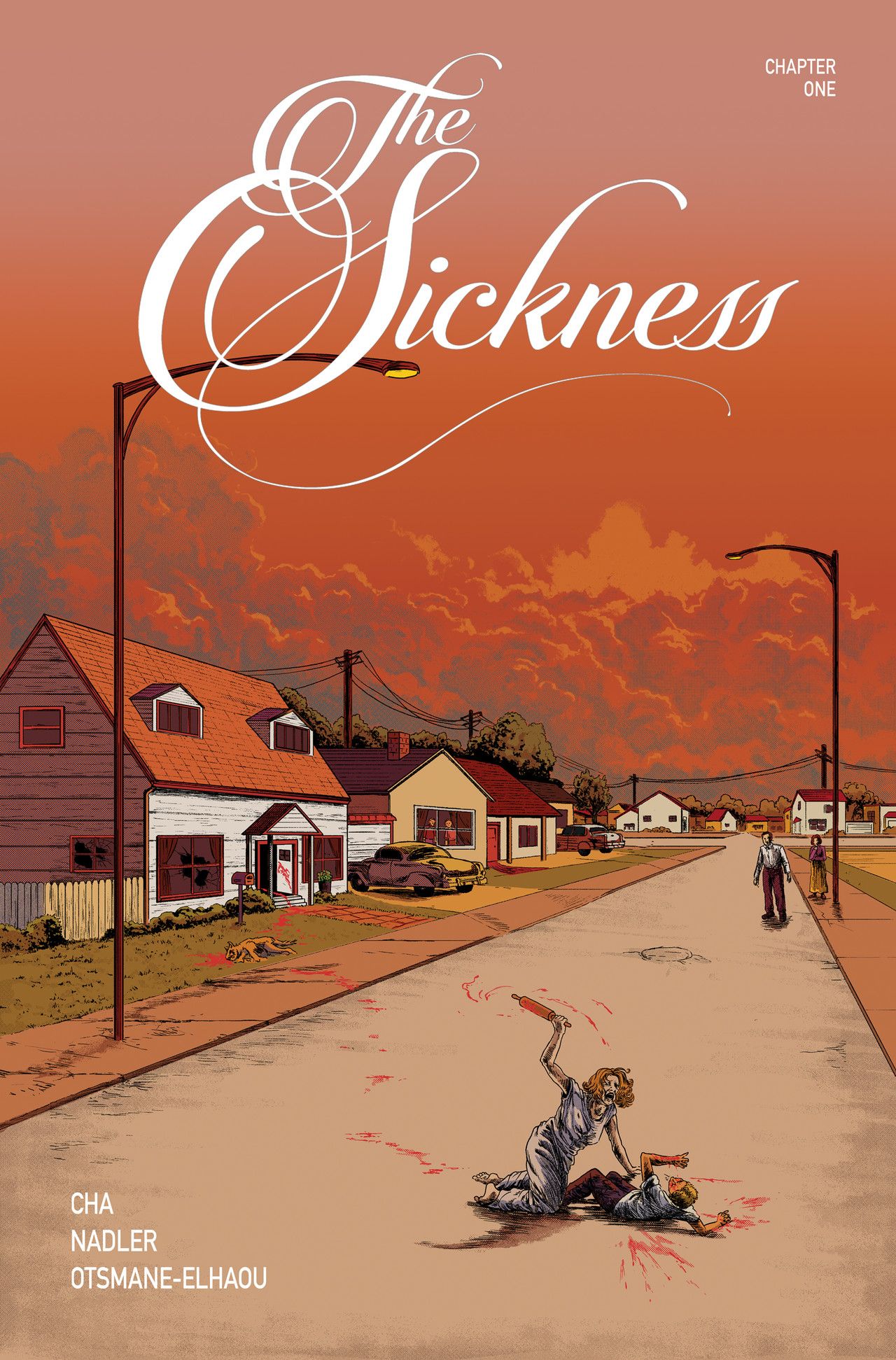

Learning To See the Unseen in Jenna Cha and Lonnie Nadler's The Sickness Chapter One

Jenna Cha creates a realism in the things that we can’t see.

“I don’t know… Maybe the world shakes different now. There are things hiding in the air, waiting to come alive.”

