The Breaking of a Good Man— a look at Garth Ennis and Goran Parlov’s The Punisher: Valley Forge, Valley Forge

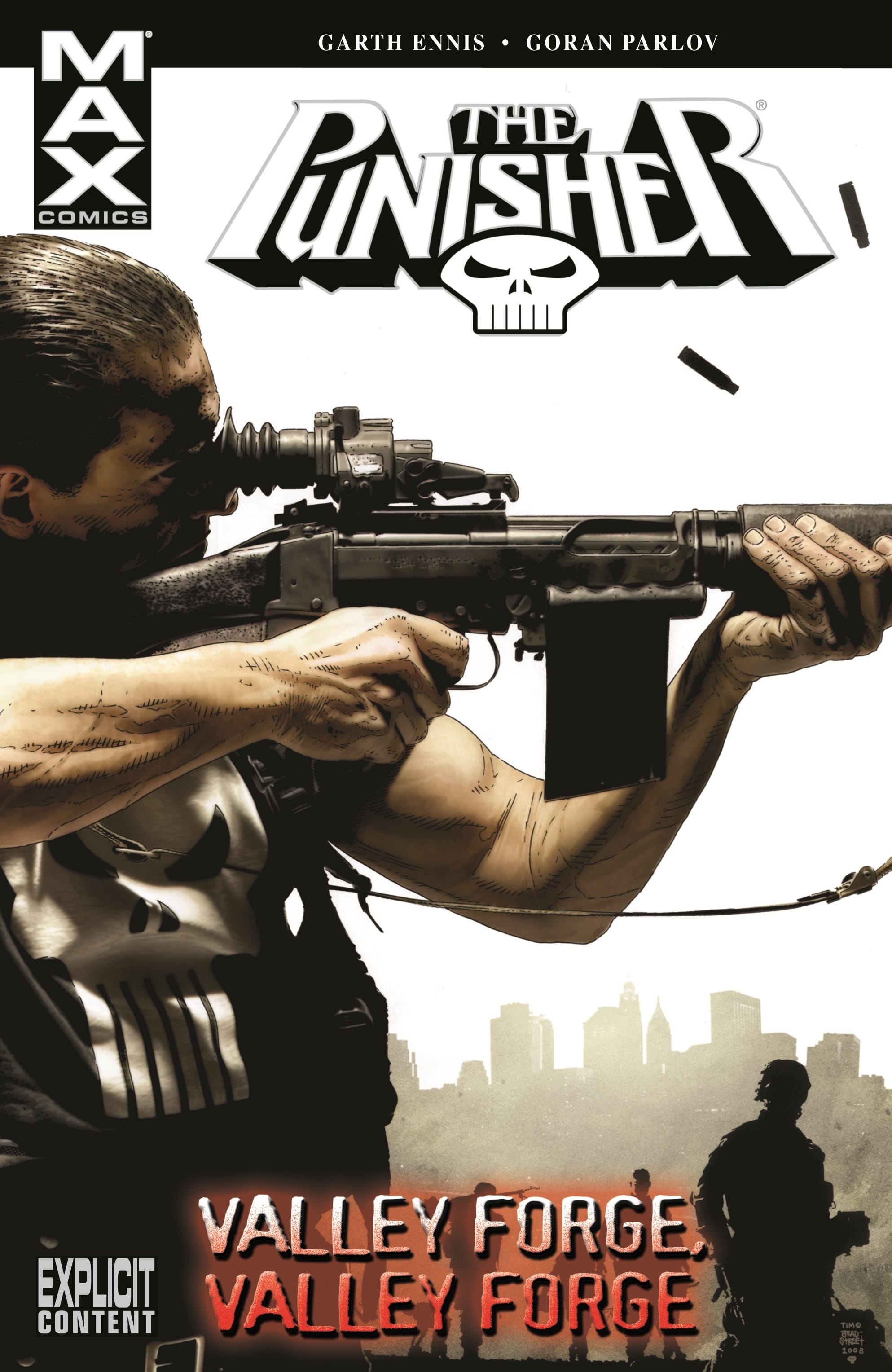

Maybe it’s not the right time to be writing about a lone gunman prowling the streets of NYC. Or maybe it is as Garth Ennis and Goran Parlov are less focused on the exploits of Frank Castle the man and more dialed into the symbol that is The Punisher. The Punisher: Valley Forge, Valley Forge (2008) isn’t the story to go to if you want to know what makes Frank Castle who he is: there are plenty of other comics (most of them written by Ennis) or that. Valley Forge, Valley Forge isn’t a story about Frank Castle and his adventures. It’s something deeper and more meaningful than that. Ennis and Parlov, an Irishman and a Croatian, instead are digging into power in this book, particularly American power and the people who wield it. And ultimately, it comes down to this isn’t a war story or a superhero story or even a vigilante story— it’s a story about business.

