Rick Veitch's The One: A Cold War Comic Reflecting Today's Superhero Culture and Humanity's Struggle for Unity

Rick Veitch's The One challenges the notion of superhero power, reflecting the failures of a broken world.

“Nothing ever ends, Adrian. Nothing ever ends,” the being once known as Jon Osterman says before disappearing into a three-dimensional model of a solar system. A portion of New York has just been obliviated by a man once worshipped as the hero Ozymandias and the being who had the most power to do something about it just fades away.

Kicking a Kryptonite-infected Superman in the face with a spiked boot, Bruce Wayne growls, “I want you… to remember, Clark… in all the years to come… in your most private moments… I want you to remember… my hand… at your throat… I want… you to remember… the one man who beat you…” right before Wayne’s heart gives out and flatlines.

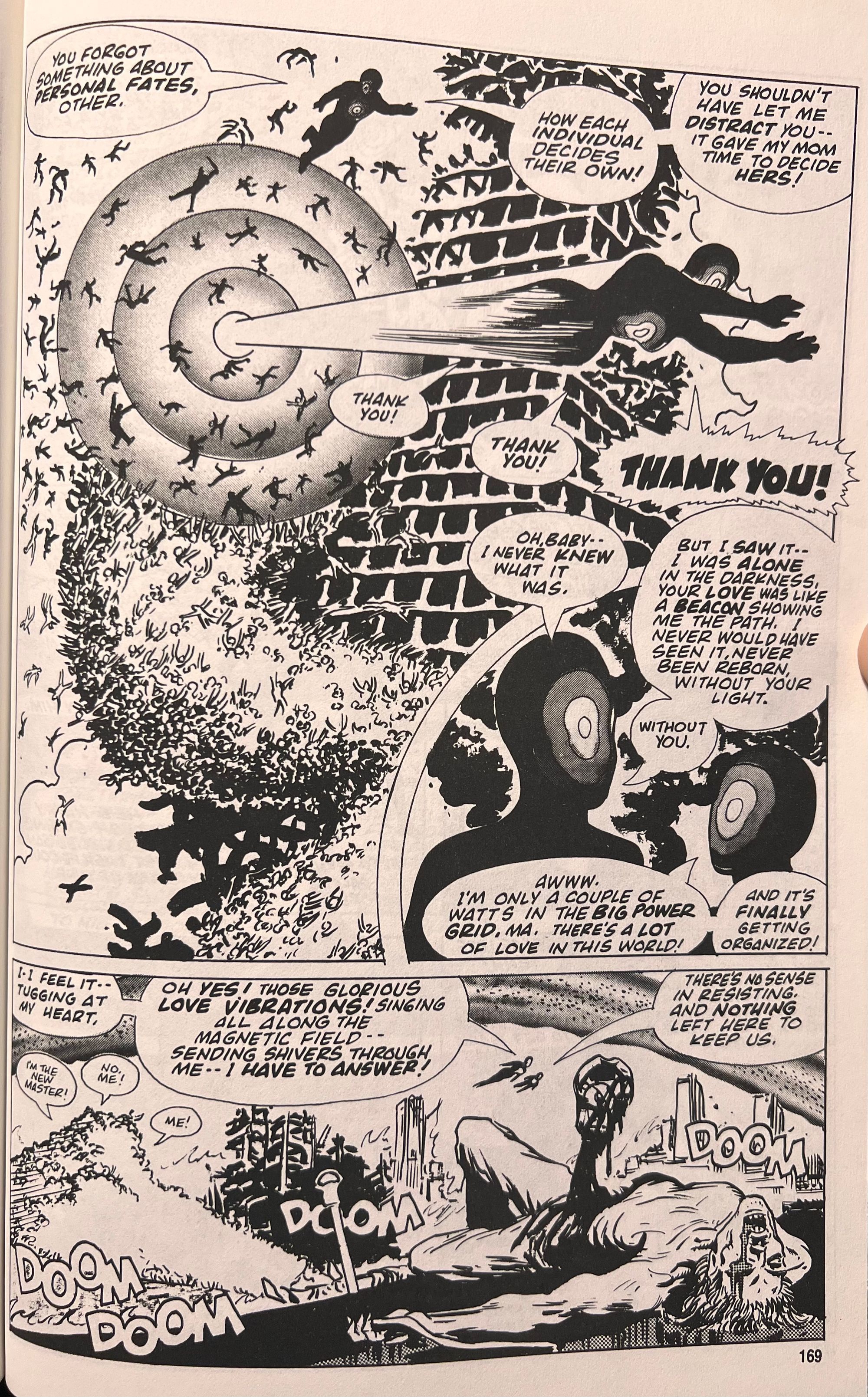

In some kind of heaven, the naked, cherubic, enlightened survivors of a corrupted world are serenaded by four lads from Liverpool singing “We all live in a yellow submarine, a yellow submarine, a yellow submarine.” And thus ends Rick Veitch’s The One.

