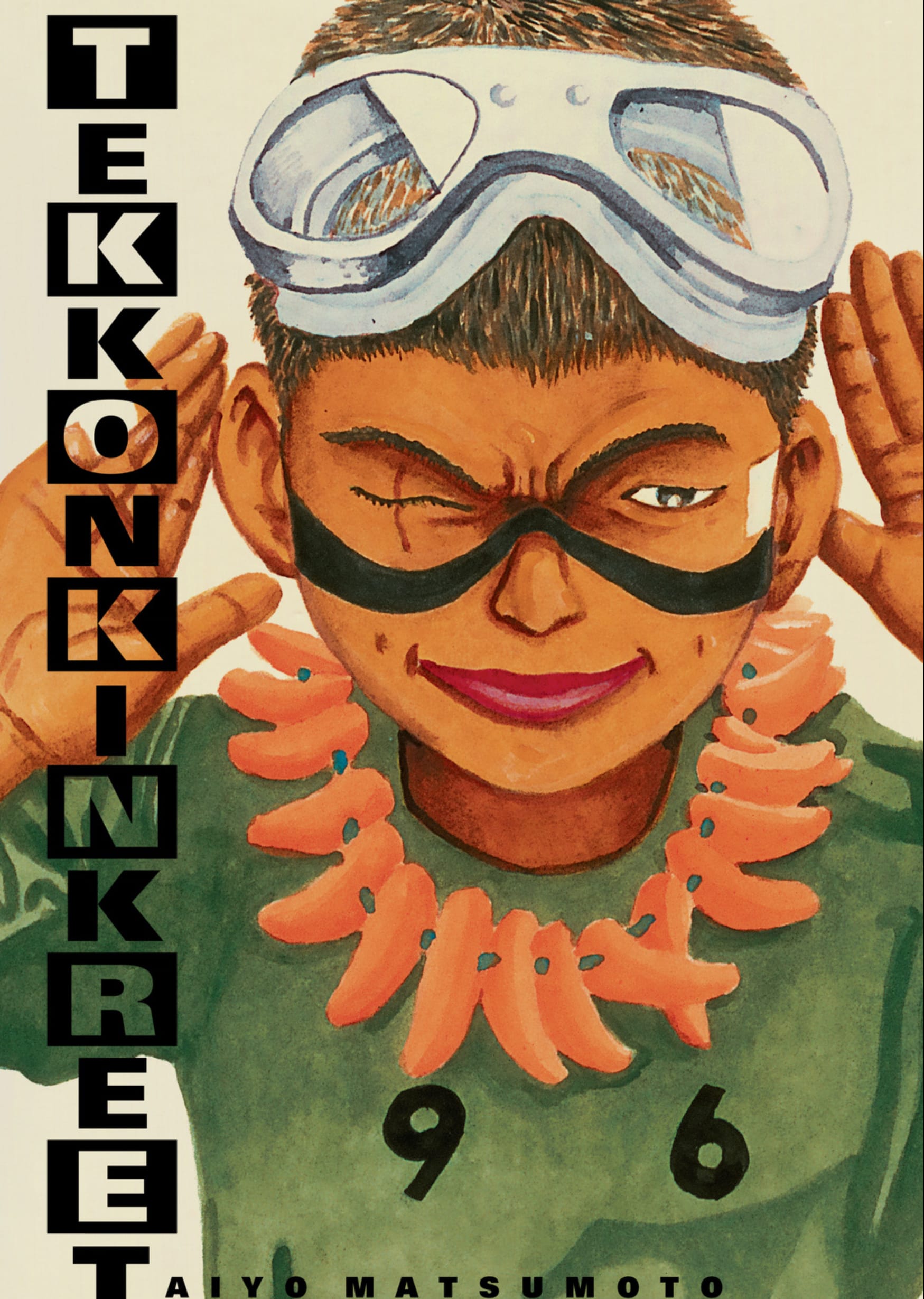

Tekkonkinkreet by Taiyo Matsumoto

Tekkonkinkreet, now 30 years old, is this story of aging, growing old, and trying to preserve the innocence of youth.

