Poison Ivy: The Virtuous Cycle - A Dark and Complex Journey of Revenge and Redemption

Poison Ivy has lost something and this trip is her attempt to regain it. It’s more than just her powers that are lost; it’s her direction.

Up front, let’s establish a bit of honesty— Pamela Isley, more commonly known as the Batman rogue Poison Ivy, is a monster. Not in the literal sense that she turns into some monstrous creature but in that she’s a monstrous person in G. Willow Wilson and Marcio Takara’s Poison Ivy: The Virtuous Cycle. This book, the first in a new series, actually reads more like it’s the beginning of the last season of a prestige television show, where we’re spent years watching a deeply flawed anti-hero try to hold everything together to reach their goals even as the world and the law close in around them. Their days are numbered; it’s not a question of how it will end but how badly will it end. It’s Walter White thinking that he’s conquered the world even as more dangerous and more evil forces than he toy with him as if he’s their plaything. That’s the opening of this book as it builds off of some Batman event or DC crossover but Wilson and Takara deftly slide by all of that, using it as the setup to give us some clues to Ivy’s headspace without requiring us to get into the details of stuff that we probably don’t want to know.

Having been mostly depowered in whatever happened in the past, Isley begins a road trip out to the west coast to try to find the one person who can help her regain her lost glory. But Wilson and Takara quickly establish that this trip is more than just a journey to reconnect with someone from Isley’s past, trying to recreate some magic that’s been lost— this is a revenge story where Isley plans to scorch the earth behind her, killing the humanity that’s ravaged the nature that she’s been so intimately tied to in the past. Wilson writes Ivy as a pure anti-hero; she may be our protagonist and written from a sympathetic point of view but from nearly any other perspective, she’s the rough beast slowly slouching towards the west coast with a righteous anger pushing her forward.