Threatened by secrets that Frank Castle could expose, a group of military generals tasked the one good man, Colonel George Howe, and his special forces on a mission to bring down Frank Castle once and for all. Howe is a good soldier who sees Castle as the army’s responsibility to bring to justice but the general’s vision for this mission is that Howe’s soldiers will kill Castle and take their secrets with him. Interspersed throughout the story of the hunt for Castle are excerpts from a book about Firebase Valley Forge, an American camp that was slaughtered during the Vietnam War; the only survivor of that attack was Frank Castle. Ennis had previously told this story in the book The Punisher: Born (2004) but brings it back up in this book to create a dialogue between the war that created The Punisher and the war that Frank Castle is still fighting decades later.

Parlov and colorist Lee Loughridge’s work in this book is very understated. So much of the story is dialogue-driven, which has always been a joy when it comes to reading Ennis’ writing. So that leaves Parlov to draw men moving through the shadows, hunting the ultimate prey, and going through their own moral battles. Well, men other than Frank Castle. Ennis and Parlov know who and what Frank Castle is; that’s been well established in other books so this story is more about what Frank Castle means to so that’s what Parlov is drawing. It’s like he’s drawing a portrait of The Punisher but reflected in the faces of these other soldiers. We see the fear that The Punisher brings out, the anger, the sadness, and the resignation of these characters as they look upon one of their own as their own personal weakness or failures. And we see that in Howe’s sunken eyes, a proud career military man faced with the truth of what is at the heart of the American military.

That’s not to say that when they need to, Parlov and Loughridge can’t turn it on for some juicy action. This isn’t an action story but it does have its moments where Howe’s soldiers think they have Castle cornered and can take him down. These scenes are played just to show how much Castle is in control of everything that is happening. The first confrontation with two of Howe’s men is a cat & mouse game that Parlov and Loughridge just sink into. One portion if it is just a stare down to see who will blink first and you’re just waiting for something to break the tension. Another moment is a showdown in a cemetery where Castle faces down Howe’s whole team. It’s a strong sequence that shows where Castle seems outgunned and outmanned. The art is loose but each line is just the right line for the moment.

