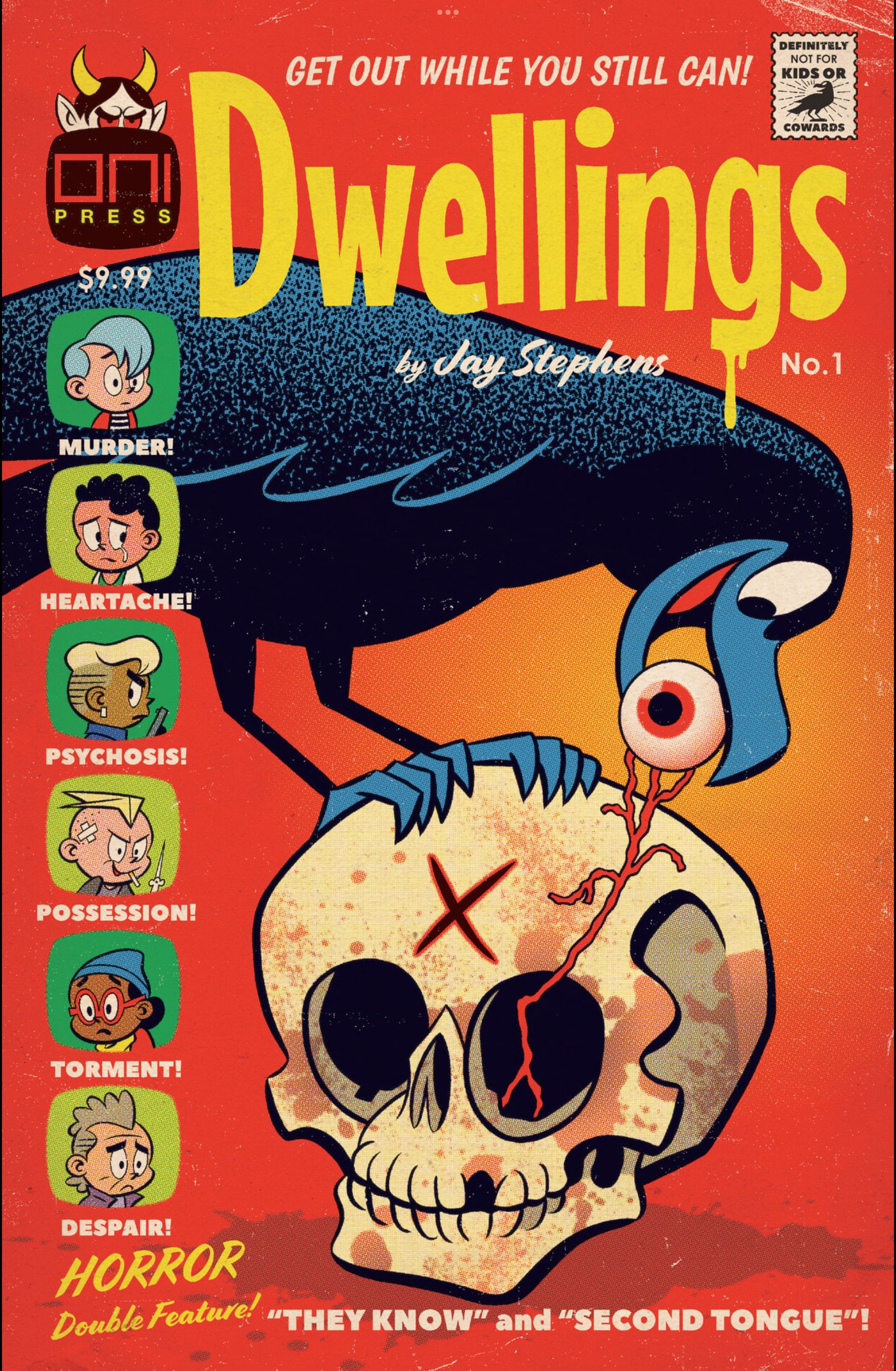

Too Cute to Be Scary or Too Scary to be Cute?— Jay Stephens’ Dwellings #1

Somehow, these stories manage to be disturbingly dark but adorably cute.

Imagine a world where today’s comics weren’t shaped exclusively by the comics of the Marvel and DC books of the 1960s and 1970s. Jack Kirby, Steve Ditko, and Carmine Infantino could still have done the work that they did just without the endless imitators that followed. In this hypothetical world, instead of Marvel and DC dominating the market, we all would have been reading Disney, Harvey, and Archie comics that would have cemented what we thought about comics and cartooning. Comics would continue to evolve into the 1980s, maybe with Frank Miller trying to be Warren Kremer instead of Jack Kirby. Deconstruction of Archie Andrews and Casper the Friendly Ghost could have still come during that time, followed by the Image Revolution but all based around the look and feel of a Richie Rich comic. Got that picture in your head? Good.