These are the 1980s texts that ushered in the age of superhero revisionism in American (read: DC & Marvel) comics: Watchmen, The Dark Knight Returns, and The One. Two of them are still considered classics today but the third is the type of comic that you almost had to be there for. Or at least, you have to know what Moore, Gibbons, and Miller we’re doing to see how Rick Veitch is having a discussion with them in The One. In the 1980s, we were just far enough from the 1960s to still have some of that idealism infecting us even while we were cynical enough (or maybe realistic enough) to believe that at any moment we were doing to die in nuclear annihilation. For those of us who were teenagers at the time, it was comics like those by Miller, Moore, Gibbons, and Veitch which expanded our worldview with their pessimistic take on our superheroes and our gods which guided us through school, puberty, teenage rebellion, indoctrinating us into a mistrust of the powers which ruled our world.

Looking back now, you can see these comics as trying to radicalize their audience into identifying the failures of their and past generations who mistakenly thought they fought the war to end all wars. They were identifying their own generation’s mistakes in viewing Superman or Batman as great Americans which we should all try to be like. These false idols were the stories of our youth, the golden gods until these creators tried to take them down a notch or two.

And at the time we thought these new texts and their worldviews were just cool comics.

Rick Veitch’s The One is a Cold War comic, pitting the godly Americans against the godless Soviets with superheroes as those governments’ weapons of mass destruction. The superman is more powerful and deadly than the atomic bomb in Veitch’s estimation and maybe it is because we were stupid enough to believe that we could control that much power. We’re Americans; we have might on our side thanks to our righteousness and our goodness. That’s what it came down to during the Cold War, wasn’t it? And that’s what a lot of us still want to believe our country is. The greatest country on Earth. Yeah, right.

Veitch replaces the bomb with superheroes– the Americans have the brother/sister duo of Charles and Amelia, good kids given powers beyond imagining– Superman and Supergirl if Supergirl were supposedly his sister instead of cousin. The Soviets have their Bog, a superpowered god for a supposedly godless people. These patriotic “heroes” supposedly represent the best of what these different ideologies offer but they’re just that– mouthpieces and fists for powerful men who have different thoughts about how the world should run. There are many ways to read what Veitch is doing with these characters, from the clearly political (US vs. USSR) to the meta (a bit of Marvel vs DC, anyone?). Like Miller and Moore, Veitch is fascinated by the overindulgence of superheroes, telling this tale back when Rolling Stone magazine declared that comics weren’t just for kids anymore. This is superhero comics for people who want to have nightmares about superheroes.

