It's the End of the World-- a look at Naoki Urasawa's 20th Century Boys

It’s weirdly prophetic to read 20th Century Boys in 2024, looking back on the last decade and wondering how we missed Urasawa’s possible warning of all of this.

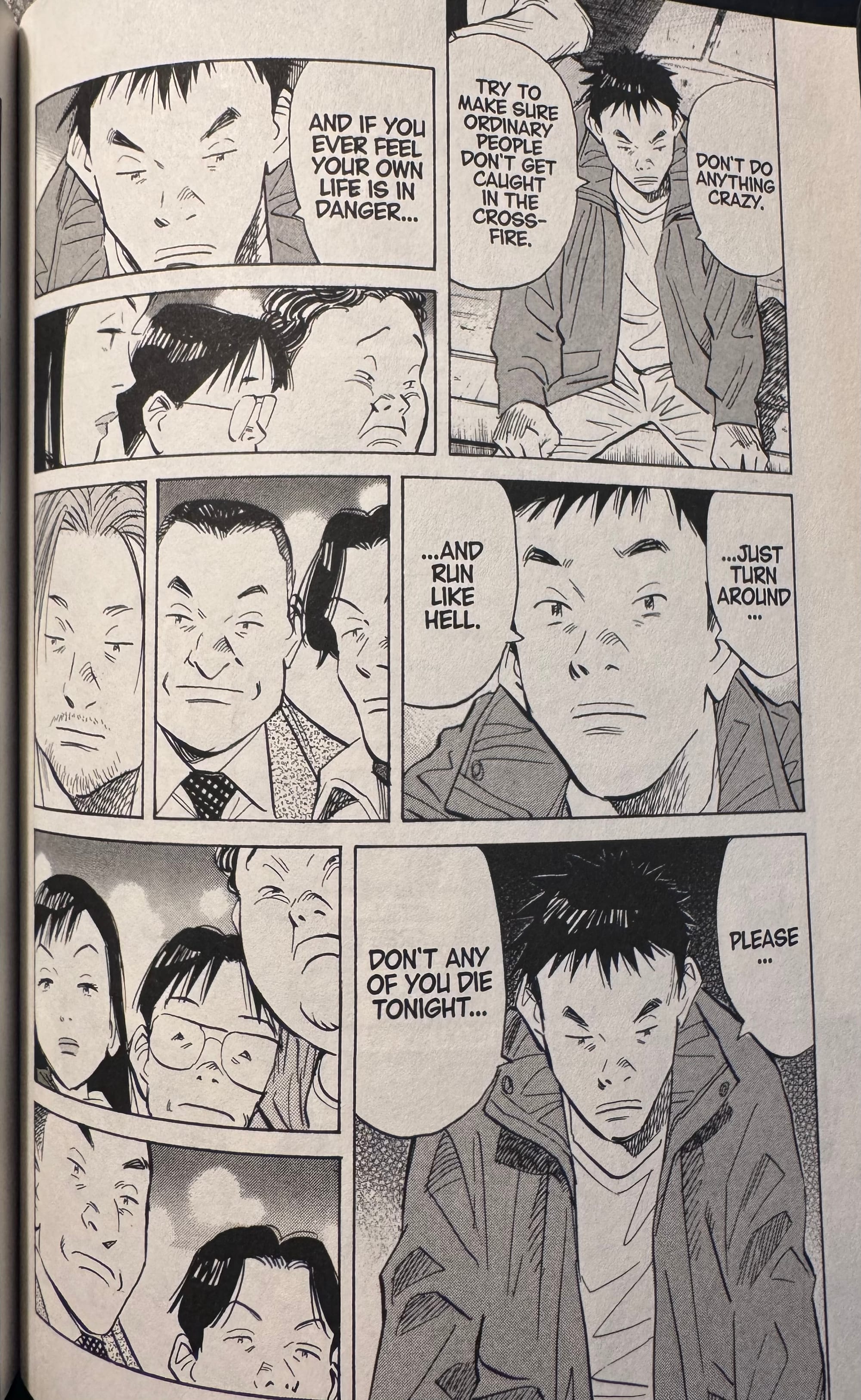

“If you ever feel your own life is in danger… just turn around… and run like hell. Please… don’t any of you die tonight.” Kenji, Dec. 31, 2000.

Naoki Urasawa’s 20th Century Boys is the story of a bunch of 1970s kids who grew up to ruin the world. And they started out just doing what kids do— they formed friendships with the kids that they liked and just kind of ignored the other kids in their grade. Most of us would just call that elementary school but to Urasawa, it’s the root of everything we do with our lives from then on. Those childhood days, the decisions we make, the things and people we ignore, and the bonds we form stay with us through our whole lives, for better or for worse, even as people move in and out of our lives. These things echo from our youth into our 20s, 30s, 40s, 50s, and beyond, the unseen chains of our childhoods that drag behind us.