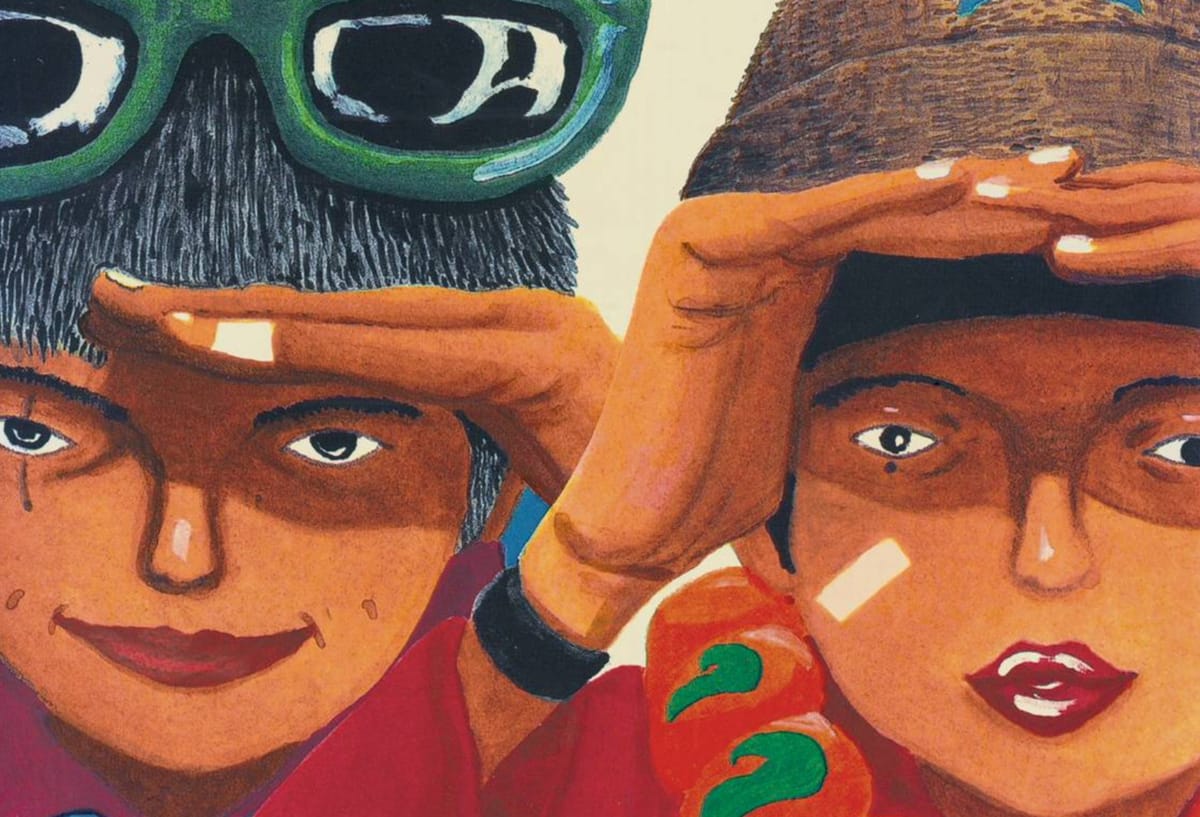

Taiyo Matsumoto’s Tekkonkinkreet lives by its own rules. Two young boys, Black and White, live on their own in an old city, fighting for the spirit of the city that they love but struggling against all of these forces that want to change it into something unrecognizable and without its own agency. Matsumoto, just 26 years old when this originally came out in 1993, is almost trying to create his own Akira, following Katsuhiro Otomo’s lead in exploring what it means to be young in a world designed to chew up its children. Like Otomo’s school-age biker gang, Matsumoto dials into the rebellious outlaw nature that is being a kid, believing you own the world even while the powers that be barely recognize that you exist. It’s the question of how you learn to understand an indifferent world and then grow to change it that Matsumoto tries to answer as Black and White fight their way through an uncaring city and its cruel power brokers.

