Lost Reflections on a Photograph in Paco Roca's Return to Eden

In Paco Roca’s new book, each generation just wants to see their mothers smile.

More towards the end of her life than the beginning of it, Antonia moves in with one of her adult children. Once a child of post-Civil War Spain, her parents and most of her siblings have already died; all Antonia has is a picture of her, her mother, one of her sisters, and her two brothers taken at a Spanish beach back in late 1946 at lunchtime. Her older sister Amparín insisted that they have the picture taken as she was about to tell her family that she was engaged to get married. It was a way to commemorate the moment, a nice keepsake of the day at the beach. And then 75 years later, as Antonia moves in with one of her sons, she can’t find the photograph; it was lost or misplaced in the move. Since the picture was taken, Antonia always kept it on the nightstand by her bed, protected under a pane of glass. Paco Roca’s Return to Eden uses that missing picture to explore his mother’s childhood, her relationship with her parents, and with her brothers and sisters. It’s the story of a son trying to understand his mother but even more to understand the moment of that picture and what it meant to his mother.

A companion piece to The House, the book where Roca tried to figure out his late father as they cleaned out his house after his father’s death, there’s a mystery about his mother and her attachment to this photo. Out of everything that his mother could long for as she moves out of her own home and in with one of her children, it’s this picture that means everything to her. This was one of the earliest pictures of her that was ever taken. The first was from when she was a young girl with her oldest sister and her fiance, a “typical studio portrait, in which the betrothed pose in their nicest outfits, gazing with feigned interest at a point outside the frame.” The second photo was years later when Antonia was working as a nanny, together with the girl she was caring for on a toy horse. Interestingly, Roca includes both pictures in his comic (as well as the eventually found missing one.). His mother had kept both of those all that time but they weren’t treasured nearly as much as the one from that day at the beach. They didn’t sit on the nightstand by her, watching over her as she slept.

There’s a story behind this photo, a meaning to it. When it was lost, Roca didn’t understand what it meant or why his mother shut down the way that she did. To Antonia’s son, it was nothing more than a photo, a memento of a day at the beach like so many others that his mother must have had in her childhood. But for his mother, it was her life reflected in that picture, it was her family. Return to Eden isn’t telling a parent’s story the same way that something like Art Spiegelman’s Maus did, where that book and its story existed both in the present and the past. It was about Spiegelman learning about his father as much as it was about his father’s story. In Roca’s story, we don’t see the investigative portion of it; Roca isn’t actively trying to find out about his mother’s life as he is telling us about it.

We don’t know how Roca learns the meaning of this picture; his mother isn’t telling the story of it. It’s some omniscient narrator that’s telling us about Antonia's Life. So Return to Eden isn’t investigating the story here as Spiegeman showed in Maus. Antonia’s life is the story here. It has a beginning and ending that’s encapsulated in this photograph of a family spending a day at the beach. It was where she came from. It was the life she led. It’s where she went with her own family. It’s the dreams that she had for herself, her sisters, her children, and her mother.

So then the pain of Return to Eden becomes something different- it becomes more personal and direct as we develop this relationship with Antonia and live this childhood with her. (That’s not saying that there isn’t pain in something like Maus but we experience it in a different way than we do in this book.). Roca doesn't put up any barriers between the reader and Antonia. The story is told from this omniscient perspective, able to see through time and even space, as she has these family relationships and the breakdown of them. Starting with Antonia’s parents, Roca just shows this crumbling through a couple of generations of a family and the bonds that connect them. This picture though is the unbreakable bond between these generations, tying Antonia’s parents to her children as a continuity of blood and pain. Roca shows his mother as a woman surrounded by pain. The photo is practically the epicenter of her pain and yet it means everything to Antonia.

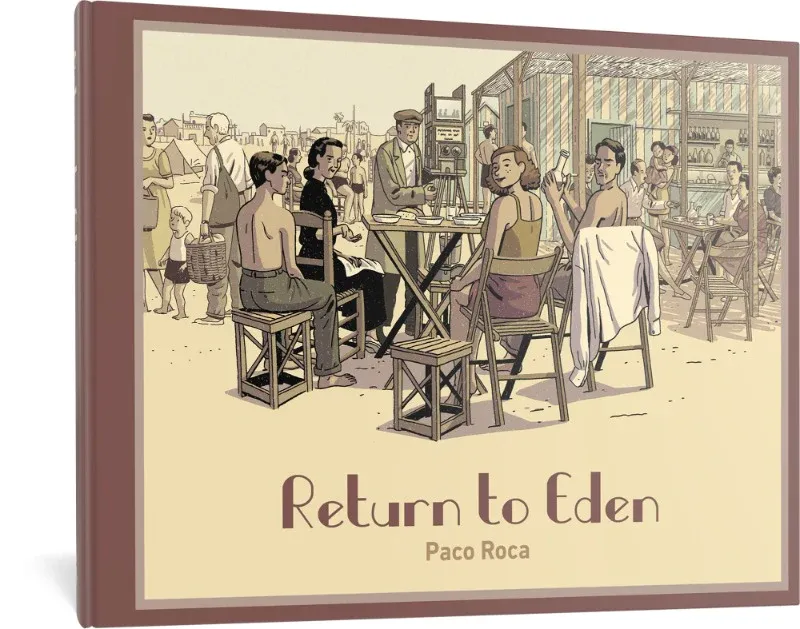

The cover of this book then becomes an interesting portion of this story, showing a moment either just before or just after the picture was taken that doesn’t line up with the sequence of events as shown in the story. Within the narrative, the picture-taking is tense; the father isn’t there (and hardly missed,) the sister wants to share some good news and is emotionally cut down by one of her brothers before she can, and Antonia’s mother just looks tired through the whole thing. But that’s not the image on the cover; while the brothers look like they want to be elsewhere, Antonia has stepped back from the table, viewing her sister and mother turning towards her with smiles on their faces. It’s hard to find any image in the book where her mother was smiling but there it is on the cover– a blink-and-you'll-miss-it smile.

In the story, Roca revisits what that day could have been. A day where after the picture was taken, the family enjoyed the day and laughed together. He reflects on how that imaginary day could have impacted Anatonia when she had her own family at that beach, where she was the mother enjoying the day with her husband and children and having their picture taken. It’s a moment where you can see what was and what could have been in that moment. For Antonia, that picture from a day at the beach was the world to her, a relic of that family as well as a reminder of what a family should be.