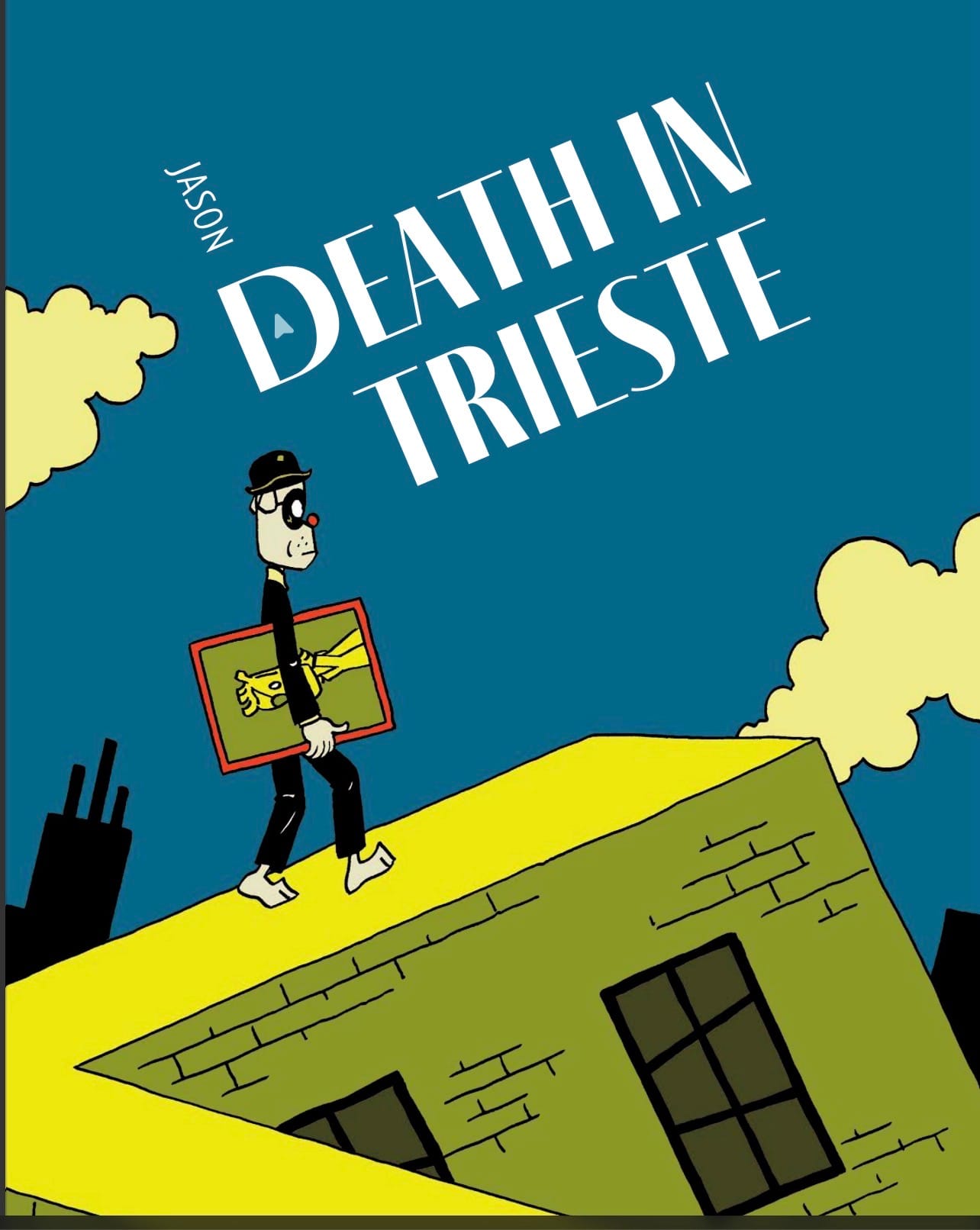

The Rebellious Comics in Jason's Death In Trieste

Jason doesn’t give you any more than he has to and that’s often less than you think you need.