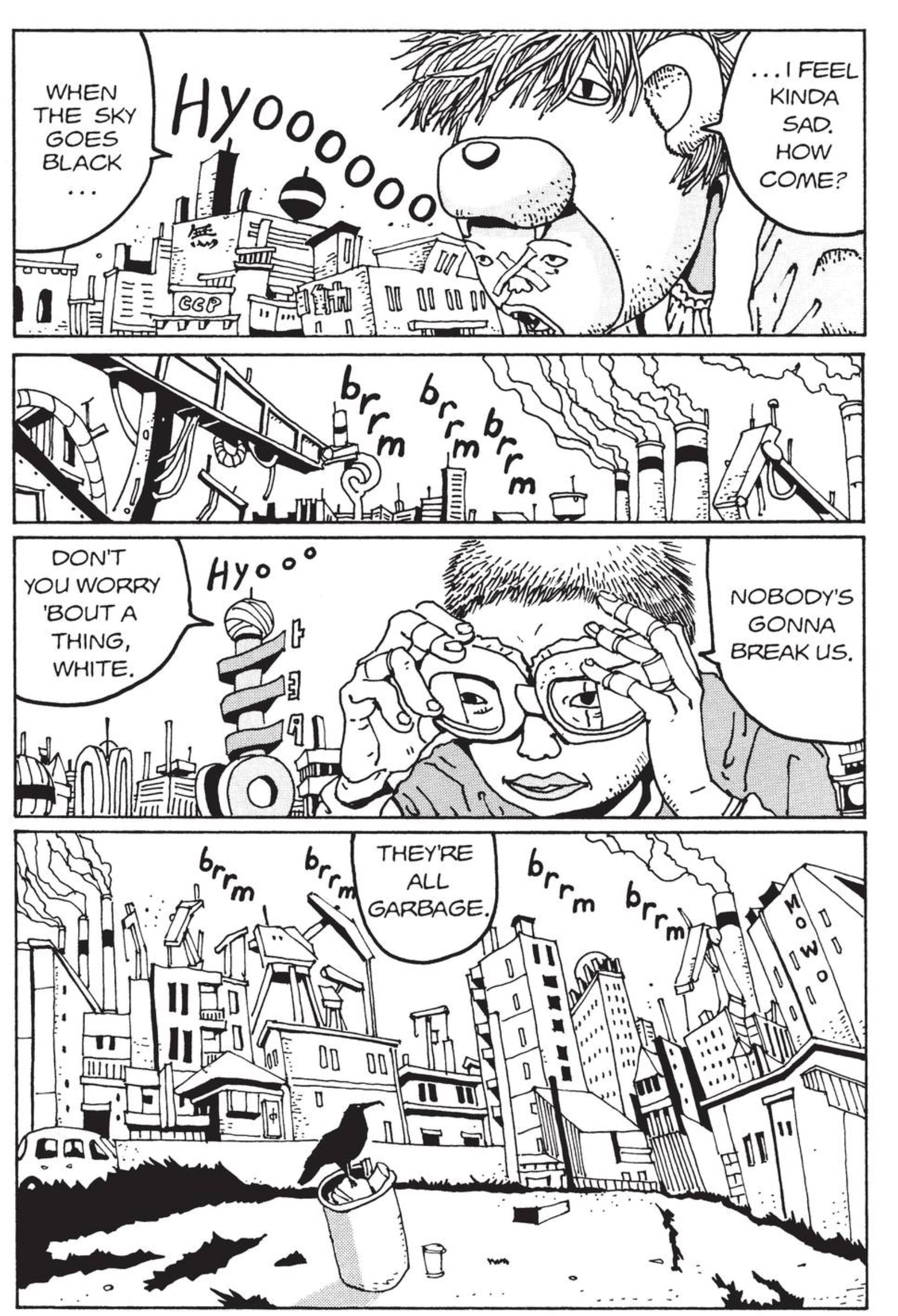

Tekkonkinkreet, now 30 years old, is this story of aging, growing old, and trying to preserve the innocence of youth. Matsumoto’s Black and White are threatened to be corrupted just as their city, Treasure Town, has already been infected by crass wants and needs. Black and White, two young boys on their own in an old city, only have each other for companionship and protection. They run the city, or at least they think they do. From their perch high on buildings and telephone poles, these 10-year-olds watch over the city, looking for the criminals and gangsters who want to burn the city down to remake it in their image. The boys think of themselves as guardians but Taiyo Matsumoto has a much more compassionate view of his characters; he wants these kids to be kids and not vigilantes.

