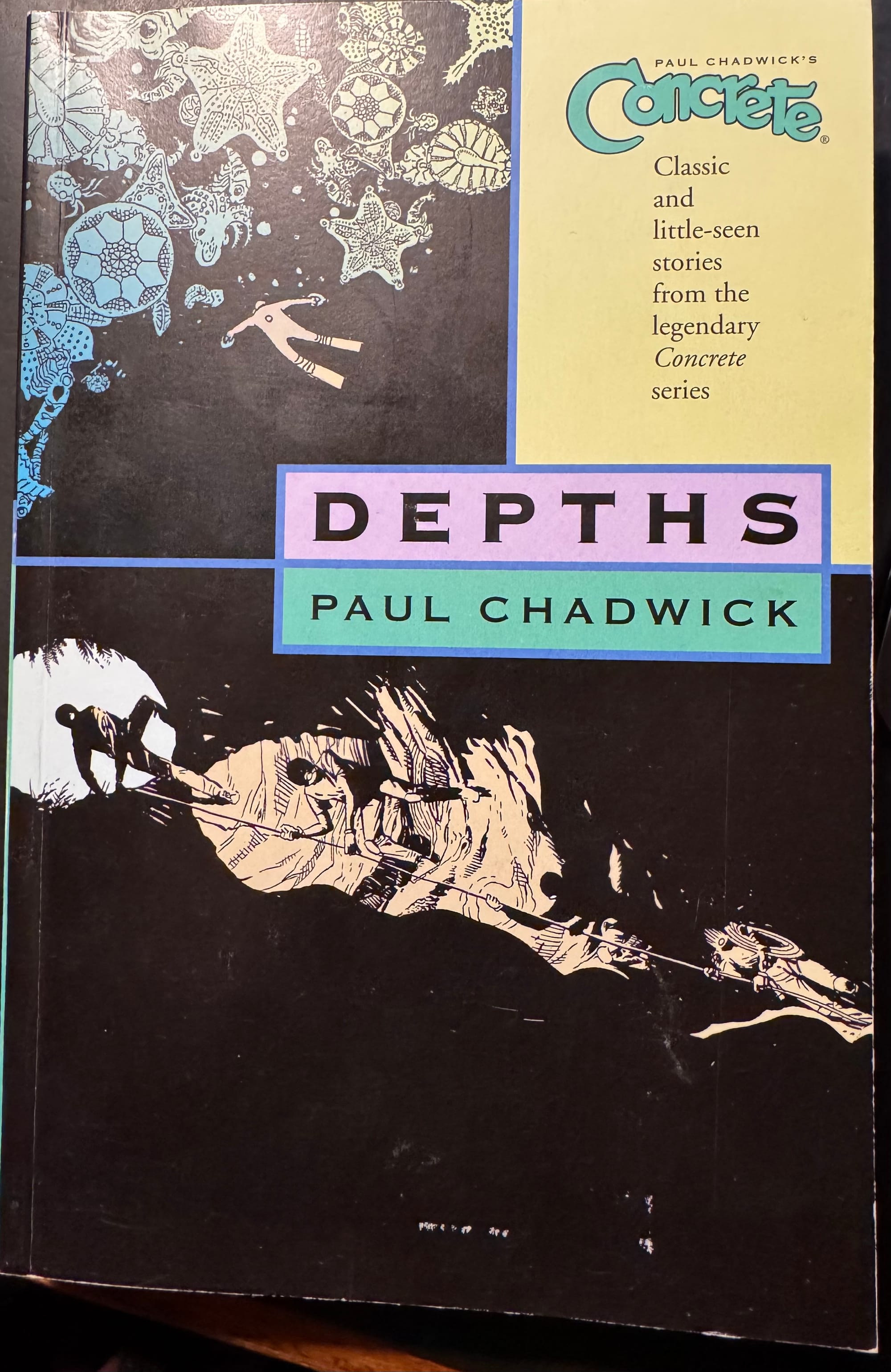

Taking the Plunge into Paul Chadwick’s Concrete: Depth

The story of a man whose brain has been put into an alien body is the stuff of B-level science fiction, the b/w movies that we used to be able to watch on Saturday afternoons. And there’s plenty of that in Concrete: Depth but it’s not the only type of story that Paul Chadwick wants to tell.

Concrete is a superhero. He has a secret identity. He has an origin involving body-swapping with aliens. He goes on adventures. Imagine Marvel’s The Thing, but instead of Ben Grimm being an adventurer, he is a slightly overweight speech writer for a congressman and you’ll get the basic concept behind Concrete. Back in 1986, super-heroes ruled comics; there were a few offshoots like Love And Rockets but the publisher Dark Horse was trying to find ways to expand that in the wake of the black & white comic explosion birthed by The Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. Dark Horse’s most obvious attempt to get into the conversation was James Dean Smith’s fun but forgotten-to-age Boris The Bear, which was a parody of TMNT, which itself was a parody of Frank Miller’s original Daredevil run. Boris the Bear’s first cover was a parody of another Frank Miller book, Elektra Assassin. So Boris the Bear was on Dark Horse’s frontlines as they snuck Paul Chadwick’s Concrete onto comic shop shelves through the first issue of their anthology Dark Horse Presents.