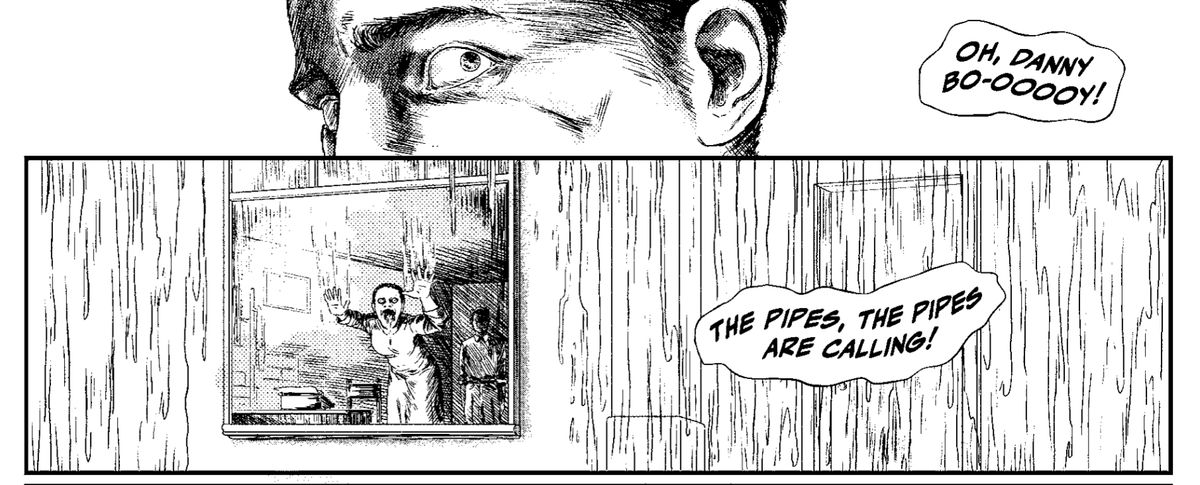

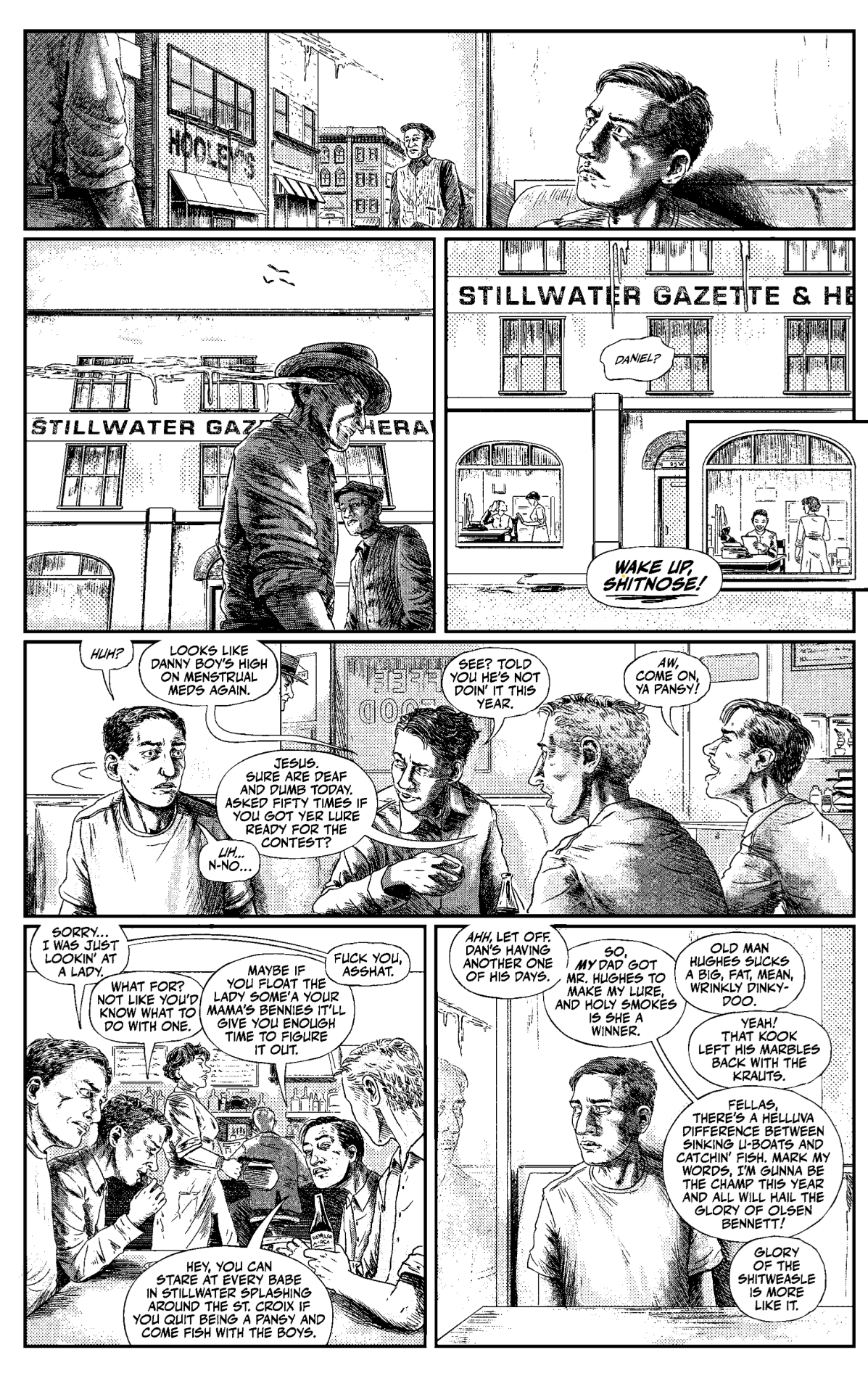

In Jenna Cha’s artwork in The Sickness, Chapter One, something is happening in it that we can’t see. It’s just outside of our sight; maybe it’s happening on a different frequency than our vision can adjust to or it’s something that our brains are trained to filter out of our perceptions for the sake of our own sanity. Set in Minnesota in 1945 and Colorado in 1955, Cha and writer Lonnie Nadler’s first issue constantly hints at things that most of us can’t see. Whether it’s Danny, sitting in an Indiana diner, so focused on the building across the street and its windows which don’t provide anything more than a surface glimpse into what’s happening in the building, or a Colorado mother who saw things in and on her family before she took an ax to them, Cha and Nadler lay the groundwork of unseen horrors. Dale, the son who somehow survives the brutal, murderous attack by his mother, describes her visions from this hospital bed; “Mom… she… she said there were… holes everywhere. And bumps and… teeth and… she said they were crawling on me,” and then adds “… and she kept saying there was someone else in the house.”

