My Claremont Year- March/April 2023

This period around 1982/1983 marked a shift in the X-Men characters themselves, turning them from superheroes into characters who are often wrestling with themselves as much as they are the bad guys.

Around the end of 2022 a thought struck me; have I ever read all of Chris Claremont’s X-Men? I think I’ve collected it all in one form or another (or even multiple forms) but there’s a point in the mid-1980s where a lot of it becomes fuzzy in my memory. I probably read it when it was coming out but more out of the inertia of collecting than any love of it. So armed with several omnibuses, Marvel Unlimited, and whatever back issue diving I need to do, I’ve set the goal to read his 16-year run on X-Men, New Mutants, and other related books, probably also eventually including some Louise Simonson New Mutants and X-Factor here as well since the series are so tied together.

As much as this is to check out these stories again, I want to see if there’s a completeness to the story that Claremont was telling, starting with his first issue, X-Men #94 (1975), and extending all the way through X-Men #3 (1991). Maybe by the end of 2023, I’ll have some kind of grand unified theory of Chris Claremont’s time on the book or maybe I’ll just have read a lot of comics that range from “not bad” to “what were they thinking?”.

This month, we're covering 1983 to 1984, the heyday of Claremont's run on Uncanny X-Men.

- Uncanny X-Men #167- 188

- New Mutants #1- 21

- New Mutants: Renewal Graphic Novel

- X-Men: God Loves/Man Kills GN

- Uncanny X-Men Annual #6 & 7

- New Mutants Annual #1

- Special Edition X-Men #1

- Marvel Team-Up Annual 6

- Wolverine #1-4

- Magik #1-4

- X-Men and The Micronauts #1-4

So this is where things really start to get interesting.

So this is where things get interesting as Marvel clearly realizes the hit they have with Chris Claremont’s X-Men. While Uncanny X-Men had been allowed to just exist really by itself from 1975 through to 1981, 1982 is when things start expanding just a bit, first with two graphic novels (one of which introduces a whole new team of mutants,) and the first Wolverine miniseries, with art by Marvel superstar Frank Miller. And then with the launch of the ongoing New Mutants series, the X-Men became a franchise. And perhaps with the popularity of the book he was writing came an amount of freedom for Claremont to turn the X-Men into outlaws even as they fought for the good of mutantkind and mankind.

Going back to Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, the idea that the X-Men were feared and hated for being mutants is central to the myth of the X-Men. It’s the “we fear what we don’t understand” mentality that’s defined who the X-Men are. Spider-Man is just hated because he’s Spider-Man but no one thinks about his origins as the source of his powers; the origin isn’t the cause of Spider-Man’s lack of respect. But as soon as someone in the Marvel Universe is labeled “mutant,” that’s it; that’s enough to hate them. Maybe it’s the thought that characters like Spider-Man or the Fantastic Four are still essentially “human” while mutants are something else. To go back to the idea of mutants being stand-ins for various persecuted and discriminated-against people, there has always been an othering of mutants. They’re not us and that’s enough of a reason to hate them.

