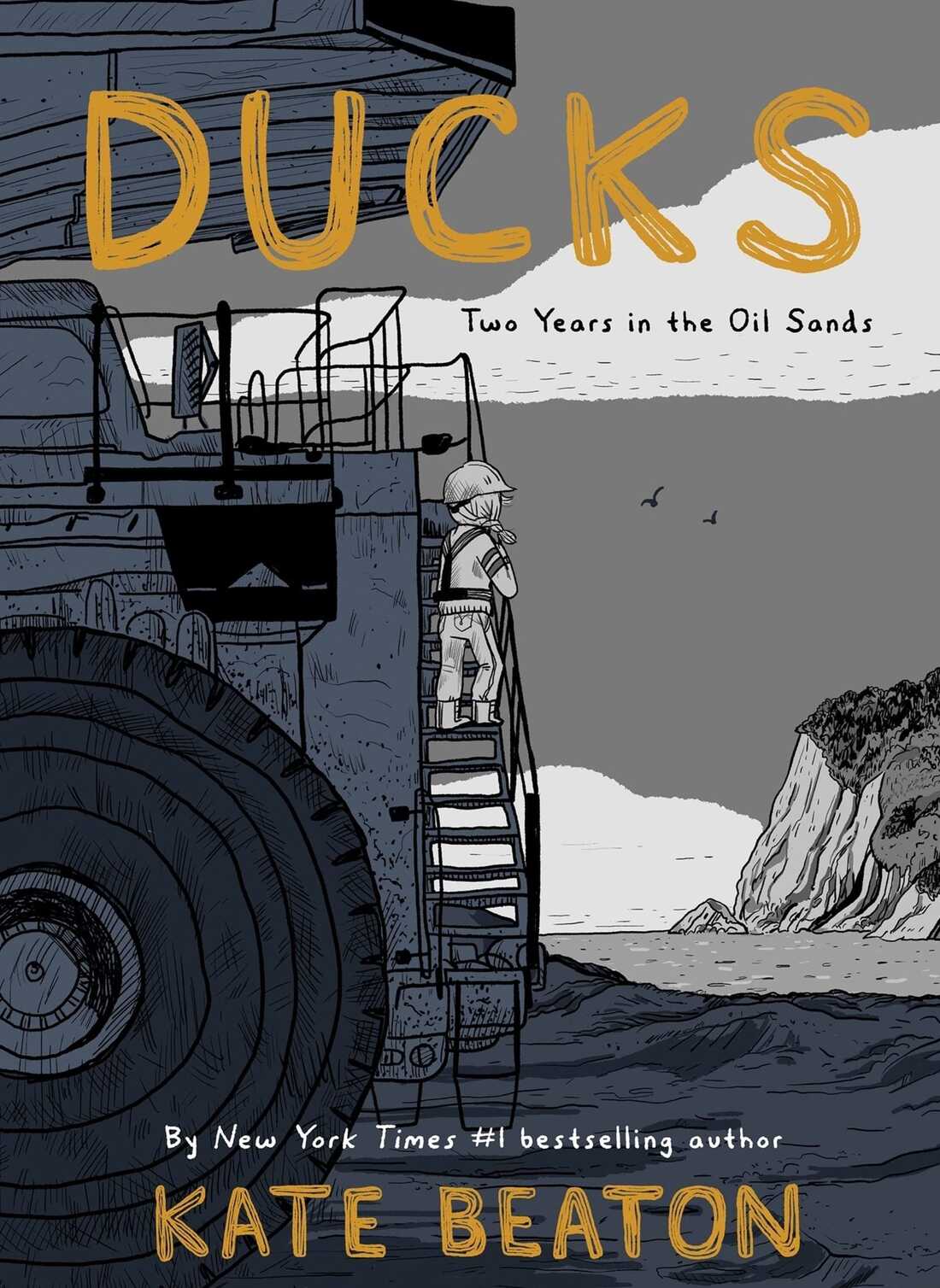

Ducks: Two Years In the Oil Sands by Kate Beaton

Kate Beaton is giving us this insight into Kate’s story that she and the people in her life at the time don’t have. And the cruelty is that we’re even less capable of nurturing or protecting Kate than the people and systems that are part of her life.