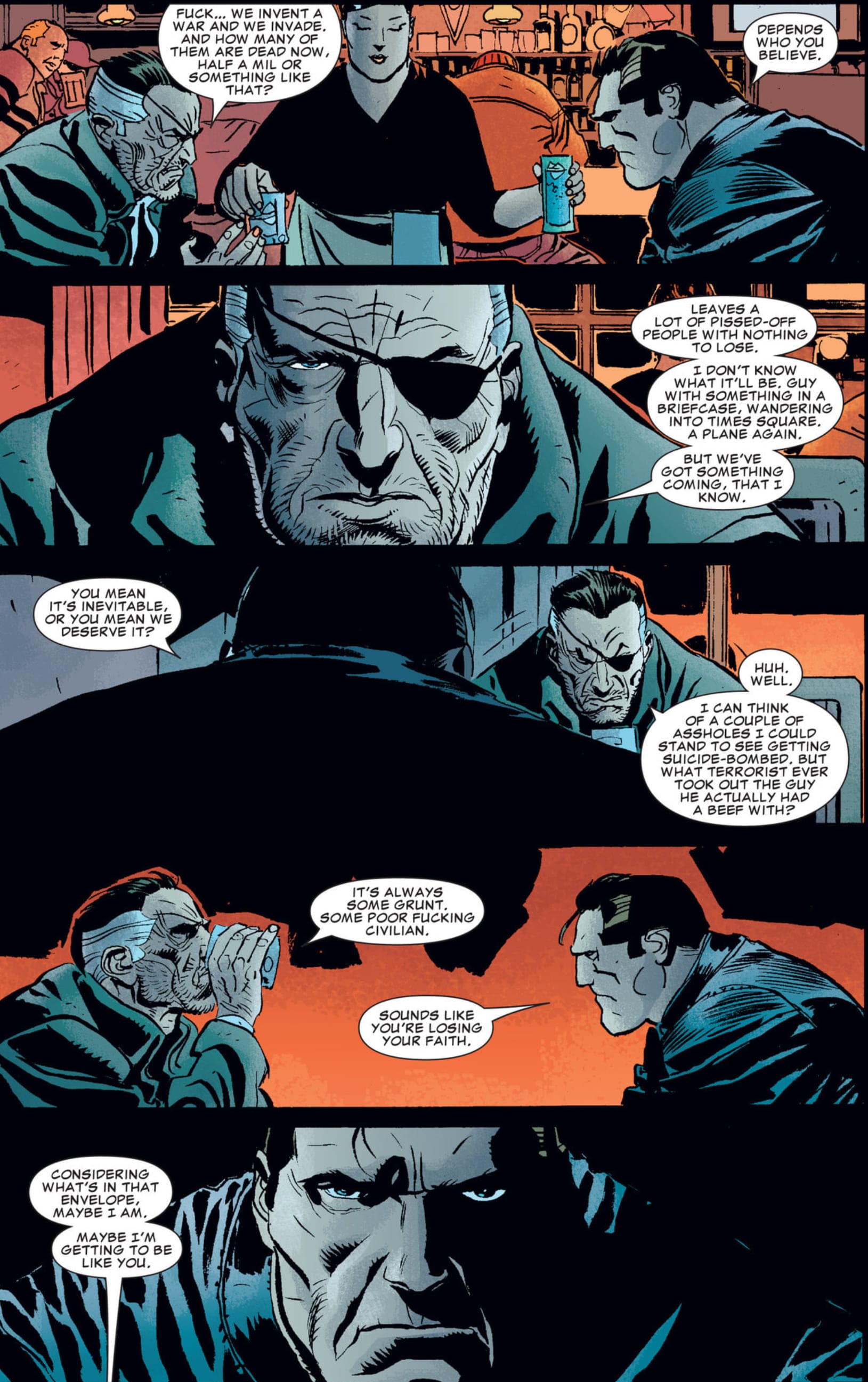

Ennis’ story forces us to ask just who are the good guys. An aged Nick Fury plays a small but pivotal part in this story. At a meeting in a bar, Fury watches television of war in Baghdad and philosophizes on his and Castle’s part in the ongoing wars that America fights and the death of innocents. “Sounds like you’re losing faith,” Castle says. “… Maybe I’m getting to be like you,” Fury answers back. It’s that cynicism of the good men, like Fury and Howe, that drive this story— the idea that there’s maybe something righteous that these men are doing even as they know that their actions are anything but righteous.