Death in Trieste by Jason (Fantagraphics Books, 2025)

How do you describe a Jason comic book? Do you start with the anthropomorphized characters? The thin lines between history and fiction? The non-interest in easy storytelling? Those are all on display in Jason’s Death In Trieste-, his new trio of loosely-connected short stories. While it seems easy to boil his work down to simple descriptions that frees you to offhandedly quantify and classify his work as something “Jasonesque”, that’s also an abdication of engaging with Jason in any meaningful way. You can write it off as just another Jason book and you probably have an idea of why that means and whether or not that works for you.

Personally, it works for me. I like the distinctive quirkiness of a Jason book. It’s kind of like a Wes Anderson movie—you know going into it what it will be like. Jason has delighted me, entertained me, and puzzled me but in many ways, it’s the cartoonist who has left an impression on me far more than the work has. Maybe it is the quirkiness of his particular mode of storytelling that makes it easy to read, enjoy in the moment, and move on. That’s not to say there’s nothing to his stories but it’s often hidden behind a stylistic veneer that really drives how you engage with the storytelling far more than with the stories themselves.

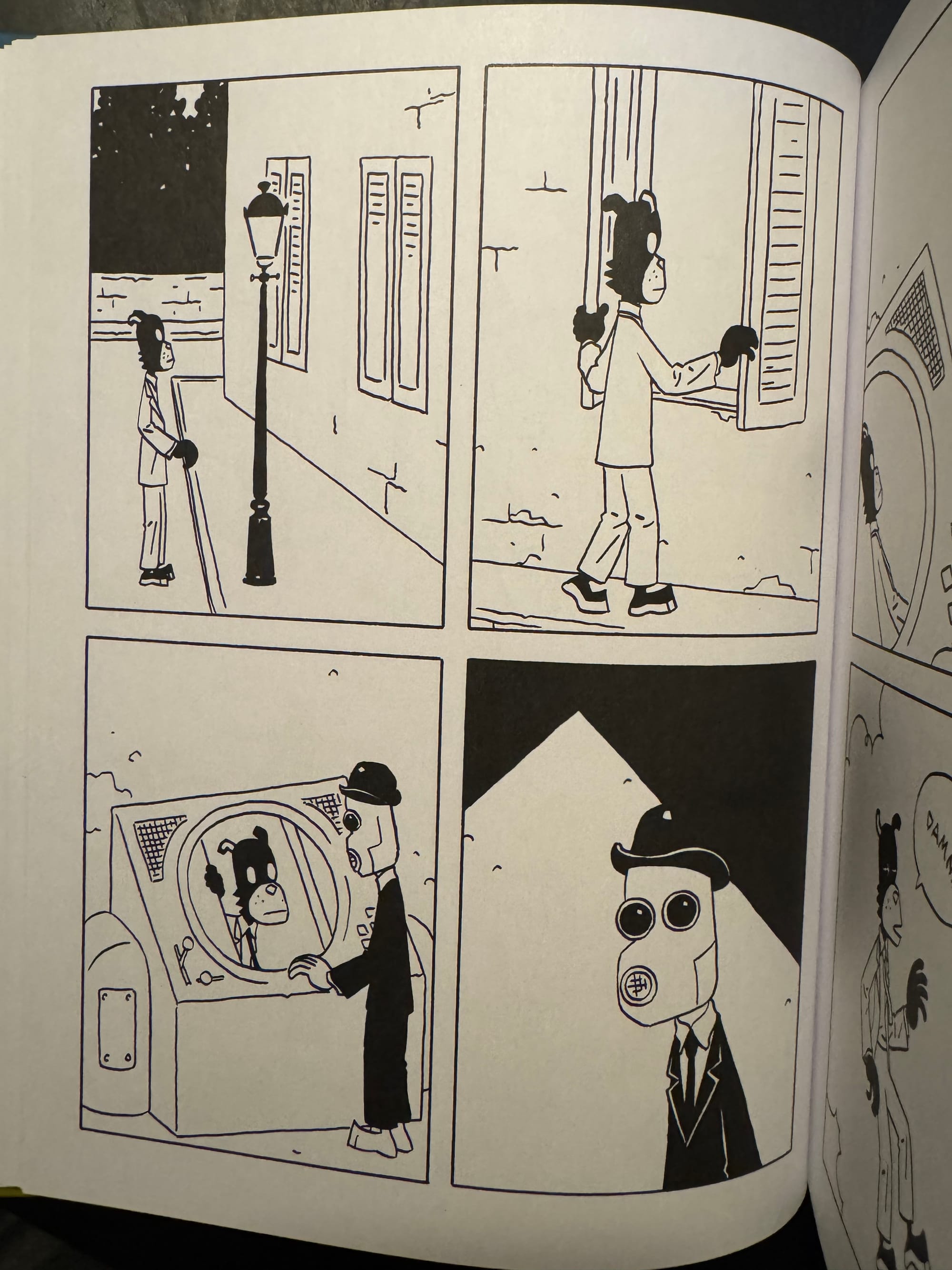

The book opens up with “The Magritte Affair,” a story of two detectives on a case involving “René Magritte-related nervous breakdown(s).” It’s an intriguing introduction to this trio of stories, establishing art as essential (or maybe fundamental) to life. Magritte becomes some kind of virus in this story; a Magritte painting leads to people dressing like the painter as they commit crimes. The detectives operate on a Steed & Peel kind of partnership, playing off one another as they both bring different qualities to their partnership.