There’s an active system in Kate Beaton’s Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands that’s designed to exploit its workers. There are many systems on display that look for ways to game both the work and the workers. These systems operate on a personal level, a gender level, a financial level, an ecological level, and even a socio-political level. In Ducks, Beaton revisits 2005, the time in her life just after she graduated from university and faced all of the student loans that she needed to get an art degree. That’s one system, an educational system that requires most people to leverage a large chunk of their future earnings to pay for it. And for North America, it’s a fairly common systematic exploitation; to get a job, you need a college degree- to get a college degree, you need a job to pay for it. And in many ways, it’s the most insidious system at play here as it is what makes Kate explore and have to engage in several other systems that have been corrupted over time to tear down people instead of building them up.

For Kate, all of these satellite systems orbit the system of work, or more specifically, of employment. To pay for that university education, Kate travels from the east coast of Canada to Alberta and its oil sands. There’s work to be found in Fort McMurray, one of the main settlements built up around the oil business. Many Canadians have found themselves in the same situation as Kate, needing to find ways to pay for an education and heading west for a couple of years to make some good money to get out of debt before beginning their true vocation, hopefully, debt free. So here’s a structured system that’s designed to attract young people to work on the sites, in the offices, and in support roles of big oil. And it’s a system that Kate enters into, seemingly understanding the mutual benefits to both parties- the employers and the employees.

In many ways, the work is just work- a contract entered into in which services are paid for with wages. But it almost feels cliche and condescending to say that these oil sands are no place for a young woman. And that’s less because of the work itself than it is about all of the other systems at their exploitative work. And that’s not to say that the oil sands are for young men; these systems have formed to eat at men and women, old and young. Beaton focuses on her experiences, what she did and what was done to her, but she develops other characters, mostly her close co-workers, so that we get glimpses into their experiences too, what brought them to Alberta and what has worn them down over time. Some are the same issues that Kate faces; some are different.