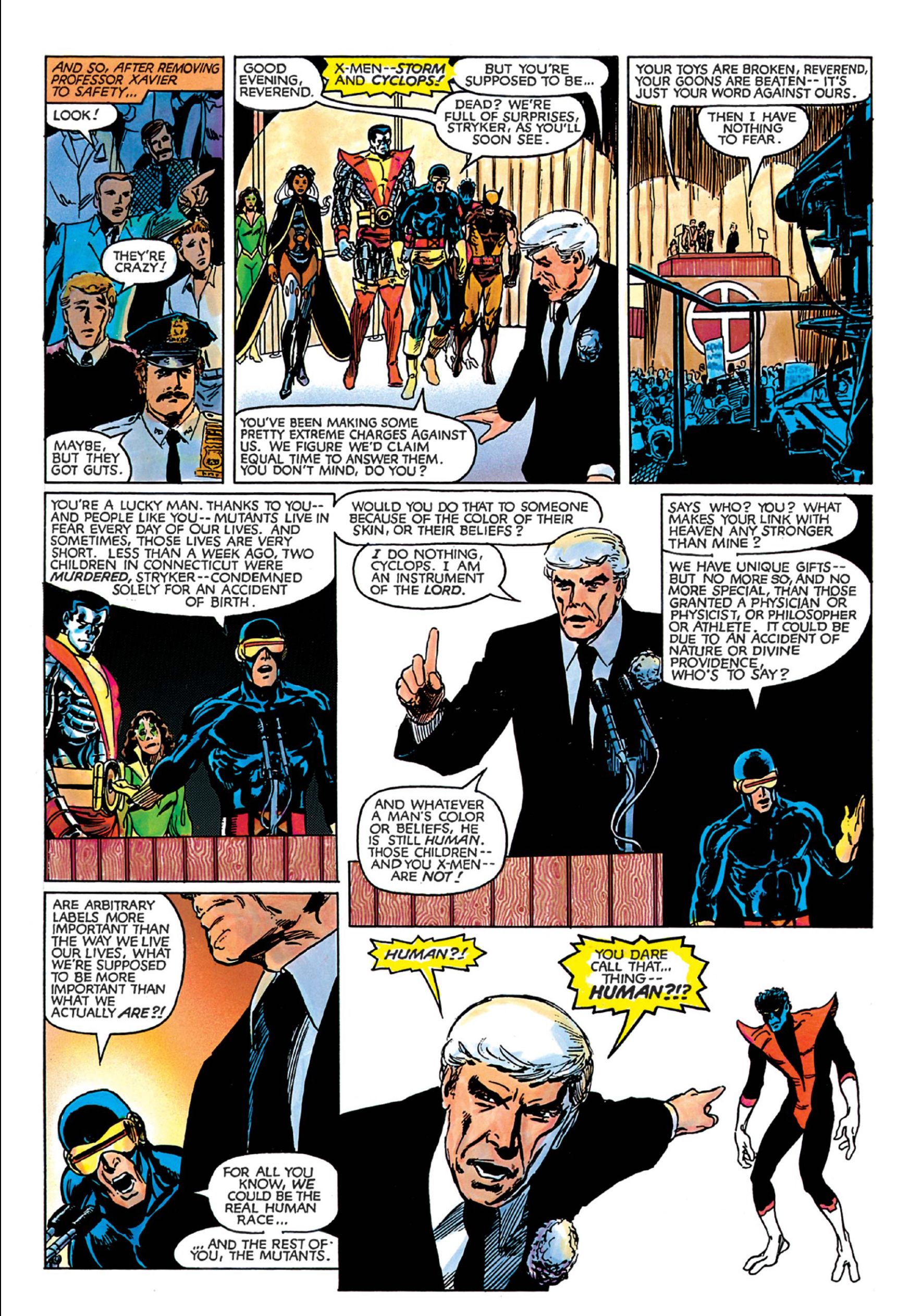

Around “Days of Future Past,” Claremont started to explore that more, suggesting that we would have concentration camps for mutants in the not-too-distant future. For some reason, back in 1980, that seemed very pessimistic but as we look at the past 100 years of history, particularly of the United States, it honestly doesn’t seem that unrealistic to imagine, especially if mutants would ever have been viewed as threats to “the American dream.” So by 1982, with the “God Loves/Man Kills” graphic novel, Claremont goes all the way and has the X-Men as the target of religious extremists, proposing the annihilation of mutants as a race all in the name of genetic purity. It’s still quite shocking how the Brent Anderson-drawn graphic novel draws lines from mutants to Jews and Black people and the inhuman persecutions that comprise the histories of those two peoples.

