When Richard Corben met Hellboy

The humanity of Richard Corben’s Hellboy work is that it doesn’t try to spare the reader of anything.

Opening up a Richard Corben Hellboy story is like stepping into another world. There’s our world, Hellboy’s world, and then Richard Corben’s world. It’s a progression away from the safety of reality into the sublime, fantastic, and horrific vision of what the world could be and then into what it probably really is. Corben doesn’t allow us to hide behind our ideas of what is or even behind Mike Mignola’s stylized shadows that suggest something more powerful hidden where we can’t see it. Corben pulls back those protective shadows and shows us just what is hidden in them. Reading Richard Corben’s work is to look into the heart of horror and to allow yourself to be washed over by it.

Mike Mignola’s Hellboy is there to protect us. From the beginning, Hellboy was the darkness that pushed back against even worse darkness. Behind all of his almost innocence and bluster, MIgnola’s Hellboy is just another working-class hero, a guy punching a clock to go and fight demons even though he physically was one of those demons. That’s the great misstep of those Mignola stories; how much of Hellboy was human and how much of it was demon?

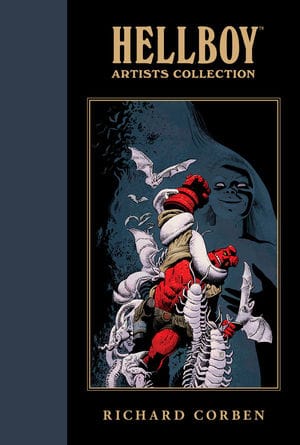

And then in 2006, Mignola got to work with one of his heroes, Richard Corben. Mignola’s writing went to a completely different level of horror. The first few stories, Makoma (2006) and The Crooked Man (2009,) show Mignola doing his best Corben impersonation. These two very different stories feel like they could have been in Creepy or some other 70s horror anthology. Hellboy acts more as a guide or an avatar in these stories that take him into ancient and rural mythologies. Makoma is an ancient hero story where Hellboy is a stand-in for the hero of legend but not the hero of legend himself. Both of these stories, apart from the larger Hellboy cycle drawn by Mignola or Duncan Fegredo (the third-best Hellboy artist,) expand on the world as Corben brings his unique textures to Mignola’s story. Those textures are both visual but also tonal; these are different kinds of stories than Mignola was used to telling. Both stories are 100% Corben as Mignola’s writing here is so informed by the Corben comics that he loved.