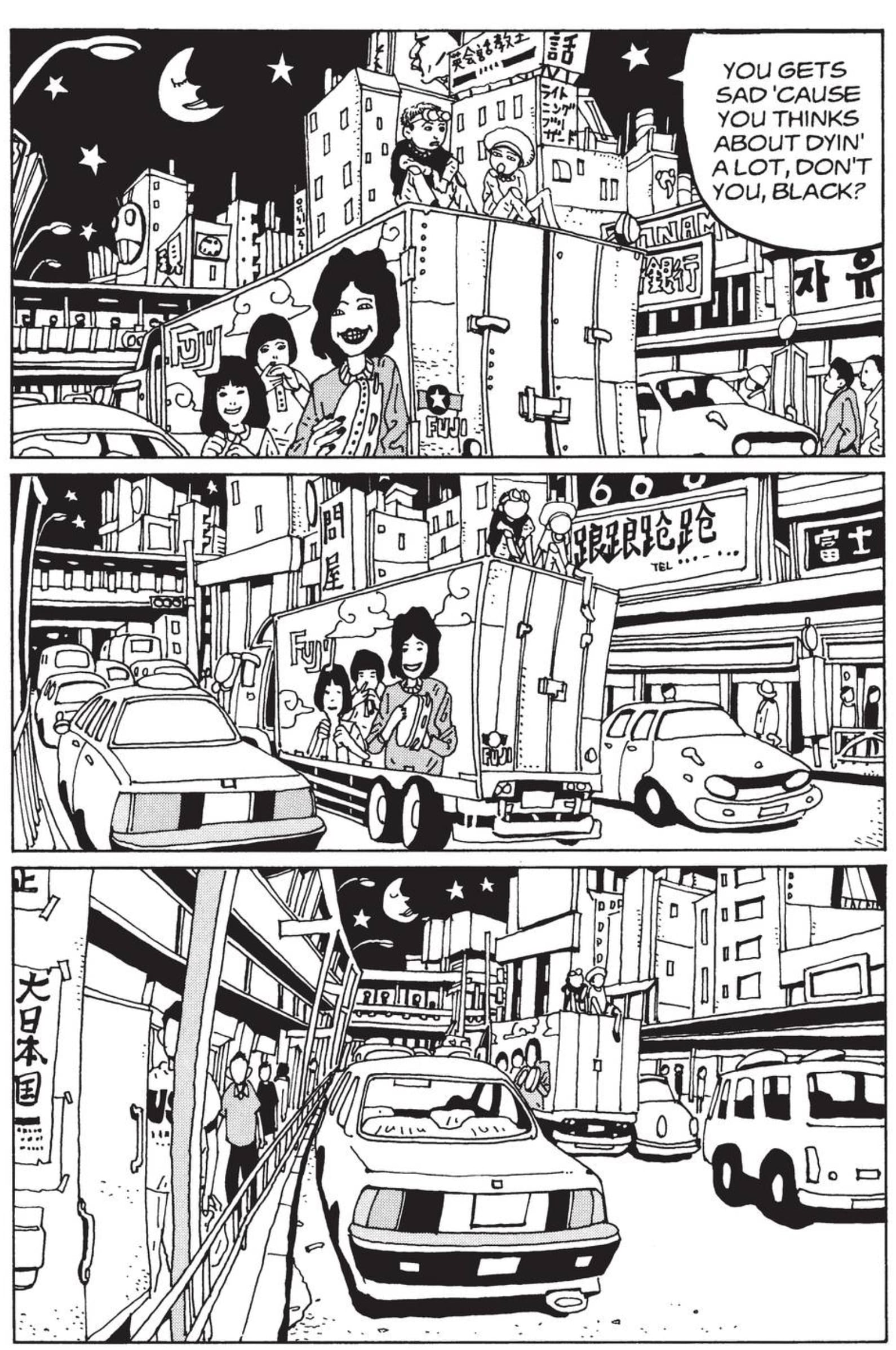

From the start of the book, Black and White have their freedom; they are free spirits in a city that is changing into something different right before their very eyes. The criminals want to gentrify Treasure Town, turning it into Disneyland, their profitable playground. Think of the transformation of NYC from the seedy Times Square of decades past to the tourist attraction that it is now; that’s the future for Treasure Town and the future for the criminals to just get richer and richer. The problem is that it is not the Treasure Town that Black and White love or what the streets of this city even want to be. And the criminals can’t even agree on what the future should be; it’s the new up-and-comers who have the desire to change the city. The old guard criminal, the true Treasure Town hoodlum will go along with their bosses’ wishes even if they don’t quite believe in it themselves. On the other side of the law, you have the cops who are just trying to preserve order. The cops are just there, stuck in this cycle of just trying to maintain some kind of control in the streets.

This is the world these two kids are caught up in, trapped between the gangsters and the cops, and caught up in these battles for control as they just treat the city as their giant playground. Black and White are the chaos agents in this book, the wildcards who keep everyone on their feet but they are also the characters most in need of protection. From the beginning, there is something different about White; he’s slightly out of tune with the world around him so Black is his guardian. Black looks out for White even as White anchors Black in this world. While at first, it seems like White needs Black, Matsumoto shapes the story so that these kids equally need each other in different ways.

Drawing this story, Matsumoto fills every panel and space with so many details, whether it’s just a closeup of a scarred face or a wide shot of the city with the fantastical monuments and buildings that inhabit it. This comic is full of life; Matsumoto’s artwork moves and vibrates in ways that so few cartoonists can bring to their work. Black and White dance through this city, injecting it with youthful naivete that’s exhilarating and even a