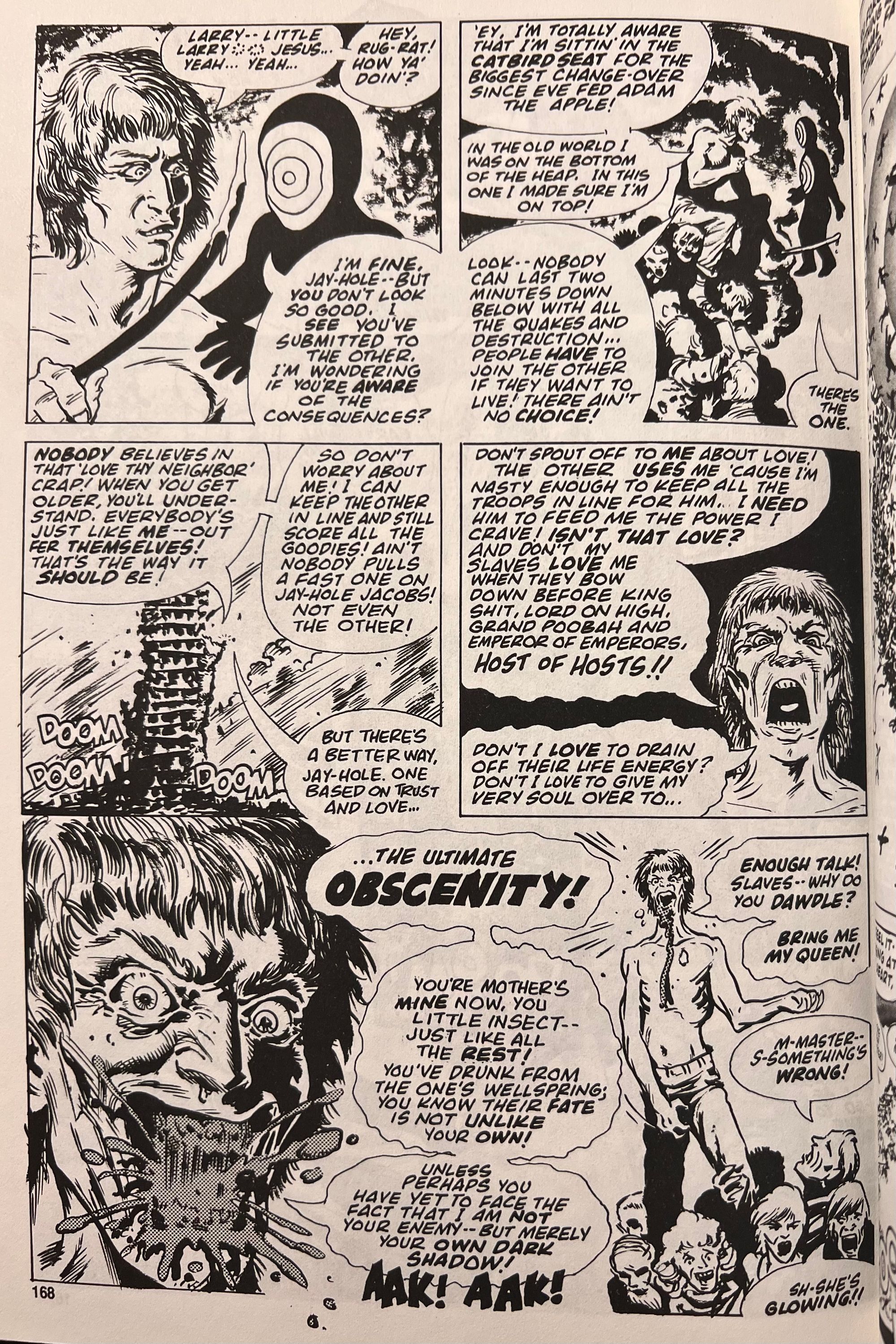

You can draw a straight line from Veitch’s The One in the 1980s to Mark Millar’s work, specifically The Ultimates, with its contempt of the nationalized superhero. But Veitch offers a fascinating counterpoint to Charles, Amelia, and Bog with The One and The Other, two opposing forces that work on a more human level than politics. The titular The One is a black bodysuited with a series of concentric circles on his face and chest. If there’s a hero in this book, it’s The One and his message of unity and togetherness. The best of humanity brings all of us together as The One. The flip side of that is The Other, a mass of human bodies, each person trying to claw their way to the top in their selfish needs to be to have and be everything. The One is humanity’s connections while The Other is mankind’s cruelty and corrupted individualism.