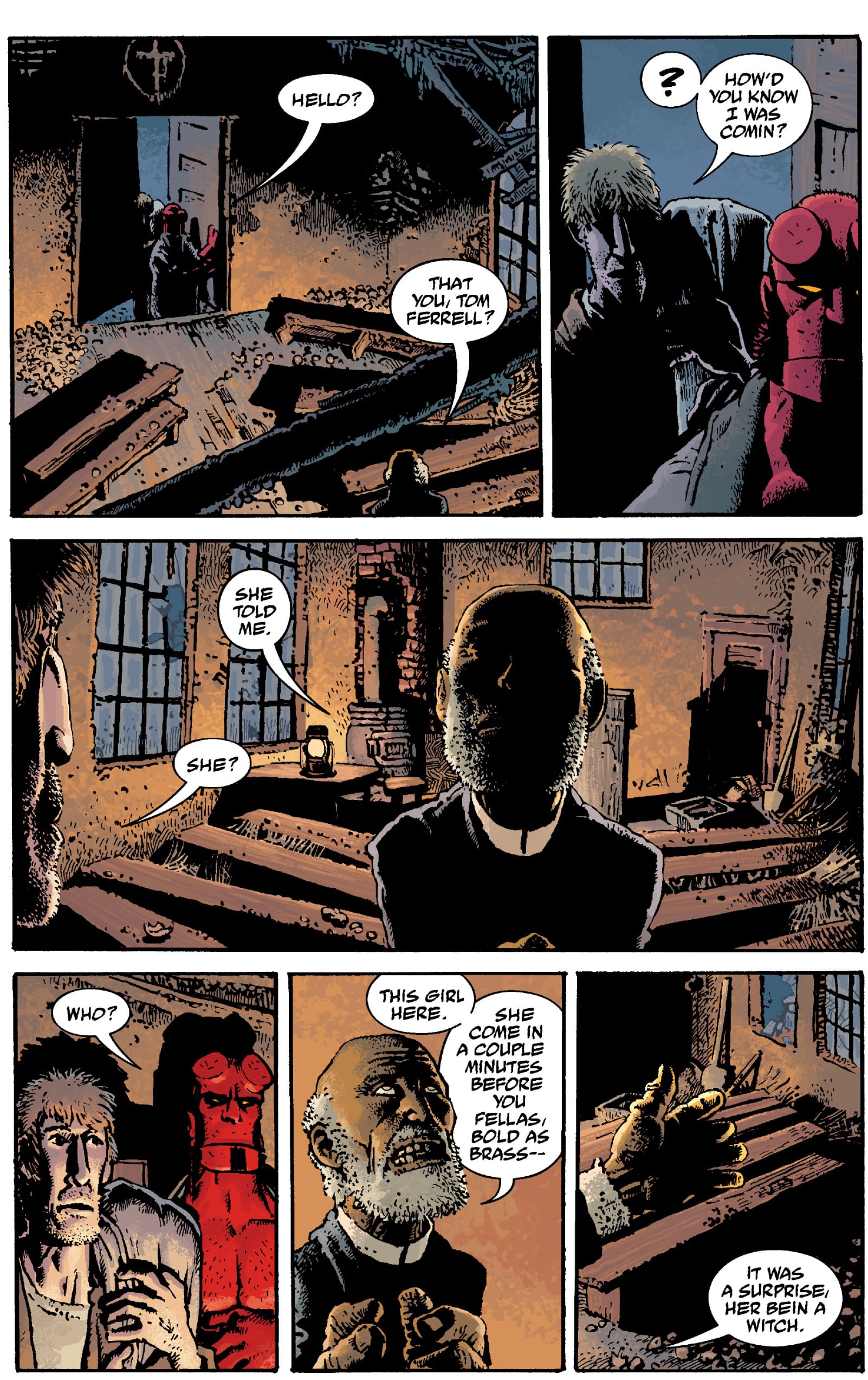

Corben’s characters have a presence to them. This allows him to go from the ancient dusty landscapes of Makoma to the rural backwoods of The Crooked Man as his characters anchor them in the worlds that he draws. In Mignola’s artwork, we never lose sight of the fantastic as that is his focus but Corben’s attention is on his characters and how they tell the story. As Hellboy tracks across Appalachian trails, Corben expresses this weary fear that exists in these woods. You can see in their faces that these regular people have lived with this horror for most of their lives even as they fight to protect themselves from evil forces. Corben’s Hellboy is actually out of place in this story because he’s pretty much just a tourist as he finds people who face temptation and corruption daily.

The fleshiness of Corben’s characters gives him room to have them act on the page. Corben’s faces have always told us so much about his characters and Mignola uses that to tell a story like The Crooked Man that relies so much on these characters having a past and a history to them. Mignola’s artwork is great at taking us to worlds where ancient powers lie in the shadows but Corben takes us to a lived-in world, where men and women struggle against evil. As seen in every Corben face, the struggle is real.

