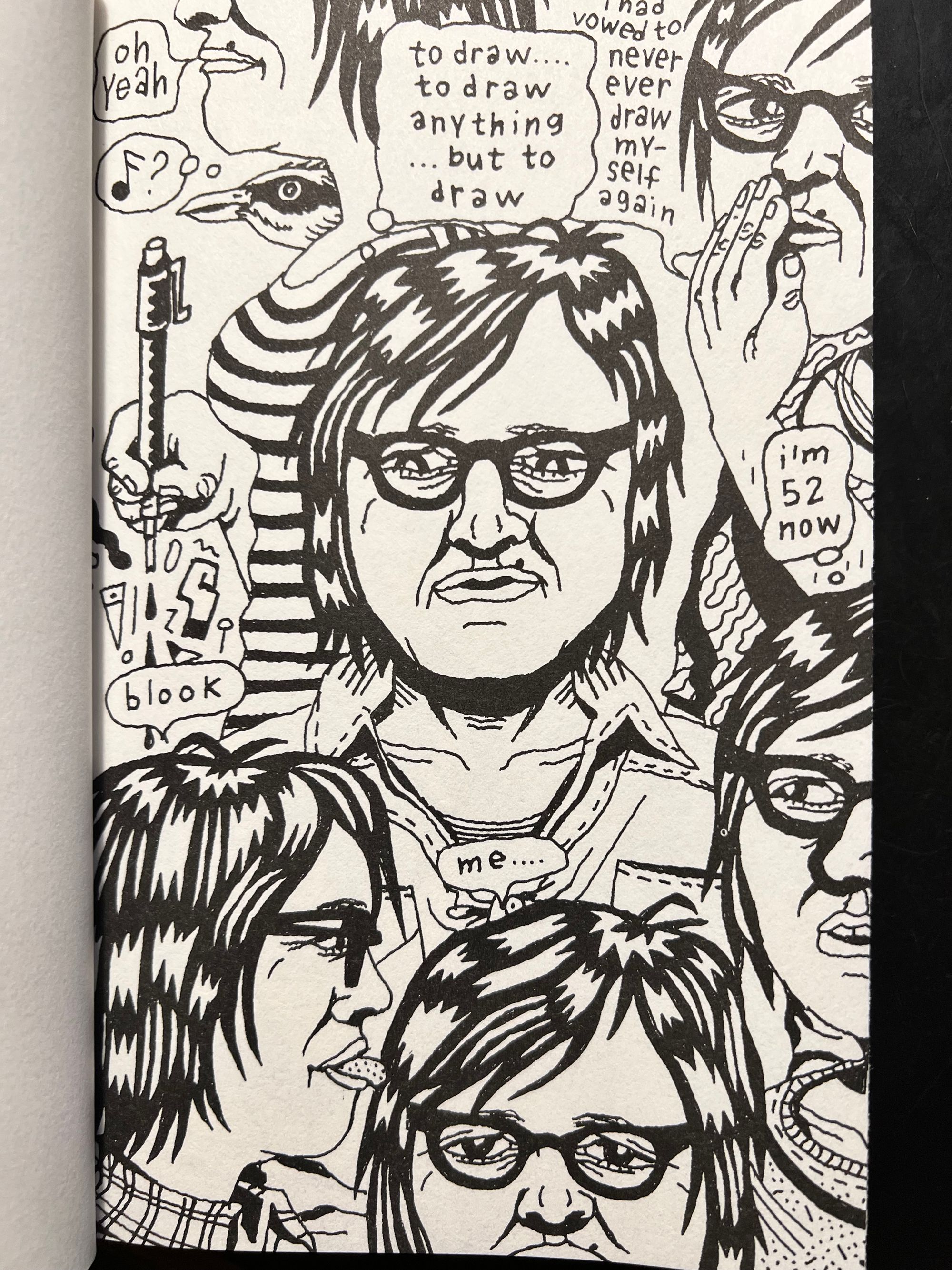

The “story,” as much as there is one, is about a relationship that Doucet was involved in back in 1989, corresponding to a French fan of hers and her comic Dirty Plotte. Eventually, they met in Paris and had a relationship for the brief time that she was there. She tells the reader about the fear, the excitement, the uncertainty, and even the need for that relationship. Strangely for a comic, it’s a story that we experience only through words and no images relative to that story. We just see Doucet telling us the story. She opens the book noting that she had promised herself that she would never draw herself again. Right there on the first page, she states her hesitation about beginning the act of creating this book.

The book begins with being more about the act of creation and the nervousness of opening herself up to an audience again as she used to do in her old comics. Doucet’s entrance into this comic feels almost reckless, starting the story with doubt about what she’s doing. But even before that, the book opens with a strange set of directions: “This book was drawn from bottom to top. Please read accordingly.” So as a reader, you already enter Doucet’s space on a different ground than you normally do with comics. “Top to bottom,” what does that even mean? Flip the page and you’re greeted by a collage of faces, all of them Doucet’s, fretting and procrastinating to avoid making any kind of true progress.