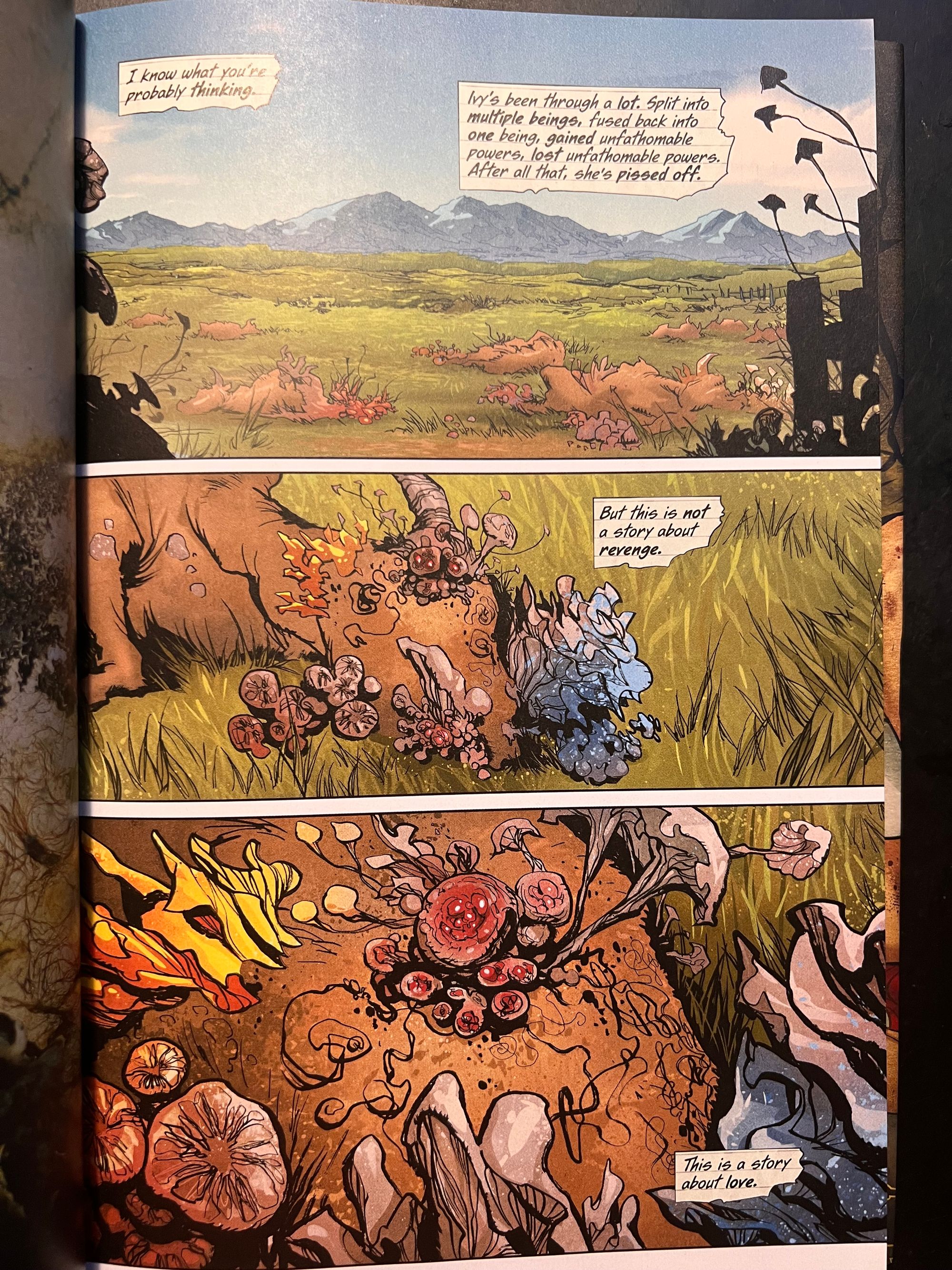

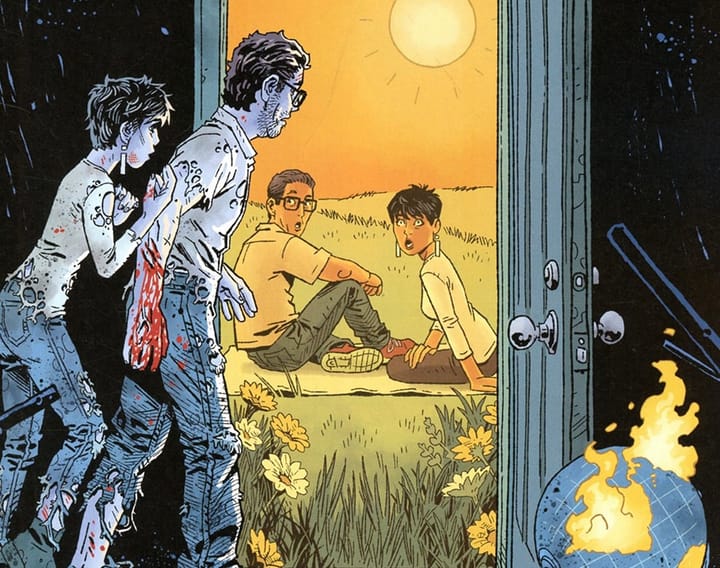

This book feels deeply rooted (pun fully intended) in Alan Moore, Steve Bissette, John Totleben, and Tatjana Wood’s 1980’s Swamp Thing run. Marcio Takara and Arif Prianto’s art and colors (joined for part of the book by Brian Level on art) capture the beauty of nature and the horror of flora unleashed. Takara’s storytelling shows us everything we need to know about Isley; her power, her rage, her control, and her love. Similar to how Bissette and Totleben were able to draw a horror story about nature, Takara’s depiction of that nature weaponized against humanity turns Isley from the victim of some other story into a woman taking control of her life in the most brutal ways possible. It’s about finding the horror in the natural. Takara shows us all of these different sides of Isley, drawing us into her strength and her insecurities, as she navigates her ability to wreak terror in the name of justice.

Wilson gives us a view into Isley’s emotional state through first-person narration in the form of a letter written to her love Harley Quinn. As Isley defiantly road trips across America, her letters to Harley show a woman defined equally by her anger and her love. Wilson’s Isley is more than the supervillain that she’s often depicted as in Batman comics and separating her from Harley puts her on unsteady ground. Usually, she’s either the one in control or the stabilizing influence in an otherwise unsteady relationship. But here, Wilson writes her as a woman trying to fulfill a purpose while trying to fill a void in her soul. She’s lost something and this trip is her attempt to regain it. It’s more than just her powers that are lost; it’s her direction.

With that letter, Isley is writing to us; we’re the recipient of Isley’s internal dialogue. During the chilling climax, she writes to Harley, “I’m telling you this because I know you won’t judge me for it. Well, maybe you will but you won’t hate me for it. And that’s the important thing.” It’s what one lover writes to another, looking to hold onto that connection even as Isley thinks that she’s doing everything she can to break it. And yet it’s also Wilson, through Isley, writing to us hoping that we see Isley for who she is; she may be a monster because of her murderous actions but she’s more than that. Can we read about this troubled woman and not hate her? Isley is asking us for an absolution that an absent lover is not able to provide in the moment.

Poison Ivy: The Virtuous Cycle shows us a woman that’s trying to find herself while she’s also acting on her anger and her sense of justice. Wilson and Takara are showing us that it’s possible to empathize with someone who is multifaceted in contradictory ways; you can view Isley as a villain but still understand where she’s coming from and maybe even sympathize with her motivations. That’s what it is to be human- never just being one thing. This is a comic about a villain doing villainous things but Isley is the hero of her own story and that’s the strong draw into this story. But it’s also a fascinating question that this story leaves hanging— can you be a hero even if your actions are anything but heroic?

Comments ()