bit frightening. There are these fantastically designed characters that show up to challenge Black and White, sometimes looking like they stepped out of a different book but still fitting in with the catch-all aesthetic of Tekkonkinkreet. The buildings lean ever so slightly to the left or the right, defying gravity as they work subconsciously to make everything feel just slightly more dangerous like everything is going to collapse into itself any minute now. Matsumoto shows that this is a world that lives on the edge without ever even needing to come out and say it. It’s all of these visual cues of the city and its people that perfectly set up a feeling of inevitability that Black and White are struggling against.

Black and White represent purity and darkness but nothing is ever that clear cut; Matsumoto is operating in shades of gray with them. Sometimes the book leads more towards the light but other times, it gets quite dark, particularly when the two boys are separated from each other by the cops. Without the other to balance them out, their worlds and equilibriums are all thrown off. These two boys are individuals but there are also ways that they are a single whole, stronger together than apart. Together, they take on the world, fighting anyone who comes along challenging them. They’re scrappers but they’re also ferocious and that’s something that they’ve learned from this city.

But apart, each boy is lost in the world, unable to operate. This system that Black and White form is a protection of the innocence that each possesses but has been buried deep down. Matsumoto expresses a deep desire to hold onto childhood through these boys, to hold on to that innocence that we lose as we grow up. Maybe even more than a struggle of good versus evil, Tekkonkinkreet looks at the fight between staying young and growing old. There are all of these adults around Black and White who feel like they’ve succumbed to the city for better and for worse. The criminals and the cops have made compromises as part of growing old and that’s something that the two youths just can’t do. Like their names, they have a very black-and-white view of the world that youth allows kids to have that we lose as we grow up to time and age just wearing us down.

Comments ()