Claremont went there. In that graphic novel, Claremont draws straight lines from Jews and Black people to the mutants, The young ingenue Kitty Pride was depicted as Jewish right from the beginning and the book opens with her wearing her Star of David necklace as she pummels some prejudiced little Westchester, NY punk. And in her anger, she asks her Black dance instructor “Supposed he’d called me a N——- -lover, Stevie?!” Only Claremont used the word and Marvel printed it. But right there within Kitty’s anger is the convergence of all of this hatred and bigoted persecution. Claremont and Anderson’s work on this story signifies a shift in Claremont’s writing from being a superhero soap opera to being a series where Claremont can start exploring what it means to be “feared and hated.”

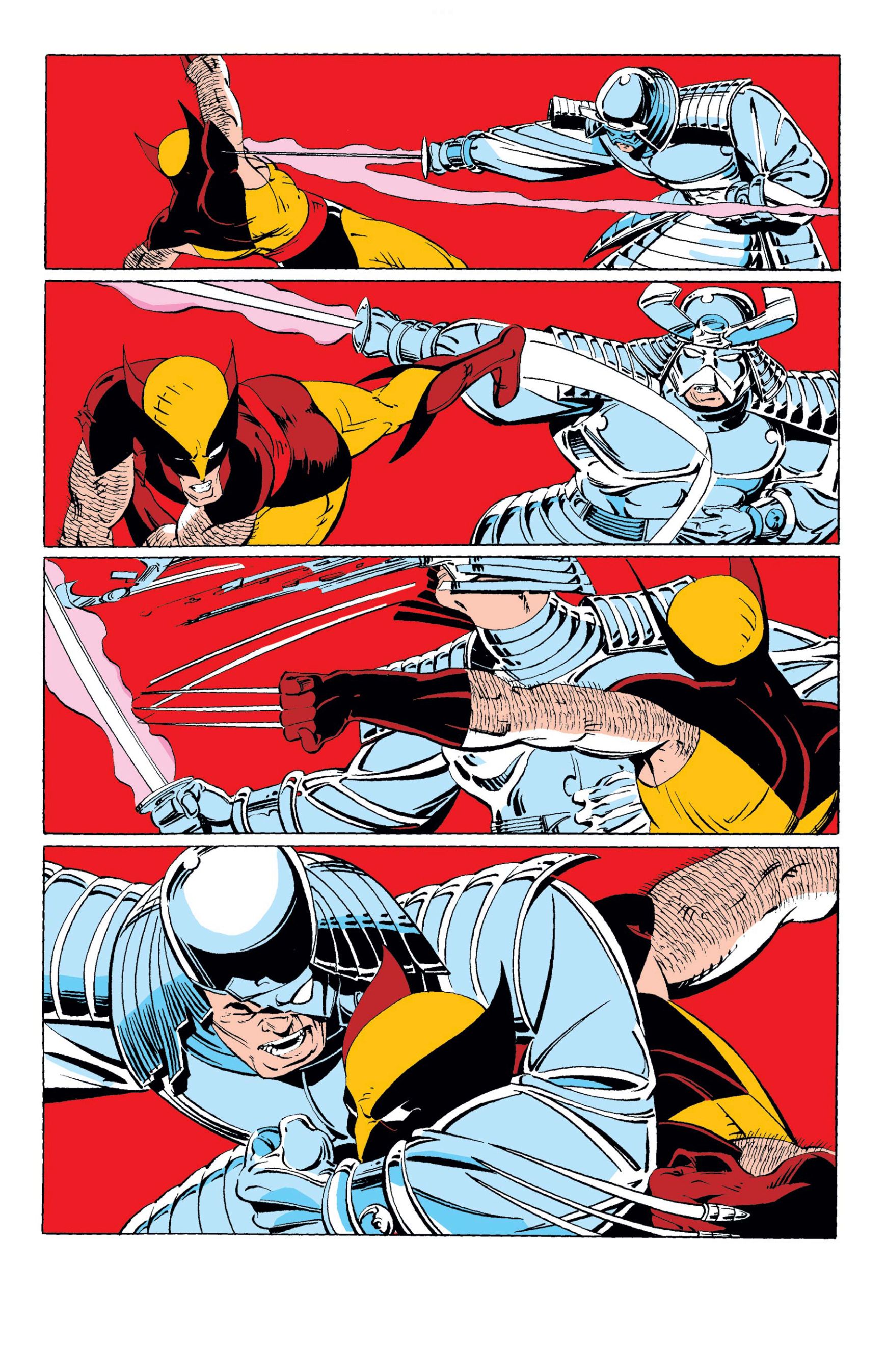

This period around 1982/1983 also represents a shift in the characters themselves as Claremont begins to see them as more than novice superheroes as so much of his previous writing has. The miniseries Wolverine introduces the iconic line “I’m the best there is at what I do, but what I do best isn’t very nice,” in the first issue. It almost perfectly defines Wolverine so much that it’s become a joke how often that line has been repeated over the years. Claremont had always hinted at this side of Wolverine but never really showed it in the team environment, except for Wolverine’s attack on the Hellfire Club during “The Dark Phoenix Saga.” In the miniseries, Claremont finds the opportunity to dig into Wolverine and bring out all of these traits and skills that he had only been able to previously hint at.