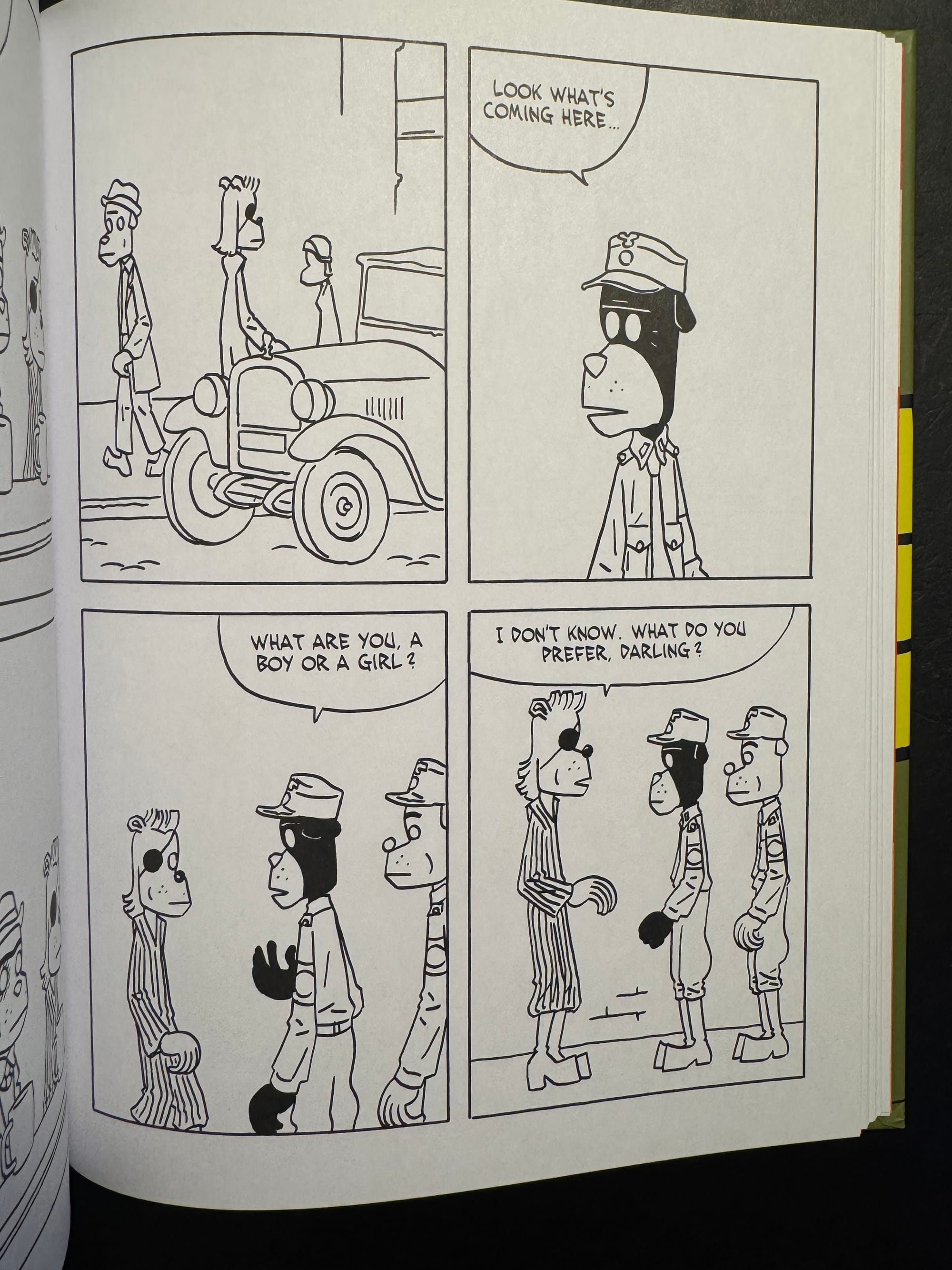

The middle piece, the titular “Death In Trieste” takes place between the two world wars, as Dadaism informs so much of these characters and situations. Jason explores this liminal time of peace where the world is not fully healed from the First World War and not yet prepared for a second one. A time-travelling David Bowie finds himself in a relationship with Marlene Dietrich while a trio of performance Dadaist artists try to find exactly what their act is and Nosferatu haunts the nighttime rooftops of the city. It reads as stream-of-conscious storytelling, Jason following whatever threads interest him on the page.

