“… So Film Me Until My Dying Breath.”- Goodbye, Eri by Tatsuki Fujimoto

Whether it’s to protect himself or his characters, Tatskuki Fujimoto sets up this distance, holding his audience back from being there with these two.

Tatsuki Fujimoto’s latest book Goodbye, Eri functions as a sort of sequel to last year’s Look Back (reviewed here,) thematically picking up from where that book left off. In the earlier book, we got to experience the growth of a great friendship and partnership, watching two young women bond over a love of manga and storytelling until a tragedy cut that relationship short. Fujimoto took us through an emotional rollercoaster in that book. Goodbye, Eri follows a similar pattern— two school-age kids bond over their shared love of movies and their outsider status in school. But the tragedy in this book is there for both kids, Yuta and Eri— one explicitly experiencing it while the other hides it from her friend and the audience.

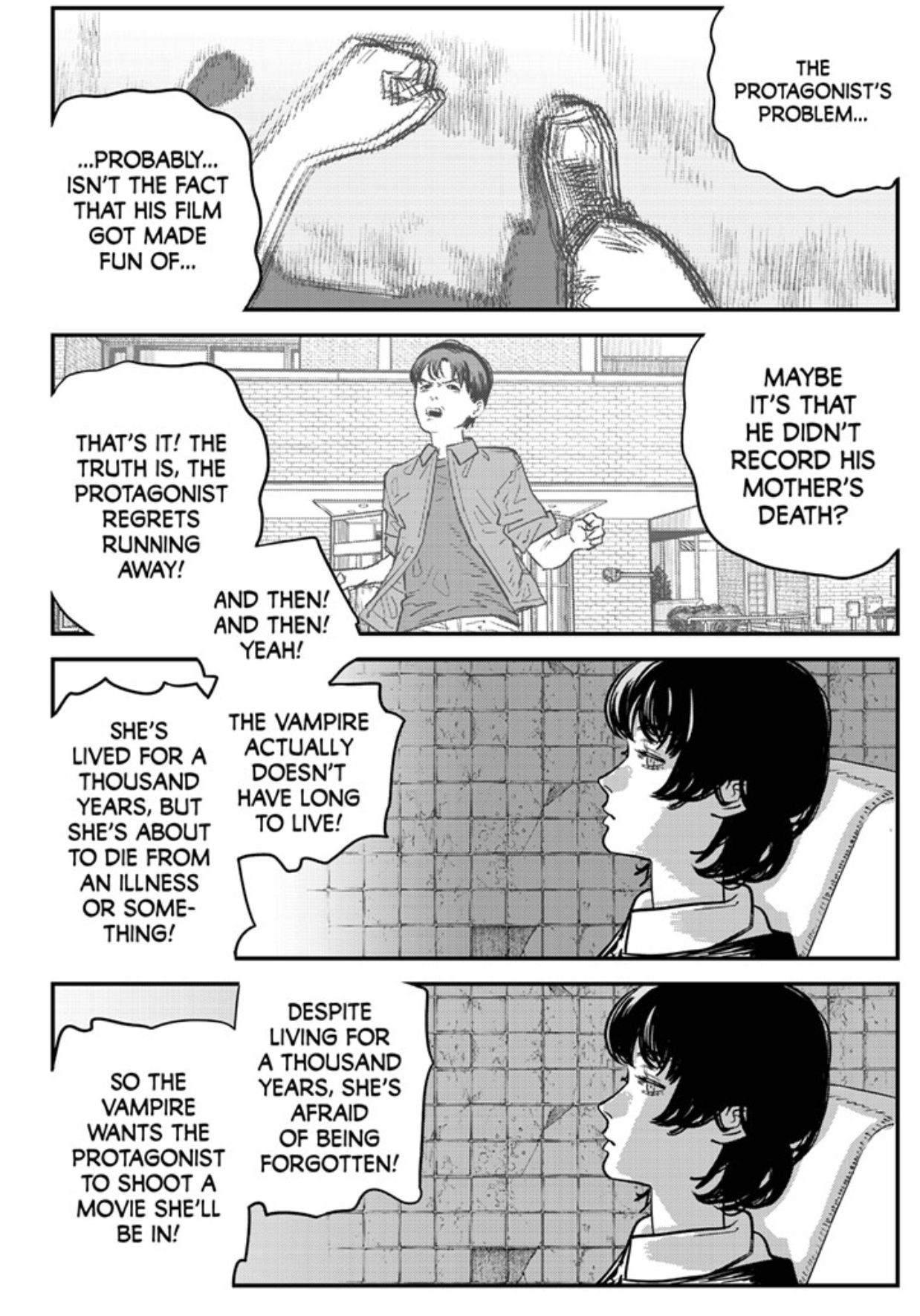

A boy is given a smartphone for his birthday. Yuta is just starting middle school so getting a phone at that age isn’t all that odd. But what is odd is the request that comes with it: his dying mother asks him to start making videos of her with his new phone. “On video, you can hear my voice and see me move,” she says. “That way, even if I’m gone, you can still remember me.” Through his phone’s camera lens, he captures the final days, weeks, and months of his mother’s life, filtered by the love a son has for his mother. After she dies, he takes that footage (about 100 hours of it,) and turns it into a movie to show to his school. But he couldn’t capture it all; when his father told him that this was it and his mother wanted him to film her dying breath, he couldn’t and ran away from the hospital. In his film, which up to this point has been told through his point of view, the pov shifts away from Yuta. We see him running away from the hospital as any child would want to do at that moment just as the hospital behind him blows up. Spectacular special effect explosions punctuate this film that’s about the last days of his mother. Yuta called the film “Dead Explosion Mother.” One of his teachers asks him why did he have an explosion at the end. “That was awesome, right?” is his only answer. His schoolmates are just as puzzled. One girl, whose mother also died in the last year, tells him that she can’t forgive him. Repeating the teacher, she asks “Why’d you add the explosion at the end? That’s the question here.

And that’s only the beginning of the book.