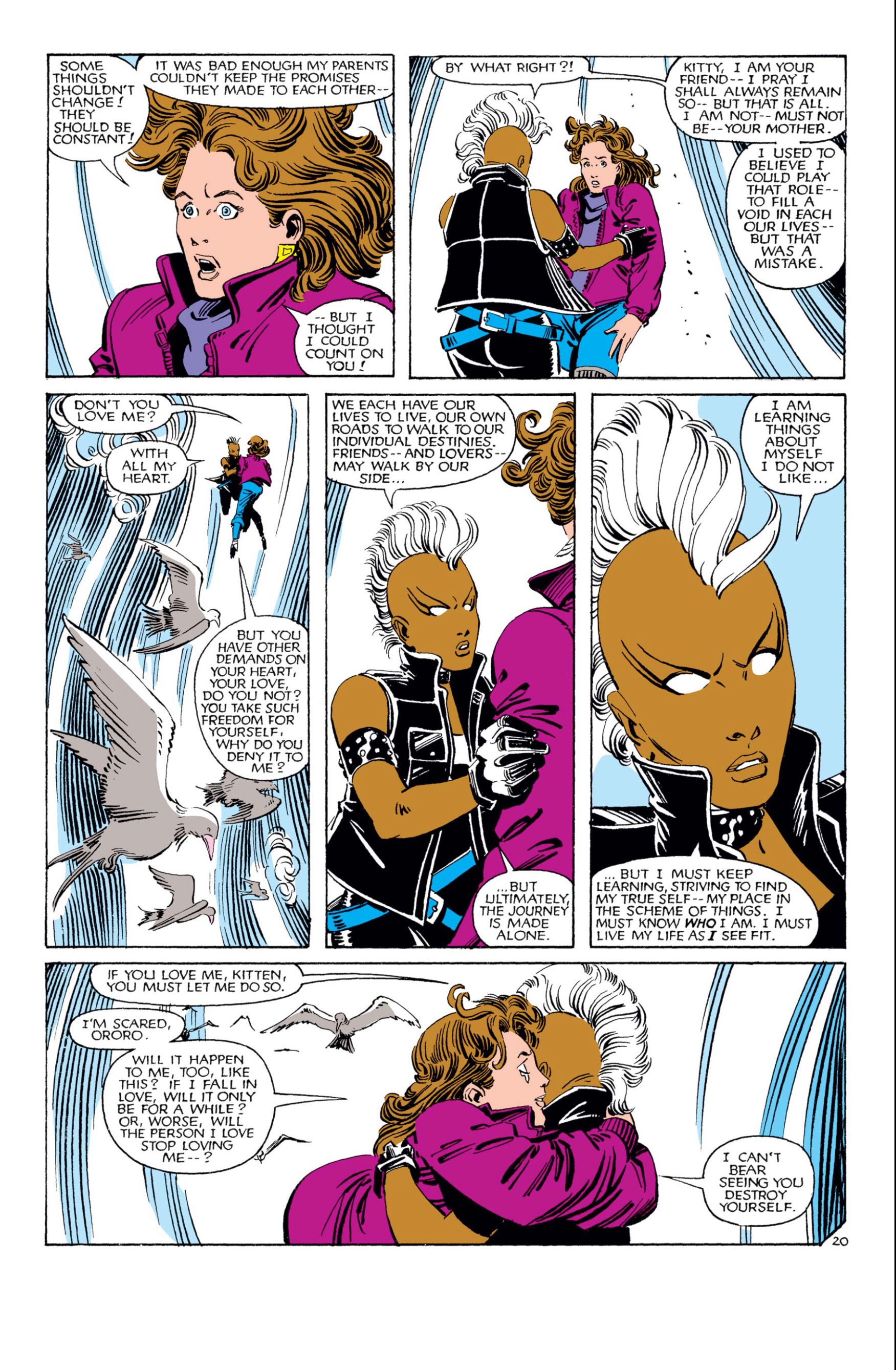

The miniseries doesn’t so much redefine Wolverine as it does build on everything that had been done with the character before and it’s interesting to watch Claremont revisit Wolverine and other characters like Rogue, Illyana Rasputin, and Storm (more on Storm next month) throughout these couple of years. A villain, a child, and a goddess get the same treatment during these years as the brawler. With the two main Uncanny X-Men artists during this time, Paul Smith and John Romita Jr., Claremont has two character-driven artists that harken back to the work of John Byrne. Romita Jr., very much his father’s son, is a strong paring to work with the Claremont soap opera, really able to build character even as punches are being thrown. He can do both the loud and the quiet moments of these stories.

And then there’s the introduction of The New Mutants, returning to the idea of the X-Men as students learning to use their power. Claremont, Bob McLeod, and Sal Buscema establish this new group, often playing their youth and inexperience against the more mature and experienced X-Men. It’s like Claremont loves the idea of Xavier’s as a school and realized that the X-Men have grown beyond that but still wanted to play in that world. This cast fills in that role but Claremont struggles a bit with landing on what this team is– are they a new team or just X-Men wannabes? And what kind of adventures should they have? He shuffles characters in and out, quickly dropping Xian McCoy, a character he created even before The New Mutants only to introduce Roman-by-way-of-Brazil Magma in an overly long story that sends this young team to the Amazon.