Cartoonist Jay Stephens’s new book Dwellings #1 comes from that imagined world. But in this world, the stories in the comics have not remained stagnant kid stuff. Just like in our world, new writers and artists have come along in this dreamt-of world to push comics so we would get crime comics, romance comics, action comics, and yes, even horror comics where the stories have developed to match the growing tastes of their audiences and creators. Back in the 1990s, Jay Stephen’s already had one foot in this world; during the Image Age of comics when everyone tried to look like the bastard child of Rob Liefeld and Jim Lee, Stephens was giving us wonderfully retro books like Tales of Atomic City and The Land of Nod. Before he abandoned us for presumably a better-paying gig, Jay Stephens’s stories harkened back to a different mode of comics than the grim-and-gritty zeitgeist that was the 1990s.

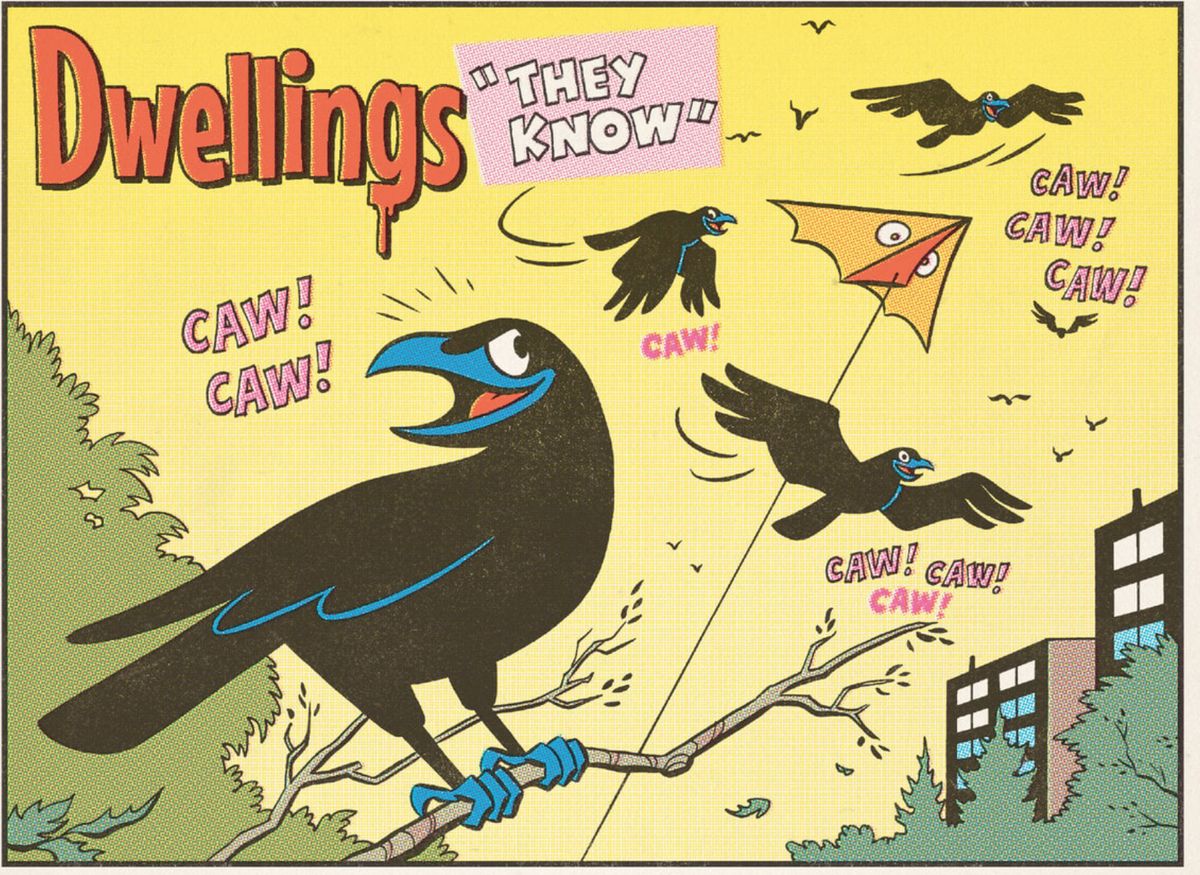

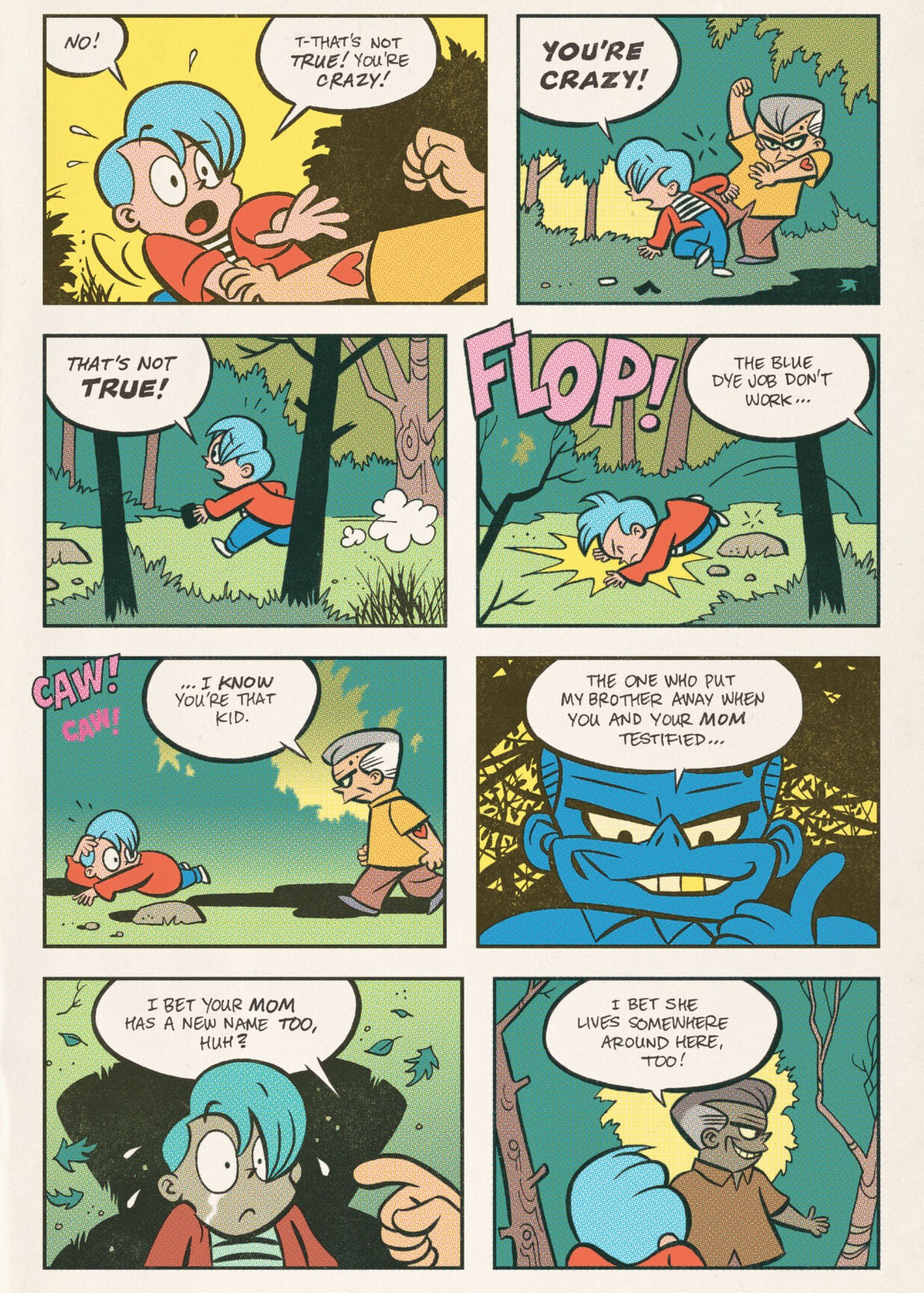

Both stories in this comic take place in the fictional town of Elwich, Ontario, which seems from the outside like a normal, bucolic Canadian town but both stories quickly reveal a darker side to Elwich’s character. The first story features a young man, who after accidentally killing someone, is haunted by crows until in his madness he becomes a killer. In the second story, a psychiatry student visits the town, hoping to gain insight into another dark secret that the town hides from the outside. Like the first story, the student Dawn finds herself caught up in the horrors she’s trying to research. In the two stories, Stephens follows these characters who become trapped by forces that are trying to pull them into the town’s frights.