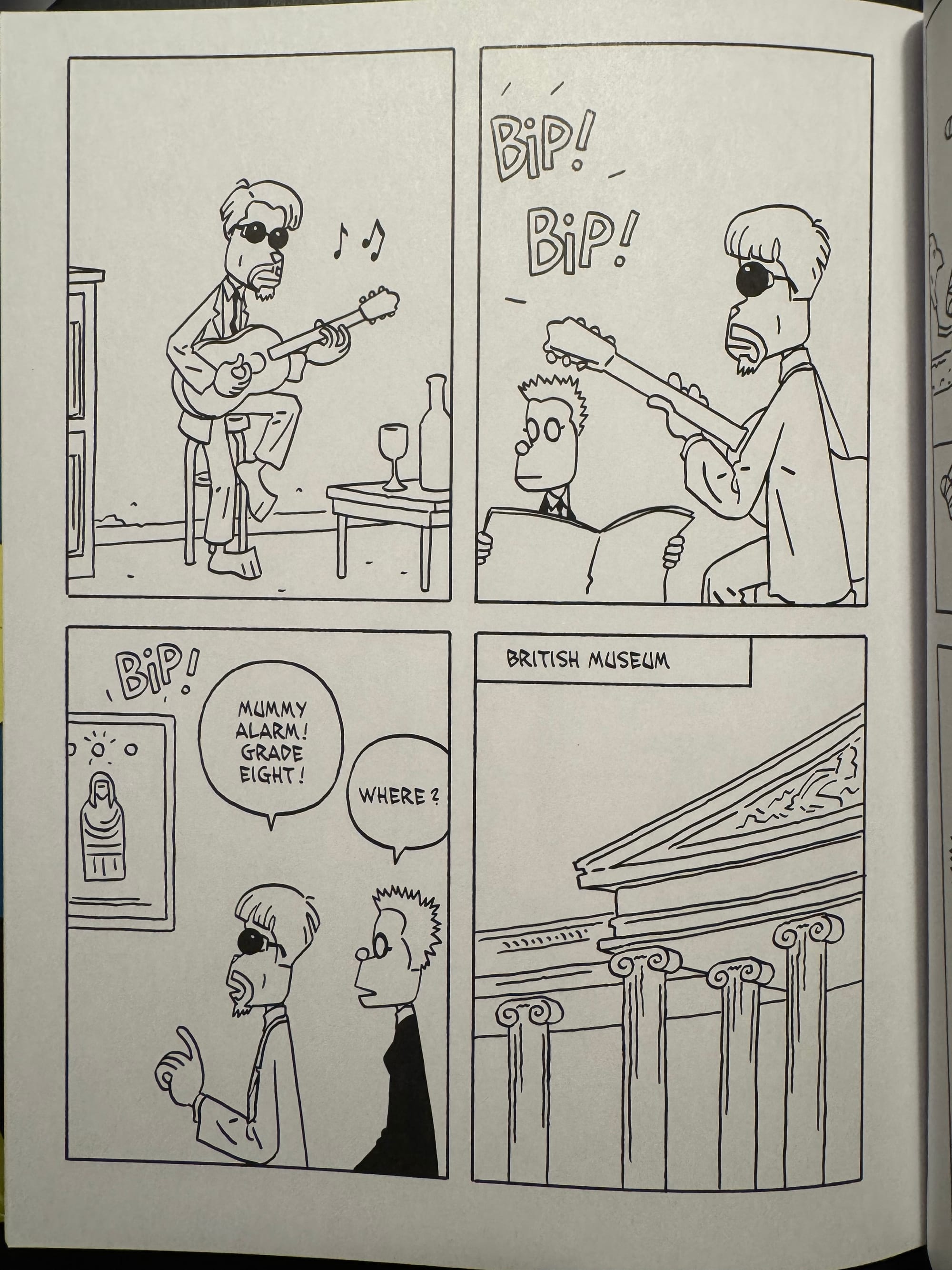

In “Sweet Dreams,” the final story, Jason tells the story of New Age musicians trying to save the world. Like “Death in Trieste” this is Jason working without a net as the story feels even more fragmented and disconnected than either of the prior stories in this book. David Bowie appears here again, tying into “Death in Trieste” but the story reads very episodic as groups like The Eurythmics, Ultra Vox, and U2 each have their own quick adventures at the end of the world as Bowie launches into space to destroy an asteroid that’s mysteriously on a collision course with the planet. There’s even a little bit of Mike Mignola-type monsters in this story.

In each of these stories, we see art in the place of politics, of civil servants, and of any other kind of worldview. Art is the oxygen we breathe Jason seems to be saying. Jason and his anthropomorphic characters live in this world where art is everything and it seems like a better world, or maybe just a more palatable one, even as it faces impending horrors. Just knowing that Bowie or Annie Lennox is out there fighting for us makes the world seem a bit better.

