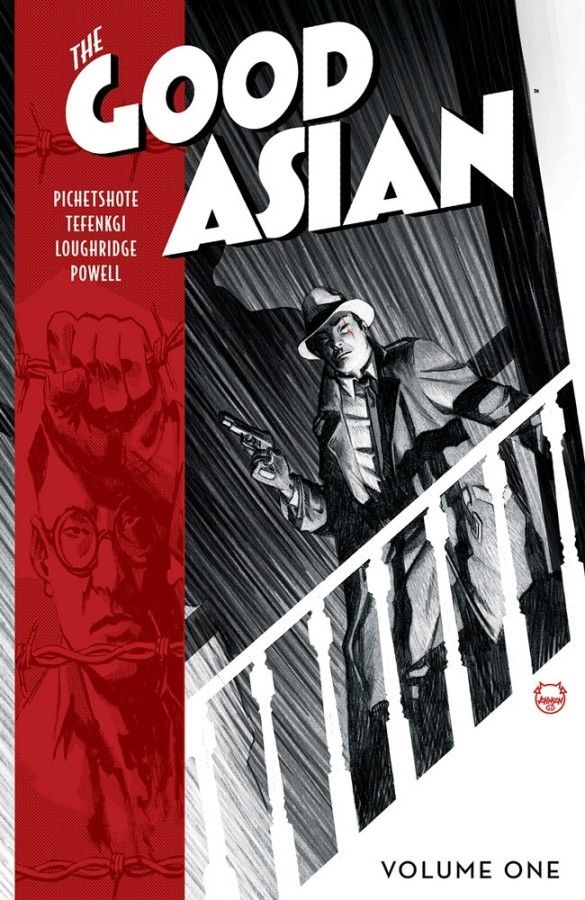

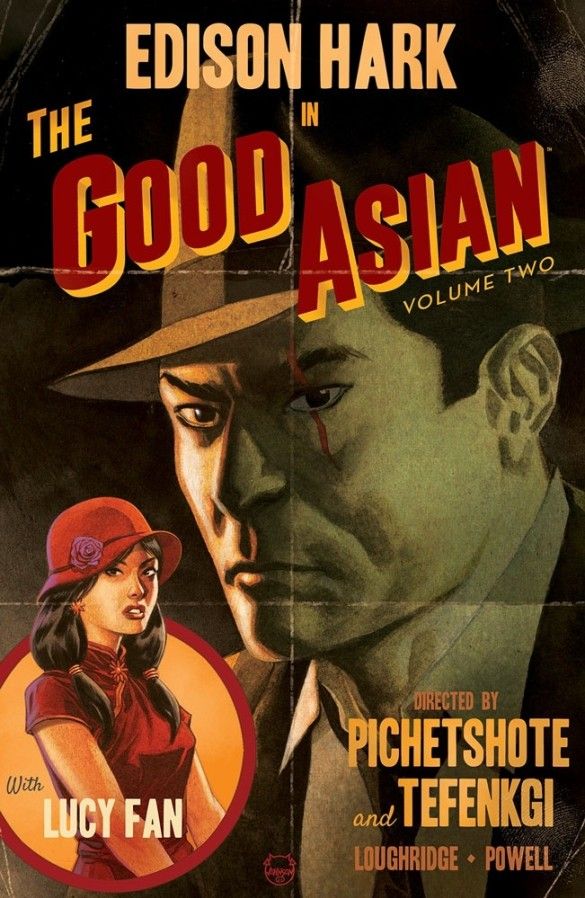

Playing By The Rules in Pornsak Pichetshote and Alexandre Tefenkgi’s The Good Asian

If any book can live up to the legacy of “Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown,” it’s Pornsak Pichetshote and Alexandre Tefenkgi's The Good Asian.

Edison Hark is a man out of sync with the world around him. The young detective, born to Chinese parents but raised by a rich American family after his mother died, isn’t enough of any one thing to be accepted fully into any world. He’s not white so he doesn’t enjoy the privilege that the children he was raised with do. His Chinese heritage means that he’s just a cop working in San Francisco’s Chinatown beat but he’s not a real cop to the rest of the force. And being the “Chinese cop” in Chinatown means that he’s just another cop, a sellout trying to be whiter than he is. In 1936 San Francisco, he’s a man without connections, walking through many different worlds but not a part of any of them. But when a missing person case brings these different cultures together, they all look to Hark to solve the case. In The Good Asian Volumes One and Two, writer Pornsack Pichetshote and artist Alexandre Tefenkgi use this period and its anti-Chinese biases to examine the weighty subject of immigration that we still face today even as they weave together a tight page-turner of a mystery.

As if to signify just how out of place he is in nearly every situation, Tefenkgi draws Hark like he’s playing the role of a detective in a movie. Hark’s wardrobe looks to be borrowed from nearly any Humphrey Bogart film, taking Bogie’s overcoat and fedora to look like he’s a detective as if he’s playing the part in this story. There’s something almost childish in Hark’s appearance during much of these comics like he’s a kid who’s wishing that he was an adult in this world. Maybe it’s playing too much with my own biases but Tefenkgi is signaling something here through his art, whether he’s implying it or I’m just inferring it. Being a detective is a role that Hark plays, much like he’s played different roles throughout his life.

And if more emphasis was needed on the “detective costume” that Hark wears, Hark recruits Frankie, his best friend whose house Hark grew up in, to role play as a detective and get into places and get answers that Hark can’t. Frankie’s a gweilo, a white man, so he can move around San Francisco a bit easier than Hark can. The two men grew up together, they’re practically family. That’s why Frankie reached out to Hark to investigate a missing Chinese woman who means a lot to Frankie’s father. They should be family but there’s always something present in their relationship to remind Hark that he’s the poor Chinese boy that the rich Carroway family took into their home.

The story starts as a search for a missing girl in San Francisco, just another poor Chinese girl who’s disappeared but as Pichetshote and Tefenkgi delve deeper into this Chinatown, they explore the power structures in place and how everyone has their role in it. Hark may be the ultimate outsider but he’s also one of the only characters in this book who understands their place in this city; as he’s not a part of any particular clique here, he maybe has the clearest view of who’s who here. And even then, his vision is clouded by his own biases towards nearly everyone else. His history with the elder Carroway, Frankie, and Frankie’s sister Victoria turns out to be his blind spot, that thing he’s not able to see around. Even as he’s tried to put the past behind him, the powerful family that raised him are some of the people who are hiding the most from him.

Set in 1936, there may be an inclination to write off aspects of this story as “well, that was then…,” particularly the times’ attitudes and legislation to “control” the Chinese population in America. But that’s the danger that this book acts as a warning against— taking people at a face value and devaluing them for that. Hark is the poster boy for this as everyone reads into him what they want to but he’s as guilty of it as well, largely blinding him as a detective for most of this book. It’s only when he can start seeing beyond his own thoughts and impressions that he’s able to begin seeing the workings of Chinatown and how his case ties into the larger machinations of this San Franciscan enclave.

There’s danger in seeing the world only on a surface level, acting only on skin tones and facial features that are all too easy to use to categorize people. It was true in 1936 and Pichetshote and Tefenkgi are reminding us through their story how true it is today. By being a man without a people to call his own, Hark shows us how easy it is to be both the victim and the guilty one here, getting lost in our ideas of who or what a person is without getting to know them. All great detectives have some flaw to overcome that blinds them to the truth; Hark’s is that he’s as blind to the world as the world is to him.

Comments ()