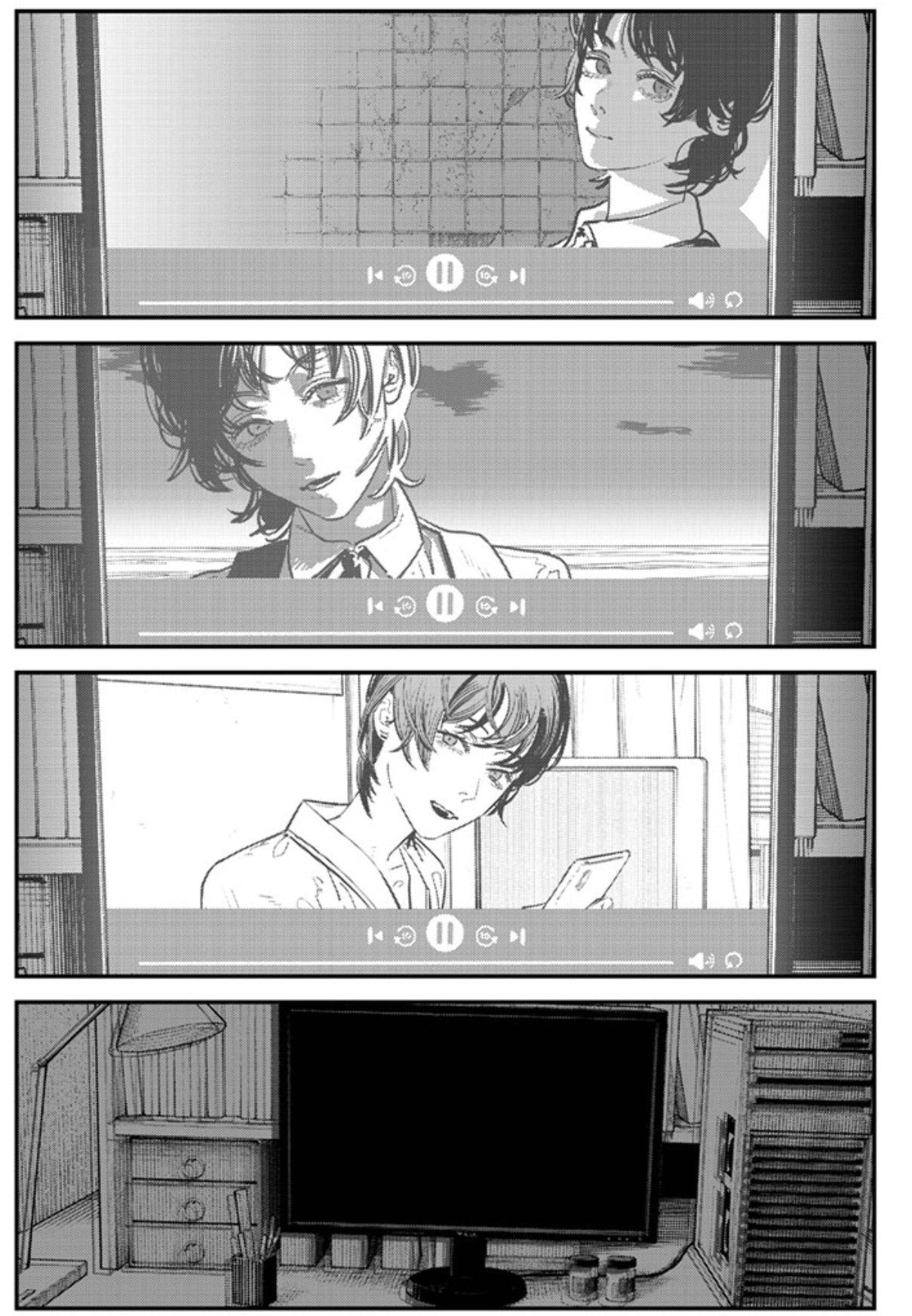

The whole of Goodbye, Eri is told through the screen of Yuta’s phone. Using a fairly static structure (four landscaped panels on most pages,) we’re experiencing this story through Yuta’s eyes and his phone. So when he meets Eri, the one person in his school that connects with “Dead Explosion Mother,” we’re experiencing it in this odd liminal space, removed from the events themselves. We’re watching this as it happens but also watching a movie of the events, distanced from the events themselves. This is what art, whether it’s comics, movies, television, or novels, is- a space between what is and what’s happening next. Yuta’s eyes are our eyes but with the movie and its exploding hospital, he early on establishes himself as a bit of an unreliable narrator. While he may have run away from the hospital as his mother was dying in it, it didn’t blow up like he was in some cool action movie. After his movie is rejected by the school’s audience, he films a suicide note on the stairs leading to the hospital's roof. That’s where he meets Eri and everything changes.

This feels like a very personal story of friendship, sickness, death, and memories but Fujimoto keeps his audience at a distance through the smartphone camera. Look Back was similarly emotionally charged but was much more intimate because Fujimoto placed us in the room with the two young women; we were there with them as they created their stories. The structure of Goodbye, Eri doesn’t allow us that intimacy with Yuta and Eri. They’re often in the same space, watching movies, planning out Yuta’s next one, trying to discover what the story is and it feels like we’re there with them but we’re not. Whether it’s to protect himself or his characters, he sets up this distance, holding his audience back from being there with these two.