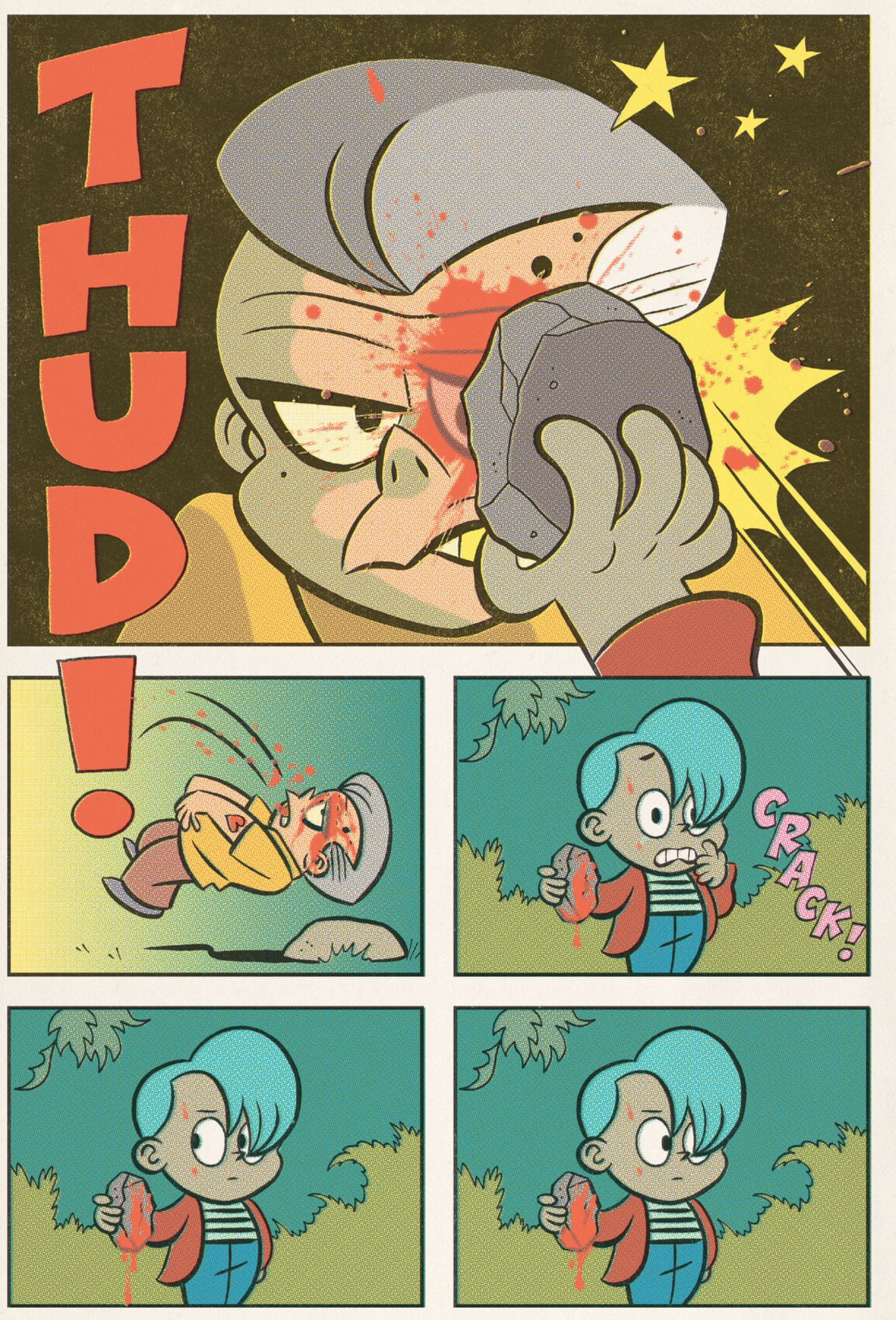

Somehow, these stories manage to be disturbingly dark but adorably cute. Stephens navigates this tension between his images and his plot, drawing these creepy and suspenseful stories in a clear and bouncy style. But it’s almost scarier this way because there are none of the usual ways to hide what’s happening- no shadows or visual misdirections. After all, that’s just not built deeply into the vocabulary of this kind of cartooning. In the first story, after 19-year-old Jordan kills a man in a park, his descent into madness is almost worse because he looks like any other precocious kid. It’s like Richie Rich had a psychotic breakdown and killed everyone in his family; it seems like most versions of that today would be drawn in a more realistic style (see Archie Comics’ recentish attempts at horror) as if bringing the characters more into a world that we would expect those horrors to occur in. Stephens keeps the style and the visual rules of these kids’ comics firmly in place but he unleashes a spiritual darkness on them that seems even more insidious because of our perceived innocence of these child-like characters.

Stephens is operating on what we would think to be two different levels— a visual one that speaks to our childhood and our innocence and a plot level that’s a reminder of just how cruel and broken the world is. As we see take in his approach, Stephens doesn’t act as if there is a disconnect here. Or at least he is using these stories to show that those disconnects aren’t really there. He’s telling these psychologically twisted stories that are frightening no matter what the visuals are. Stephens is diving into these dark stories of these broken and hurting souls that match any horror story on the big screen today. And it’s all there; it’s all right up front on the page because his art doesn’t try to hide from the audience. This kind of cartooning is really all about the character and the emotions of these people. It’s actually kind of refreshing to read these kinds of stories and be able to experience them on this child-like level because that’s what the art allows us to do. Scooby Doo is one of the things that comes the closest to this in terms of mingling stories and genres but Jordan’s madness would permanently scar Shaggy, Thelma, and the rest of the gang.

Comments ()