Urasawa’s story begins in 1970, with a rebellious Kenji Endo sneaking into the school office and blasting T. Rex’s 20th Century Boys over the PA system, hoping with that one action to change the world. It’s this optimism that you can change the world through music that carries Urasawa through this whole story as Kenji finds successes and failures through his own musical aspirations. Urasawa uses rock and roll, to chart where Kenji is in his life. Rock and roll, particularly one of Kenji’s songs called Bob Lennon, becomes a touchstone throughout this series, one that Kenji and his niece Kanna use to remember themselves and to remember how the world should be. It’s an anchor to a better time, which exists both in the past and in the future. It’s hope in a world and a story that needs it.

Naoki Urasawa performs Bob Lennon at the Japan Expo 2012

But Urasawa’s tale is an end-of-the-world story as the villain, the so-called Friend who has mysterious ties to Kenji’s childhood and family, is out to either rule the world or to burn it to the ground. A terrorist attack on Japan on December 31st, 2000, Bloody New Year’s Eve, by a giant robot sets the Friend up to be the savior of the approaching 21st century. That act sets the Friend up to be the hero and Kenji and his friends to be the villains, at least in the public’s eyes. Throughout the series, you see all of these groups come together to fight the Friend. It starts with Kenji and his childhood friends in 2000 but over the next 18 years, this group splinters off into several different offshoots, all with ties to Kenji but each fighting and rebelling against the Friend in their own ways. Urasawa develops these groups and communities that reflect the bonds Kenji and his childhood friends had. Even when Kenji disappears for over fifteen years, just vanishing after that New Year’s Eve attack, he’s never far from the hearts of the people who mean something to him, his niece, his friends, or even people who just hear the legend of Kenji Endo.

Urasawa began this story in 1999 and didn’t finish it until 10 years later. Reading it in 2023, there’s a lot to look at and wonder just what did Urasawa see in the world all those years ago. Starting with the fin de siècle paranoia of the time, saying goodbye to the 20th century and stepping into the future, Urasawa taps into the trepidation that ran through the world back in 1999 (more Y2K fear in the United States but still being trapped in a liminal time between centuries.). He could probably see all that in the world around him when he began telling this story. But could he have seen the rise of a demagogue in the world, a world leader who fed on the desires and prejudices of a society? What about a pandemic that spread rapidly over the world, changing life as we know it? Or a giant wall built to divide countries (in this case Japan) to control who gets in and who doesn’t? Urasawa saw all of this as being a possibility years before Trump or COVID-19 but so many elements of this series that seemed like fiction once now read as a reflection of our current world. It’s weirdly prophetic to read 20th Century Boys in 2024, looking back on the last decade and wondering how we missed Urasawa’s possible warning of all of this.

Ultimately this series isn't a prophecy. It isn’t warning us of a future of false leaders or worldwide illness even though those elements are there. But maybe it is a warning of the divisions and isolation that we’ve experienced because of those things. For many of us, the world seems smaller than it was four or eight years ago. It’s more lonely as we’ve experienced mostly conflict, division, and isolation for almost a decade now. Urasawa is a great storyteller; every character, no matter how seemingly insignificant, has their own story within this larger story, and somehow or another, they all trace back to Kenji, his friends, and their childhood. It’s from that childhood starting point that we follow seemingly small slights that turn into decades of pain, oppression, and fear.

That’s a lot to take in; 20th Century Boys can seem daunting (and that’s before you even realize that after many volumes, the series’ title changes to 21st Century Boys and there’s even more that you need to read.). All of these characters come into and move out of this story at different phases of their life, over 20 years. Urasawa juggles the scope of this story by never making his storytelling too dense; there’s room for all of these characters and story ideas because Urasawa creates the narrative space for this large story. He allows it to live, expand, and contract as the story requires it to. So when he leaves one plot thread dangling in Tokyo to suddenly jump to Germany to bring in new characters, you don’t feel lost or even anxious to get back to the previous thread because Urasawa has created the room for this story to have all of these tangents and offshoots that still come back to the central themes and plots of his story.

At various points throughout the story, when Kenji or Kanna are about to lead their comrades into battle with the Friend, they don’t deliver a “give me liberty or give me death” speech. They tell their friends, their family, and their soldiers “If you ever feel your own life is in danger… run like hell.” On one level, the stakes of 20th Century Boys is the whole world but that almost seems like a secondary one to making sure that all of these people and friendships survive. Kanna views her uncle Kenji as a hero and the legend of Endo Kenji builds that up but the story here is not about winning- it’s about surviving. It’s about being alive when the fighting is over to be who you once were and can be again. As much as Kenji is fighting the Friend to save the world, he’s fighting for the life that he wants. That’s what Kanna is doing as well even if she doesn’t know what a life without fighting the Friend is like. She remembers her uncle and to her, that’s the promise of what life should be.

Comments ()