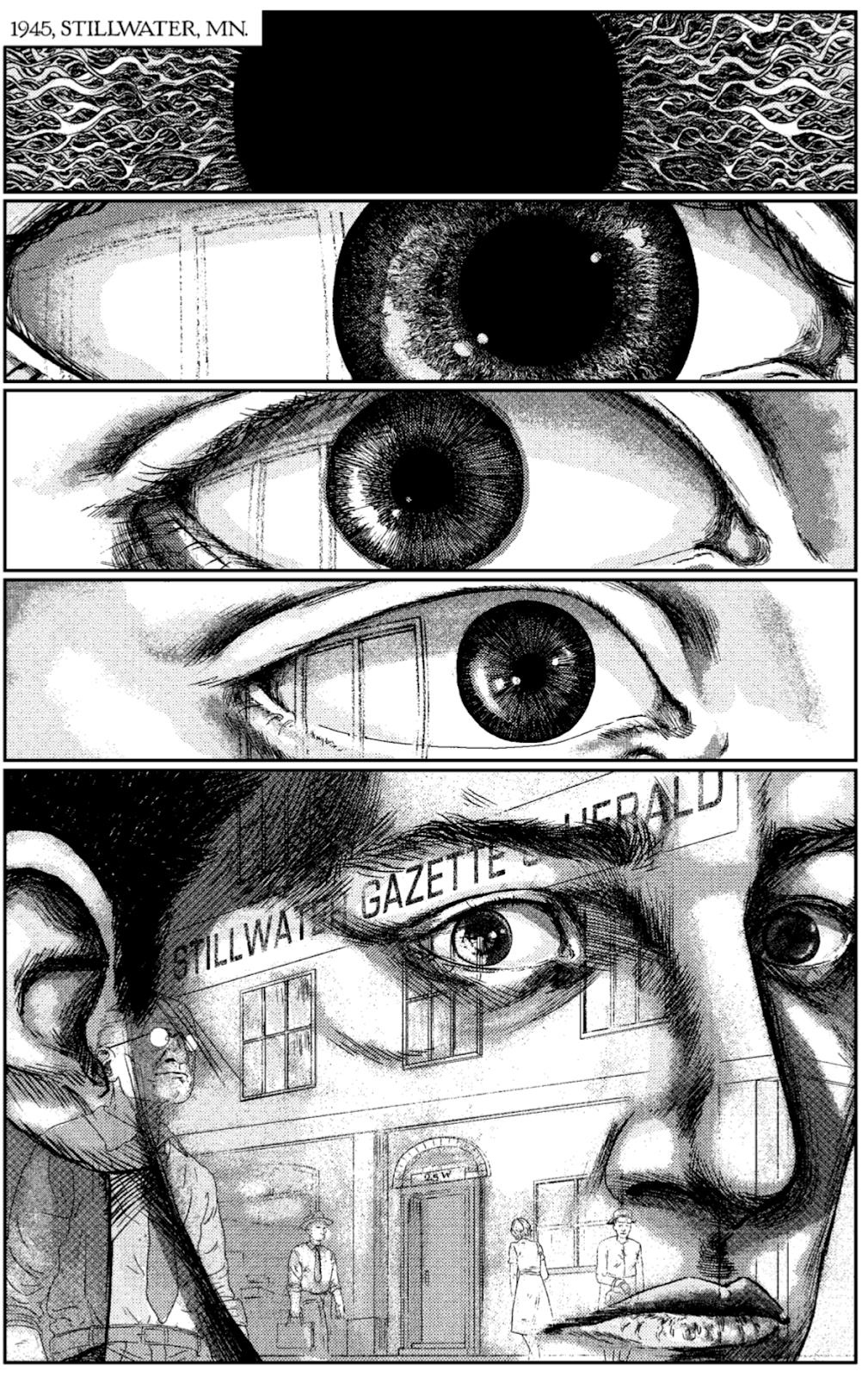

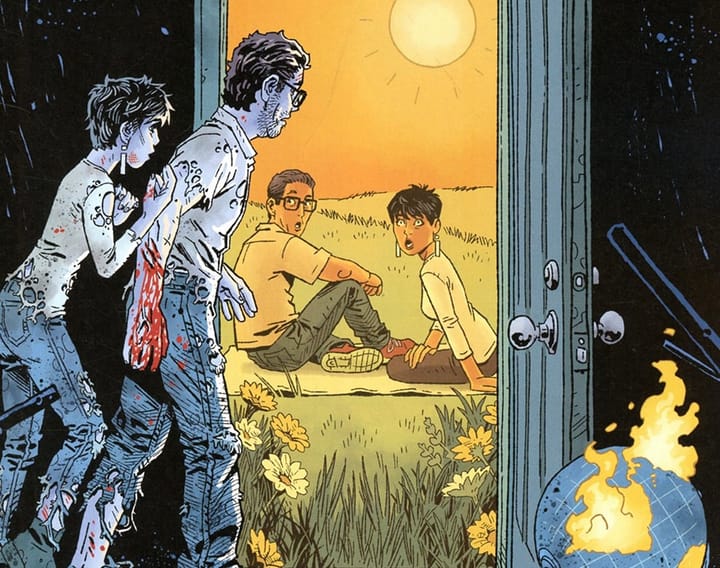

Danny and Dale’s mother’s perceptions function on a level that ours simply can’t at the start of this story. Cha lays in these brief and shocking moments where our perceptions start to match theirs, as we see people with their eyes as if we’re adjusting to this new reality. We see the holes, the bumps, and the madness as if the narrative is rewiring our brains to align with these characters. The Sickness Chapter One isn’t trying to exist in our world; it’s pulling us into its world. This world looks and feels a lot like ours; it’s recognizable and easy to mistake for the real world. But on the first page, Cha and Nadler are already taking us outside of the norm.

