Moving In with Rumiko Takahashi's Maison Ikkoku Volume 1

As the other characters are defined more clearly by their roles in this story, Kyoko remains a mystery to the boarders and the reader. She’s clearly the responsible one in the house but it’s a reluctant responsibility.

Will they or won’t they? It’s a question as old as time.

Or at least as old as romantic sitcoms.

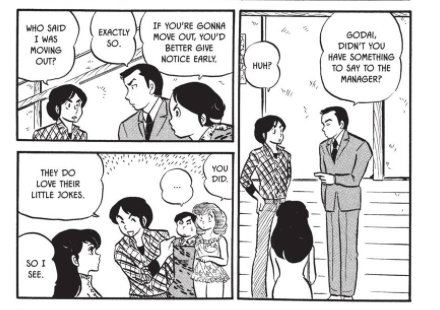

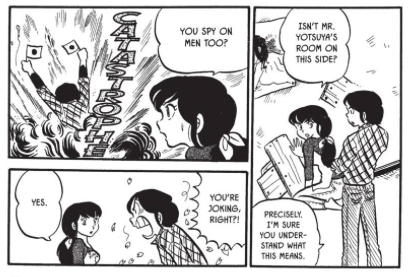

Rumiko Takahashi’s Maison Ikkoku, first published in Japan in 1980, shows us life in a Japanese boarding house where the people living in the house are all up in each other’s business. Godai is a student, half-heartedly studying for his exams. His neighbor Yotsuya (we’re never quite told what he does) uses a hole in the wall between his and Godai’s apartment to get into Godai’s apartment whenever he wants to use another, smaller hole in the opposite wall to spy on Akemi, the bar waitress who has the room on the other side of Godai. Kentaro and his mother also have a room in the house, he the schoolboy who’s a bit too young to understand the context of everything and her the mother-hen of the house who doesn’t do a lot of mothering to the other inhabitants, just more general scolding and judging. Godai plans on leaving the house; it’s a bad study environment for him and the cause of all of his problems. And then Kyoko, the new resident manager, moves in and Godai falls in love at first sight.

The start of Maison Ikkoku isn’t particularly deep or even meaningful. And to say that “Godai falls in love” is probably even exaggerating the point. He falls into lust, infatuated with this beautiful woman who steps into his life without knowing a thing about her or even making the slightest attempt to get to know her before letting his attraction to Kyoko take over his life. But it’s all played for comedy so it’s alright, isn’t it? Takahashi’s screwball antics set a lively and not-quite-so-serious tone for the book that it mostly follows. The residents of Ikkoku House are a typical dysfunctional family, one that occasionally lewdly spies on each other through holes in the wall. Even Kentaro’s mother, the responsible “adult” of this group, acts more like a petulant kid, fed up with and maybe even slightly jealous of the other’s youth. She almost lives vicariously through Godai, Akemi, and Yotsuya.

From the moment she walks in the door, Kyoko is something different and new for this group. By the time the story opens, the previous resident manager has already fled the scene, quitting because of easily understandable exhaustion. From the first few pages, it’s easy to see what could have driven him to that point as the residents of the house act far more childish and immature than you would think functioning adults would. They bicker, tease, and spy on each other, creating an environment that screams more frat house than boarding house. If the previous house manager thought he was just going to be a landlord or apartment manager, he found himself in the middle of a bunch of immature children playing at being adults. And then in walks Kyoko, the new house manager with her own secret past, looking for an opportunity to bury herself into being the responsible one. If only she knew what she was getting herself into.

Unlike the other inhabitants of the house, Kyoko has surprising depth to her. As the other characters are defined more clearly by their roles in this story, Kyoko remains a mystery to the boarders and the reader. She’s clearly the responsible one in the house but it’s a reluctant responsibility. Moving in with her dog Soichiro, Kyoko is the only one of these people who has a past. She’s the only one who has a life before the beginning of the book. It’s a simple thing but Takahashi has this woman who disrupts life in the house, especially for Godai, who is more than just an object of obsession, even if that’s how she is introduced.

Entering the manga as an object of desire, Takahashi slowly develops Kyoko, giving her a history and a family that no one else in the house has. Godai is a clown that you feel somewhat sorry for in his travails. You can feel sorry for him and at the same time definitely feel sympathy for Kyoko but everyone else in this book exists only to vex Godai and Kyoko. Godai is driven by a lust for Kyoko, one that’s barely interested in getting to know her. It’s sad to watch this man stumble over his own tongue as he’s driven by an unexamined attraction to her. She’s pretty so that’s why he wants her after he first sees her.

Kyoko and Godai are the two characters in this book shown with some depth, which makes sense because it’s their stories. Takahashi has all of the other characters around them to add color and a bit more personality to the story but they all exist to fill in a comedic role. As she draws them, they never waver in their purpose in the story. All of them are obstacles between Godai and Kyoko. They fill in the space so that Takahashi can concentrate on showing the frustration, the attraction, and the fumbling of the pair.

When another “suitor” enters the picture, a tennis instructor who displays a tad more true interest in Kyoko, it just fuels Godai’s competitive spirit. Coach Mitaka seems like a nice, decent guy in this story even if Takahashi gives him a few insecurities that the story has fun with. He’s not that much of a developed character but he shows a bit more depth than Godai does, enough depth that it’s hard to figure out why Kyoko continues to show any glimmer of interest in Godai.

But before Mitaka enters the picture, the first half of this book centers on Godai, his struggles with his school exams, and his desire for Kyoko. Takahashi plays this for fun comedy and largely delivers an enjoyable, if somewhat inexplicable, romcom. And that’s purely based on the charms of her story. Godai is a “lovable” loser. At least, that’s how the story tries to position him as his late-night, drunken pronouncements of his “love” and his rivalry with Mitaka positions Kyoko as a prize to be won. Takahashi gives Kyoko enough agency and purpose to be her character but at times it feels like she’s in a different comic than the rest of the cast of this comic.

Everyone but Kyoko piles on Godai. He is our “hero,” but just at the beginning of his heroes’ journey even if he doesn’t quite live up to the tasks before him. Too easily distracted by the world around him, Godai flutters from moment to moment following any shiny thing in front of him. In the second half of the book, Kyoko becomes more of the central character, given an explored life outside of the confines of the house she manages. As we get to learn more about her life, she becomes a tragic figure, a widow at a young age who is conflicted about how she should live after the death of her husband. She wants to withdraw to remain faithful to her dead husband but is that really what she should do? Is that the best thing for her?

Takahashi has a wonderful playfulness with her characters that animates them. Whether it’s the neighbor who sneaks into Godai’s room through a hole in the wall, the waitress neighbor who mercilessly taunts Godai, the older neighbor and her young son who just generally try to annoy Godai, Takahashi plays these characters off of one another, delivery a fun, slightly mean-spirited playfulness in this house. As they exist just to play a defined part in this story, they provide enough comic relief to distract you a bit from the drama of the story. Takahashi has a good time with her cast, finding laughs in the different ways that they torment Godai and Kyoko and their possibly burgeoning relationship.

With one of Rumiko Takahashi’s first comics, Maison Ikkoku V1 establishes a fun rom-com dynamic where she lets the characters and personalities of her cast drive both the humor and the drama. Even if the supporting characters are a bit shallow, Takahashi’s Kyoko is a fascinating woman with a past who needs healing that this house that she’s managing may be incapable of providing. This book provides a lot of setup but also gets into Godai and Kyoko’s story, allowing both of them the opportunity to change a bit from the opening pages through to the end of this volume.

Comments ()