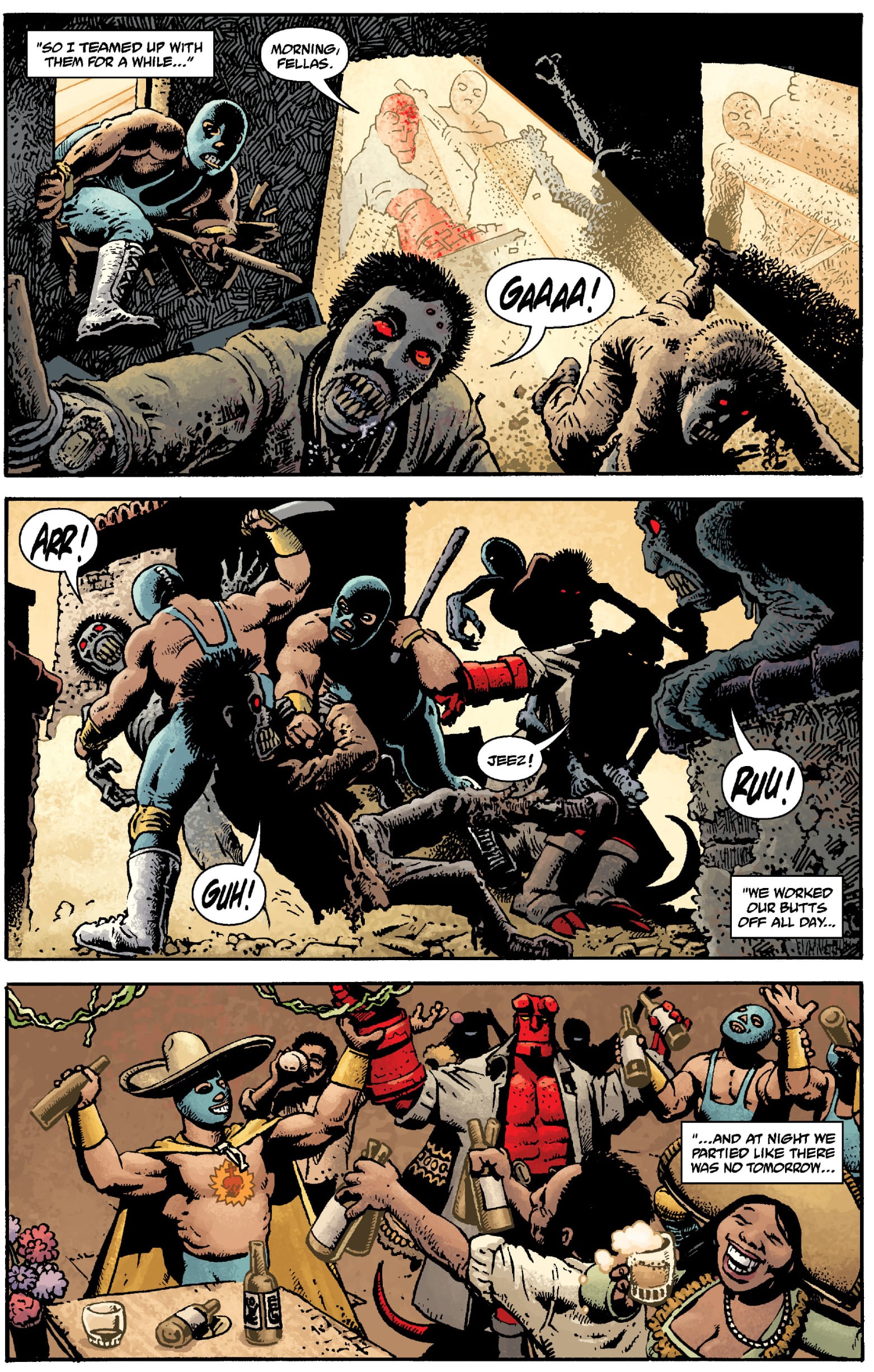

So when Corben gets to Hellboy in Mexico (2010), it feels like Mignola is finally ready to write not just a Corben story, but a Hellboy story. Hellboy in Mexico is the first Mignola/Corben story that feels like it has actual stakes and meaning for Hellboy. This story and its follow up House of the Living Dead, are truly Hellboy stories. Focused on a couple of drunken lost months Hellboy spent in Mexico, Corben is given the room to apply his character work to Hellboy, showing the character at first having the time of his life with 3 luchador brothers fighting during the day and then drinking and partying all night. There’s a life the character has when he’s the main character and not a supporting character that Corben gets to portray. It’s a fun story about Hellboy being Hellboy until the tragedy of the story sets in.

In the short 25-page Hellboy in Mexico, Corben and colorist Dave Stewart move between worlds filled with bad things and worlds filled with evil. Mignola writes a story about finding and losing friendship and Corben’s artwork turns the story into a tragedy that ends up being about the loneliness of the title character. Even as he’s surrounded by fantastical beings, there’s a sense that he’s one of the loneliest people in the world so Corben brings a melancholic tone to this story. From Corben in previous stories, we’ve seen action and horror but now we’re seeing personal drama layered on top of those elements.

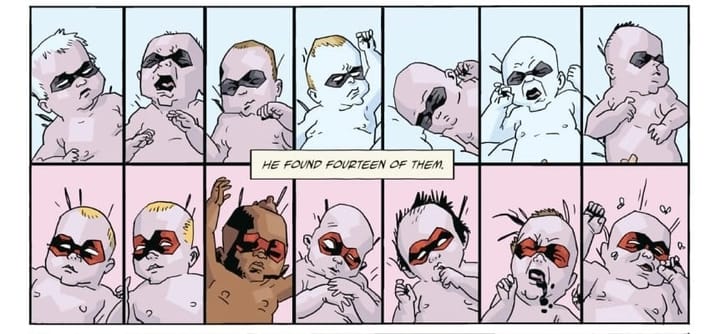

A year later, House of the Living Dead (2011) shows a Hellboy running away from the events of Hellboy in Mexico. This book starts where Hellboy in Mexico ended, with Hellboy remaining drunk and wrestling in Mexican bars. Mignola and Corben show a man even more isolated and alone as he’s surrounded by crowds chanting his name. There’s wrestling, drinking, a wrestling Frankenstein, and Hellboy in this story and Corben makes it all believable and unbelievably sad as he shows these people and creatures fighting against their natures.

The humanity in Richard Corben’s Hellboy work is that it doesn’t try to spare the reader of anything. He can take Mignola’s stories and be faithful to the work that Mignola has already done while charting his path with this character. Corben’s Hellboy is a character searching for his place in the world. There’s a loneliness to these stories as Corben shows a character meeting the supernatural and rejecting it to protect humanity. He’s a man out of phase with the world around him even as he’s completely tied to the supernatural forces that shape it.

Comments ()