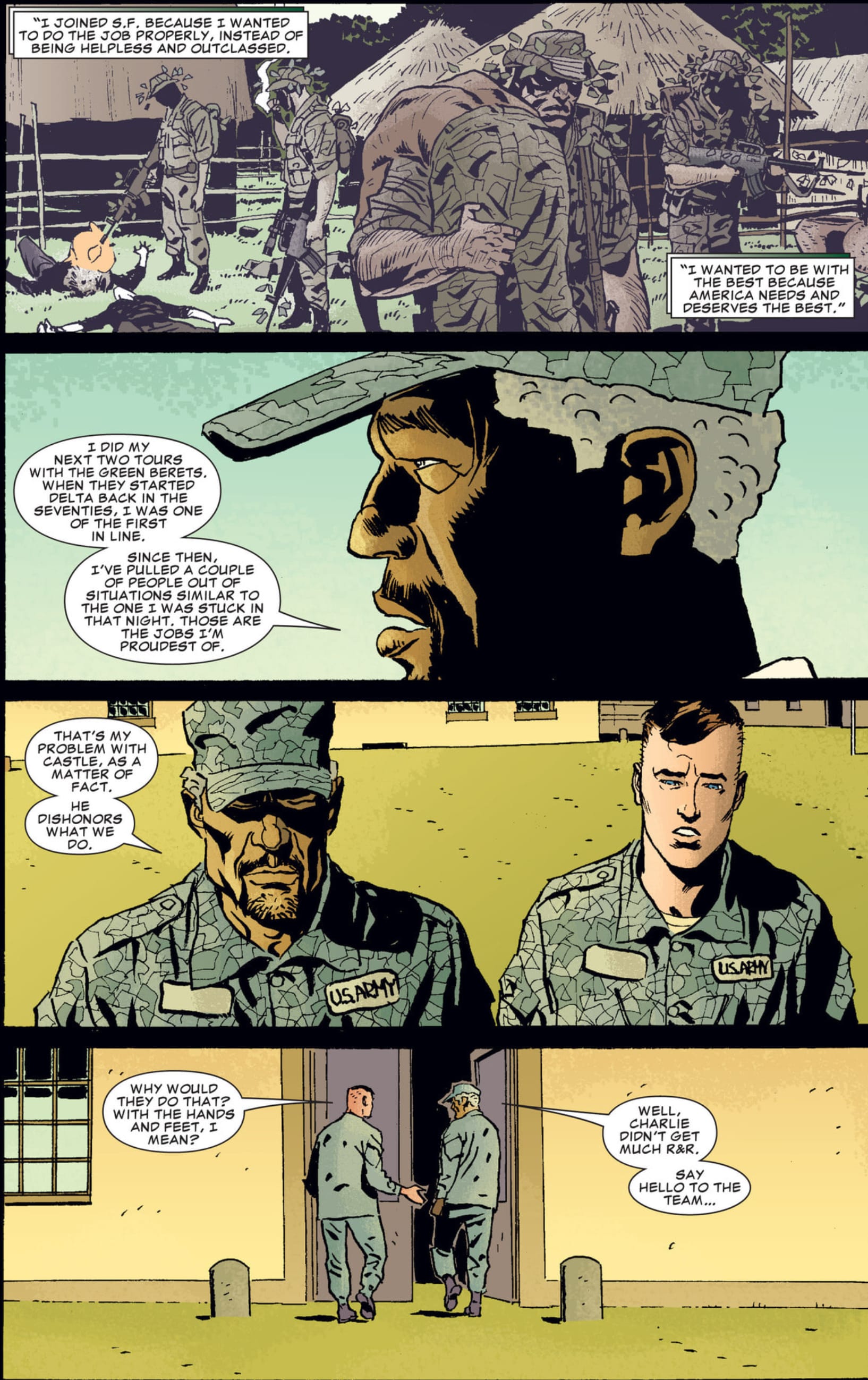

Howe genuinely is a good man. He’s a career soldier not because he’ll get something out of it. He’s a soldier because he believes in what he’s fighting for. Even his acceptance of the mission to hunt down Castle is tied to that righteousness. The men giving him the orders are just trying to save their own lives but Howe believes he can do some good by pulling Frank Castle out of his own war. That goodness even carries over to Howe’s men. They’re soldiers following orders from a man that they believe in. Ennis never comes right out and says this but his writing and the ways that Parlov draws them express that these are good men who are doing this because they believe in the necessity of the mission.

But someone in this story needs to face up to reality. And it’s not the generals, it’s not Castle, and it’s not Howe’s men. There’s a good man at the center of this story who has to face the ugliness of the world that he’s operating in. Even if the spirt of the orders that Howe is given is small and petty (basically, it’s self-preservation by some scared men,) Howe accepts it because he believes that he can save Castle. As the story progresses, we discover that Howe has his reasons for believing in Castle more than his commanders but he eventually ends up caught between the generals and Castle. He himself is ultimately powerless against either, a hard truth that he needs to face. Much like Fury in that bar, Howe has to wrestle with the idea that maybe he’s a bit more like Castle than he thought.

After an almost 8 year run on The Punisher that began in 2000, 2008’s The Punisher: Valley Forge, Valley Forge wraps up Garth Ennis’ time chronicling the life and times of Frank Castle. And instead of going out with guns blazing, Ennis and Parlov tell a meditative story, an earnest and moral story about the injustices of American war and the American military industrial complex. And just like Howe and Fury, Ennis and Parlov are challenging us to reflect on our own roles in these wars. We may not be soldiers or generals, but these wars are supposedly there to protect us and our interests. But it’s fairly obvious that Ennis doesn’t think our self interests are in anything more than protecting our wealth.

Comments ()