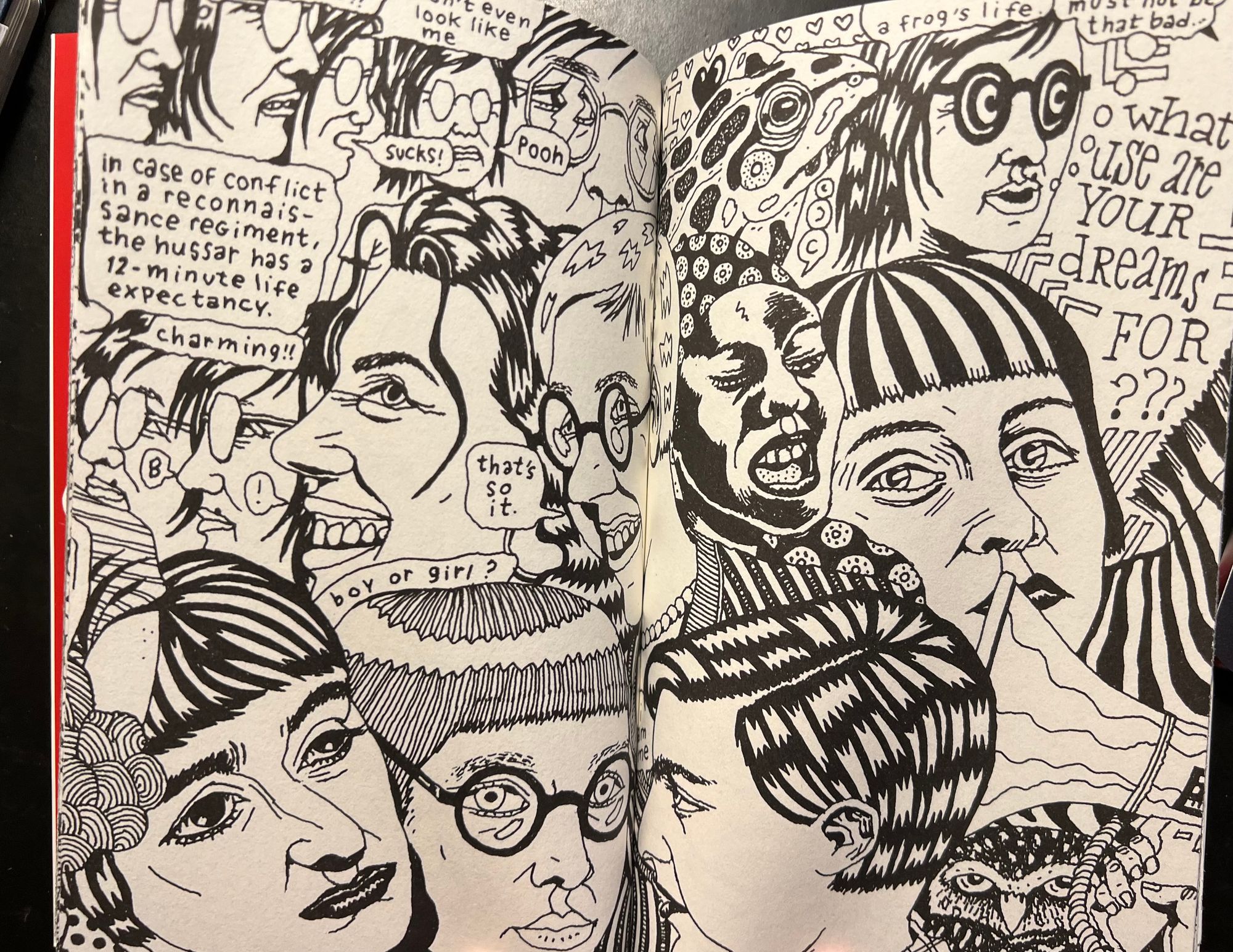

If Doucet is uncertain about drawing a comic again, her composition makes us uncertain about reading her comic, not because it is poorly told but because it is constructed to throw us off balance. Her time away from comics has given her the freedom to just jump back into their creation, rewriting the rules about how she’s going to tell her story. Each page is a sea of faces, Doucet’s and others, that exist outside of the story she’s relating to her audience. Doucet is telling us a story about an old and brief relationship but the other images of this book are a sea of humanity whose only connection to the story is their connection to the space that they are drawn in.

It almost seems like the art and the words are at odds with each other. We’re used to comics where the two work hand in hand, supporting each other and occasionally going to the extreme point that it produces redundant storytelling. You know the type, where the caption or the dialogue just describes what’s happening in the panel. It’s like the artist and the writer don’t trust the other or the reader enough to follow what’s happening.

On the surface of it, Doucet’s words and images have no relationship with each other, existing both in their own narrative spaces and never mixing. And then throw in the fact that you have to read from the bottom of the page to the top and the book is practically daring you to just give up. The humanity of Time Zone J is displayed on every page; you just need to not look past it. The faces in Doucet’s pages are both a background for the story of this love affair while also the story itself. In the images and pages, Doucet shows all of these faces and impressions that cover a wide breadth of humanity, showing how her story is just one small story in the whole world; all of these other faces and people have their own stories that we can only imagine what they are. Her’s is only one of the many stories that could be told in this comic.

Imagine that you’re at a crowded party, stuffed shoulder to shoulder and face to face in a room with all of these different people. Each fascinating face is a possible connection waiting to be made and you’re in that mental space where you’re looking for an opportunity to meet a new and exciting person but you just don’t know where to start. You’re searching for a focal point among all of the sights and sounds that you maybe miss some small details– what’s with all of these birds that just randomly pop up and what’s up with the dolphin that just pops up out of nowhere and then quickly disappears back into the crowd?

But there’s that one voice that you hear over the others and that face that you just can’t escape. Maybe she’s talking to you or maybe she’s talking to someone else at the party and you can’t help but eavesdrop on the private conversation as she tells of youthful indiscretions and choices that she wishes she would have made differently. There are all of these colorful, vibrant, and different people around you but this one woman’s voice and story silence everyone else.

That’s what’s reading Julie Doucet’s Time Zone J is like and it is such a different experience from almost every other comic. Doucet pulls you into this story through the intimacy of the space she creates. Everywhere you turn in this book, Doucet is quite literally there to tell you her story. She traps you in her story and that turns out to be exactly where you want to be, around this captivating person as you try to figure out why she’s so fascinating to you.

Comments ()