We’re constantly viewing Yuta and Eri through the construct of a camera that’s being operated by someone (Fujimoto?) who almost from the start of the story disguises portions of the truth with fiction. Are we watching Yuta and Eri or just a movie about them? Are these events real for the two of them or are they a fiction crafted by someone behind the camera? Fujimoto repeatedly forces us to ask if we’re experiencing these characters or watching these characters. And it’s not that a movie can’t be intimate; it’s more like Fujimoto doesn’t want us to get that close to this story as if he’s protecting his characters in a way that he couldn’t in Look Back.

After seeing Yuta’s film about his mother’s illness and death, Eri helps guide him in making his next movie. She acts as a muse, a dream, a benefactor, and a subject for Yuta’s movie which is about a boy having to process the grief of his mother’s death through the making of a movie. It’s life imitating art imitating life. But this way of dealing with loss through imaginative acts harkens back to the last portion of Look Back, where Fujino fantasizes about a world where she was able to save Kyomoto from a random, deadly attack. Fujimoto is processing something deeply personal in these two books, exploring loss and how we try to contextualize our feelings about it. And he does this through artists and acts of art. It’s looking for ways to protect ourselves from the depths of grief through our ability to create stories about it.

Together, Goodbye, Eri and Look Back have this complicated dialogue going on between them about the ways we experience loss. Goodbye, Eri is more guarded than in the earlier book, keeping some secrets to itself as Fujimoto sets up a WIzard Of Oz-like veil of the camera lens but never quite lets us see what’s behind it. And it’s not to mislead us but to protect himself and his characters. They never become our characters the way that the two in Look Back do. There’s a warmth in that and in Look Back that’s missing from Goodbye, Eri. In the place of warmth, there’s an ambiguous longing for past connections where Fujimoto trusts his audience to understand what’s missing without telling them how they should grieve those losses.

Comments ()