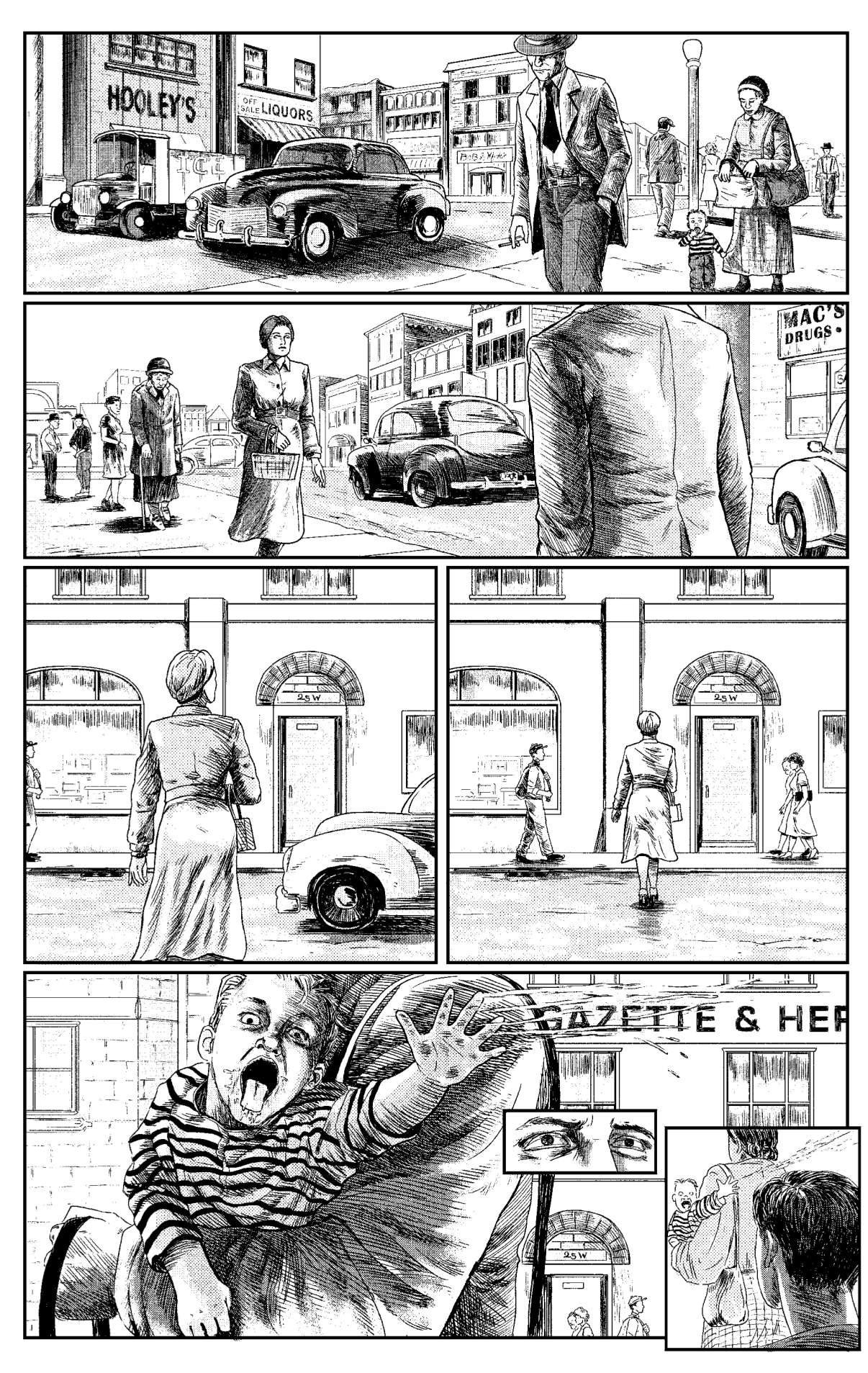

The issue opens with an extreme closeup of an eye and then slowly pulls out over 4 more panels to reveal Danny’s face, overlaid with the building that he’s watching from across the street. We move from an extremely internal state of being to a state that’s in tension between the internal and external. This is the beginning of the readjustment that Cha and Nadler are performing on our perceptions, trying to force us into a kind of synchronicity with the narrative before ejecting us from it by placing us on a seemingly normal street, with four panels of relative normality, circa 1945.

But then there’s that kid, doing what a kid does, probably looking at his reflection in the window, unaware of his appearance to anyone on the other side of the diner’s window. There’s nothing sinister in the action but everything sinister in the timing of it. This is how Cha and Nadler keep us riveted to the story, by being so vivid in their depiction of 1945 that we’re looking for the shadows obscuring what we can’t see. In these moments, there’s a literalness to Cha’s artwork that makes it difficult to look away from them. She creates a realism in the things that we can’t see.

That’s what makes The Sickness Chapter One so much more suspenseful. We can immediately sense through the art that there’s a reality these characters can see that we can’t. Cha and Nadler then show us that only Danny is tuned into whatever exists outside of our sight; his friends chide him and laugh at him in the cruel way that friends can, also unable to catch a glimpse of what he sees and what haunts him. Only Danny can see it but slowly our perceptions start to line up with his and that’s maybe the scariest thing in this issue as we can begin to see the world behind the world here. So when the story jumps 10 years and half a country away in the second half of the issue, maybe we begin to understand what a suburban housewife sees, the holes and the bumps and the teeth crawling on people.

There’s no place for the reader to hide in this story. Whether it’s Minnesota in 1945 or Colorado in 1955, there’s this disease that permeates these times and these places. Jenna Cha and Lonnie Nadler maybe aren’t carriers of this disease but they are practitioners of it, using this comic to turn it into a viral system that’s just starting to worm its way into our consciousnesses.

Comments ()