McLeod and Buscema are solid artists in the modern Marvel way so it’s quite a shock when Bill Sienkiewicz takes over in The New Mutants #18. He had done a few issues of Uncanny X-Men before this, where more of his Neal Adam’s influence showed through. But with “The Demon Bear Saga” (everything’s a saga here,) the title turns into a dark horror, where the threat is far more psychological than physical, even as one of the team lies nearly dead after a horrific attack by the spirit bear. Claremont and Sienkiewicz hit on something as the series finds an identity of its own, visually. With John Romita Jr. on one book and Bill Sienkiewicz on the other, Claremont finds this period where he has two books that are connected but have distinct flavors thanks to the artists.

So this period is marked by expansion as it starts piling up miniseries and spin-off titles but also as Claremont begins to let the characters push the boundaries of what their role in these teams is. And he must have been onto something because you can see a lot of what he’s doing with Wolverine and Storm and Kitty be what defines them for decades afterward. There are ways that these characters are trapped in the amber of this period. The settings and conflicts may change but the characters today are still largely the characters as Claremont wrote and defined them. In these issues, we see him not comfortable with maintaining a status quo but yet so many writers and artists after him have returned to these issues to build on the character (see Storm’s recent image change in X-Men Red that’s meant to recall the punk stage of the character.)

The earlier work of Dave Cockrum and John Byrne built so much of the foundation that Claremont built his vision for these characters on but it’s with Paul Smith, John Romita Jr., Bob McCleod, Bill Sienkiewicz, Frank Miller, and others that Claremont tests the footing of that foundation, seeing how far he can push these characters while remaining true to their inner struggles and emotions.

Comments ()