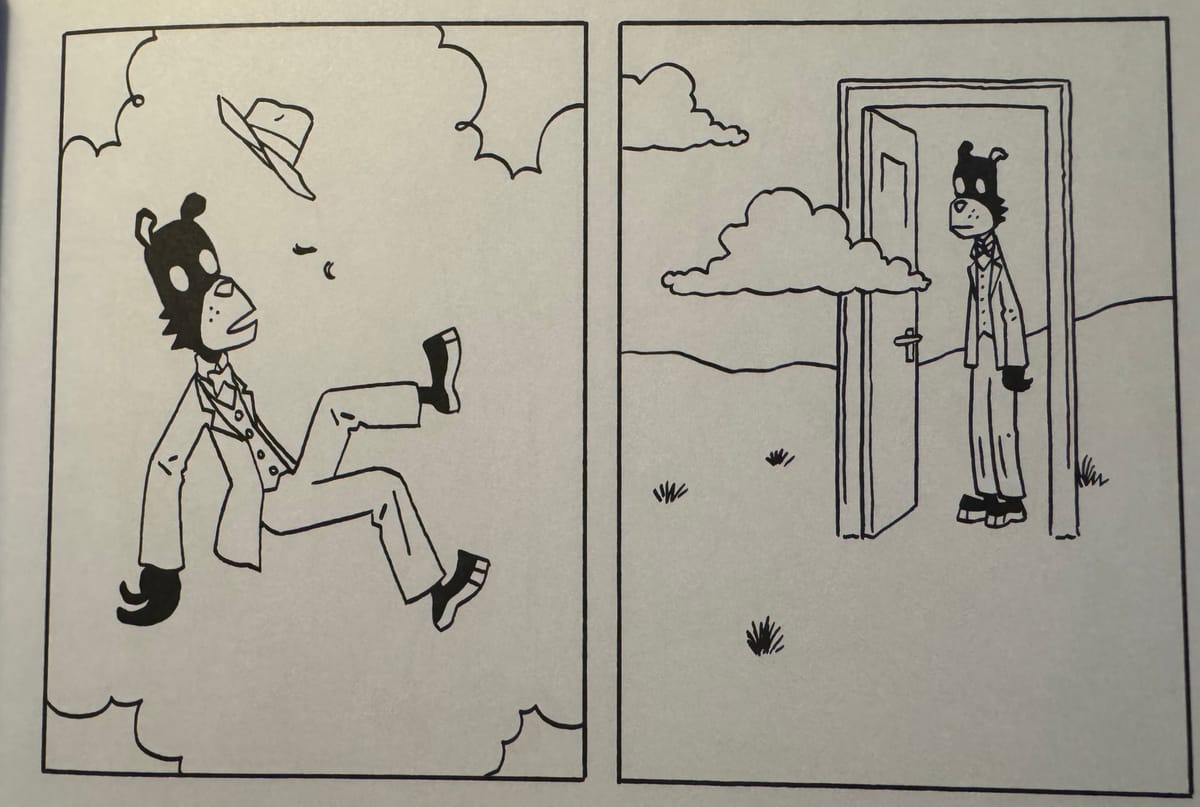

But there’s this nagging question that comes up after you read these stories— what is Jason doing here? These stories are full of characters but they’re not really stories about the characters. It’s hard to find any kind of character growth to latch onto. There are ways that Jason’s stories feel more like just a series of occurrences with little to tie them together. Plot point A leads to point B and point C follows but there’s not a lot in between them. It’s like Jason is interested only in the plot and leaves the gutter space to us to fill in any story we want. Why is Bowie in pre-WW2 Berlin? What’s the connection between 3 Dadaist artists and visions of future Nazi horrors? How did the Eurythmics become secret agents? These are the kind of things other cartoonists would explore to fill out the story, to define character, and to build their worlds.

Instead, Jason is all about the visual storytelling here. The design of his worlds tells us so much of who and what these characters are. Where others would fill the space with dialogue and exposition, Jason strips almost all of that out of his work to tell the stories through the panels on the page, through the images in those panels. What’s in those drawings is what’s important and everything else would just be needless fluff. So the stories feel puzzling even though everything is there but it’s just not as much as we’re used to in western storytelling. It’s very traditional but stripped back to the bare structure.

That’s the puzzling nature of Jason stories— he doesn’t give you any more than he has to and that’s often less than you think you need. The trio of stories in Death in Trieste are pure Jason, stripped of anything that gets in the way of him just telling these stories of art, history, and the dread of the end of the world. These aren’t stories to read because you want to read about characters and their feelings; they’re stories that you read because you have the same need to read them that Jason has to draw them— that almost primal need to be living in the world of art and pure story.