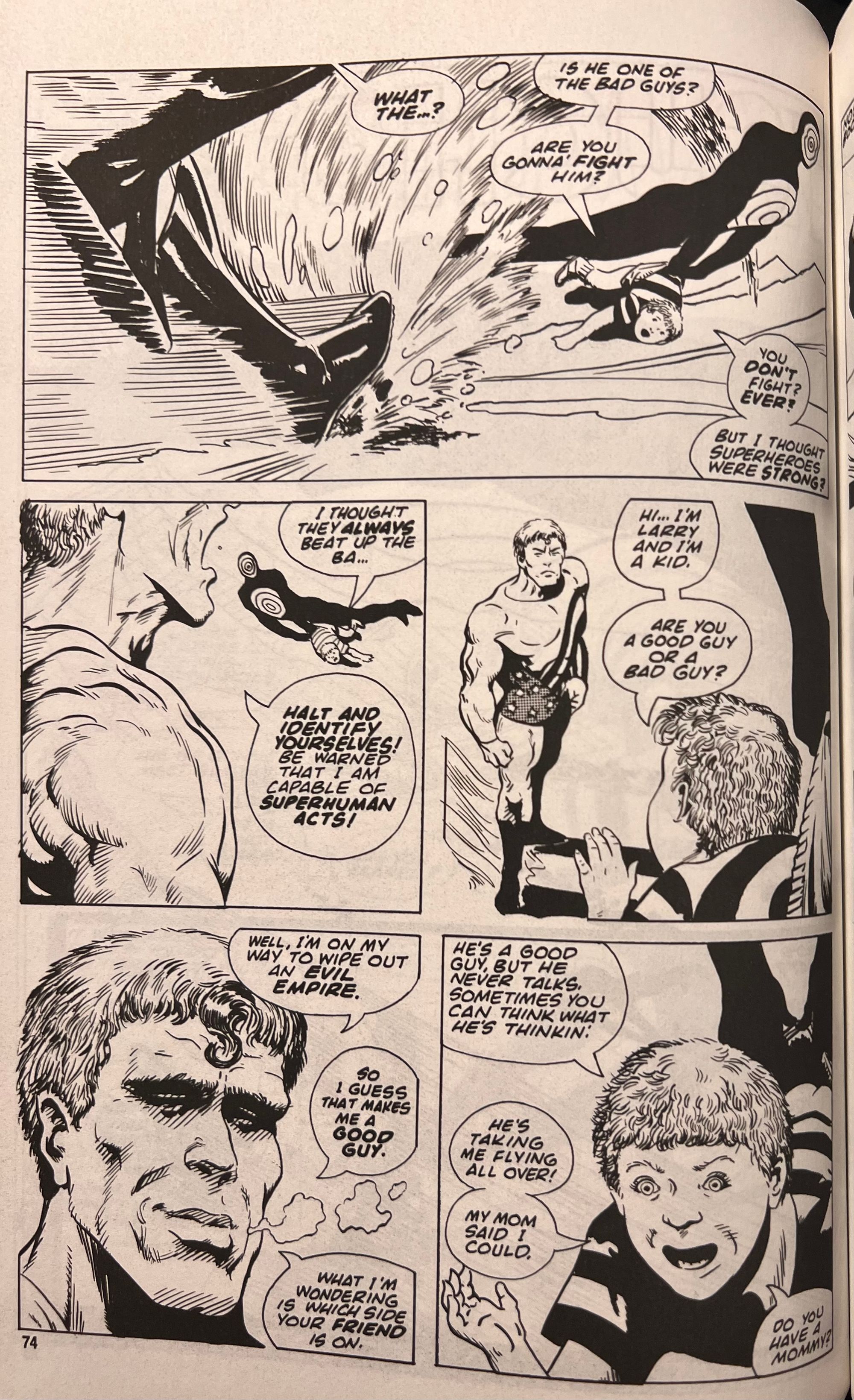

The so-called superheroes operate on The Other’s level in their Cold War battles, seeking power and pleasure over all else. To bring The One’s story to life, Veitch focuses on a small group of people, a mother and her son, and their interracial couple, one of who just happens to be an honest-to-goodness 1960s hippie. The son, Larry, is the innocent child in this story; he hears and instinctually understands The One’s message. His mother Egypt is ultimately the conflicted character in this book, caught between The One and The Other (get it?), trying to find some kind of equilibrium between looking out for humanity or her own selfish pleasure.

The One is Egypt’s story; everything else is set up to illustrate or reinforce the struggle that Egypt experiences. The battle of the superheroes is what the world of The Other looks like- fighting essentially for the sake of fighting. That’s a world of might makes right. It’s every Mark Millar book ever. Every. Single. One. Larry becomes the host of The One, bringing his unconditional love to the world. That’s the dream of the superhero. It’s Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely’s All-Star Superman, decades before that book came out. Veitch combines these differing viewpoints of superheroes to try to show us a view of what superheroes are and what they can be. They’re the decadence of the 1980s writ large but they can also be the hope for the future. The potential for both is in the idea of the superhero back then.

Here it is almost 40 years later and we’re circling back around these ideas as thanks to pop culture, the idea of superheroes is more popular than ever. Superheroes have dominated pop culture for the past 15 years the way that they dominated comic culture back in the 1980s. It’s the same cultural thirst for these ideas just with an insanely larger audience. Everything old is new again.

The 1989 King Hell black-and-white version of this story depicts a world that’s at the end of its life, corrupted by greed at nearly every level. It takes a character like Larry to remind us that there is some innocence in this world. Veitch’s drawings are dark, inky, over the top, and repulsive on a narrative level. His depiction of these physical and spiritual battles is designed to be another reflection of the failures of this world and our dreams. In his view, there is no difference here between the hero and the villain– it’s all about the powerful and the powerless and that’s how his art depicts everything. Well before Christopher Nolan’s Batman, this story is showing how you either die a hero or live long enough to become the villain. And nearly everyone here is a villain.

The One turns out to be as relevant if not more than it was originally in the 1980s. Superheroes are everywhere; we’re pretty much at war with Russia, and there’s a distinct lack of empathy in the world as it’s every man, woman, and child for themselves. We’re living in the 21st century and it’s still a battle between The One or The Other. Now if anything, Veitch’s ultimate answer to everything seems a bit simple and naive. In the end, there’s still The One and The Other, with The One’s enlightened people giving up on the Earth to go and live in some heavenly realm while the Other’s mass of humanity still just slouches around the Earth. That’s how we supposedly win in The One, but there’s no angelic superhero coming to rescue us and take us off to a better place.

Comments ()