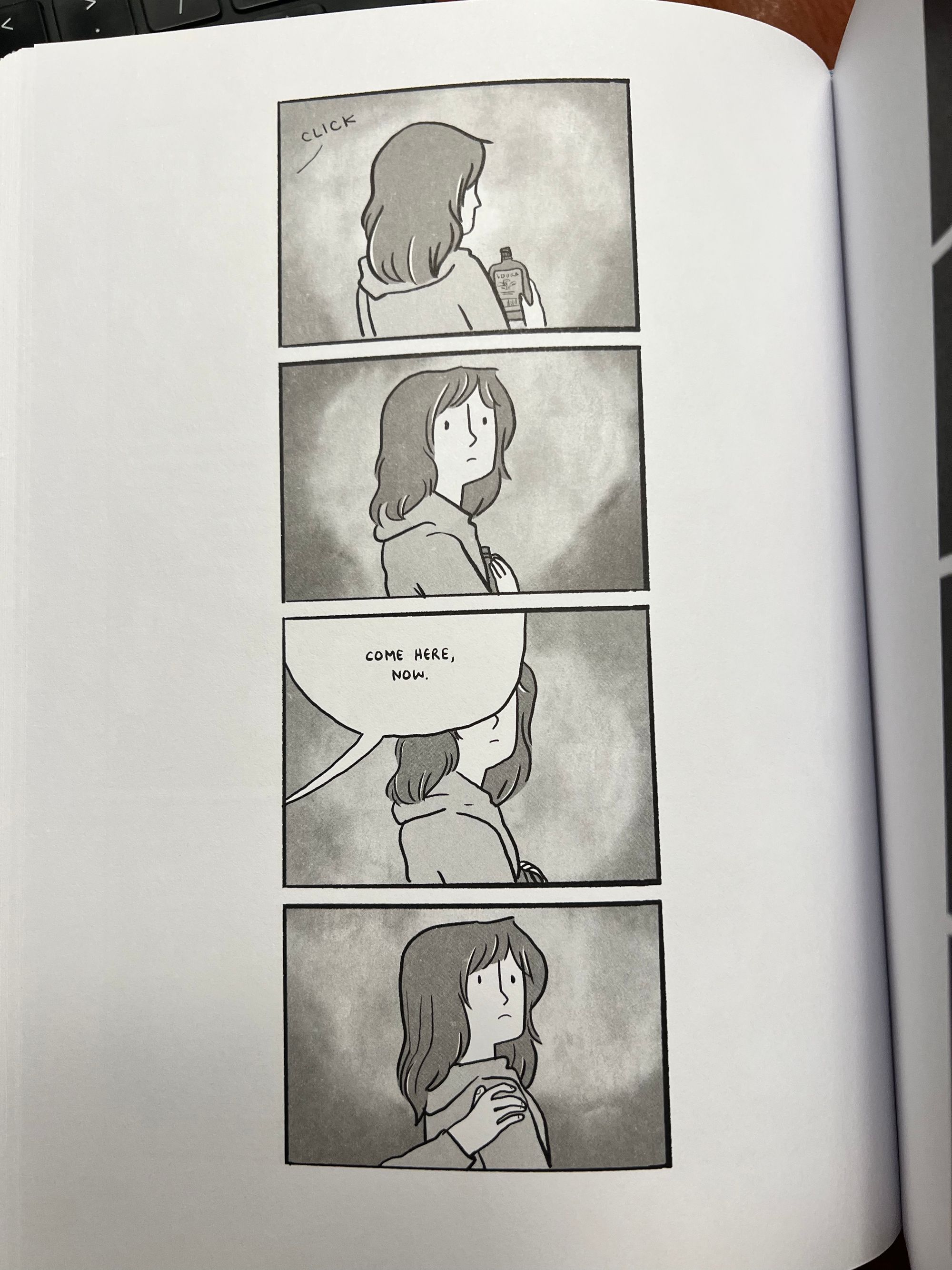

Ducks is primarily built around people talking and developing relationships, good and bad. Beaton tells it mostly through medium-focused images; there are not a lot of close-ups or far shots in her drawings. She uses some wide images to capture her settings but when she shows Kate at work, talking and helping out people, it’s in this fairly steady frame design to focus us on the characters’ interactions. It also acts to ground the reader in her story. For much of this book, Beaton frames us as quiet eavesdroppers into her life.

It’s like we’re largely in the corner of the room, just off-panel but still silently witnessing Kate’s life. It’s an uncomfortable position for us to be in; it’s hard to watch what happens around her and to her and not be able to act. There’s powerlessness reading this book (another system acting on us?) that probably mirrors a lot of what Kate was feeling at the time. We’re swept up in these events, carried along by the need to find out how it ends without ever being able to act or to help out in situations where we can recognize that Kate needs someone to be there for her.

Kate is put into all of these situations, from the uncomfortable to the personally destructive. The ways that Beaton frames each encounter puts it front and center where we can’t ignore it, from the basic inequality of the work to the sexism she encounters, to the abuse that’s done to her. It’s two years of her life where she experiences the worst that humanity has to offer and we’re experiencing it with her. Sure, we could put the book down and grab something more fun and light but as Beaton makes us confront these things from her life, she’s building our investment in Kate, in the strength and resilience that she develops. Beaton is giving us this insight into Kate’s story that she and the people in her life at the time don’t have. And the cruelty is that we’re even less capable of nurturing or protecting Kate than the people and systems that are part of her life.

It should all be better than this.

We should be better than this.

We watch all of these powerful and abusive systems attack Kate physically and emotionally. It’s probably only a small portion of what she experienced but Beaton transfers her pain and frustrations with the system to us. It’s amazing how she makes us both a witness and also a recipient of what we’re reading. This autobiography is a painful page-turner, painful in an empathic way but also a page-turner as we see her persevere through all of this. But even the last pages show that those experiences are still there outside of Alberta’s oil sands. That may be part of the reason for this book, to try to work through the damage those systems did, or even just to offload a portion of it on the audience. Hopefully, we can take a portion of Benton’s pain from this time, giving her some relief by sharing the pain with her.

It’s easy for an autobiography to tell you the story of a life. It’s another thing for an autobiography to get you to live that life through its story. Beaton places us by her side during these two years of her life, witnessing and taking part in these systems that have been twisted over time to wear down our personhood and to make us just another cog of those systems. All these years later, Ducks: Two Years in the Oil Sands fights back at these systems, denying them the final say in who and what Beaton became after her time at work in an environment that cares little for the people working to maintain it.

Comments ()