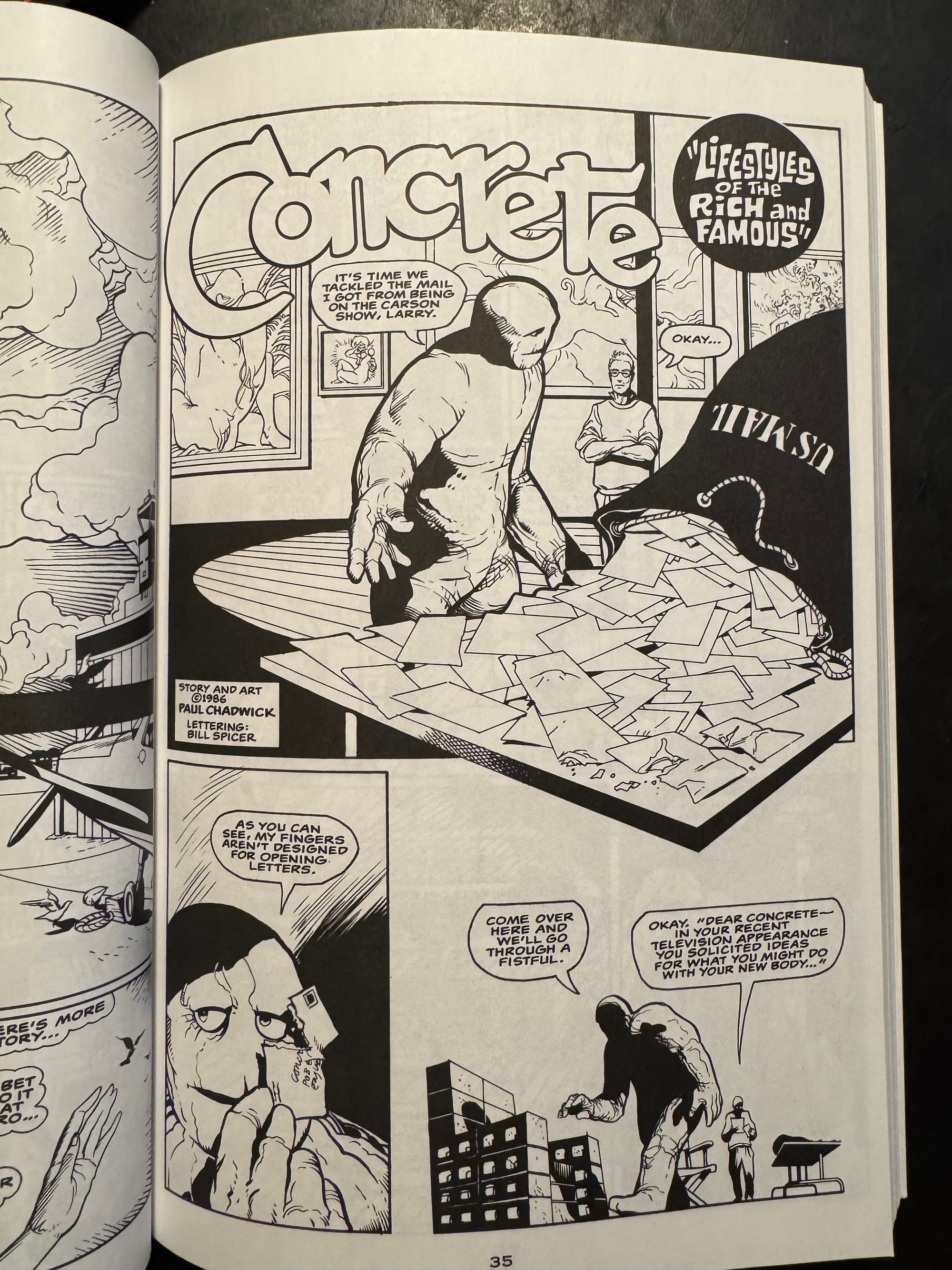

Paul Chadwick started out doing storyboards for movies (Strange Brew, anyone?) and did a handful of Dazzler comics for Marvel before DHP #1. The first Concrete story, “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous,” started right in the middle of things. Concrete and his assistant Larry dig through fan mail he received after an appearance on the Carson Show (remember, this was back in 1986.) On that show, Concrete asked the television audience to send him ideas of what he could do with his amazing body. One of the letters invites him to a fancy party, offering him $1,500 to mingle with the rich and famous for a few hours. Easy money, right? The “exclusive party” turns out to be a kid’s eighth birthday party, thrown by a suburban mother who was just trying to make her son’s birthday extra special. There was no $1,500 and no fancy hobnobbing. Welcome to the world of Paul Chadwick’s Concrete!

While the 2005 collection Concrete: Depths includes “Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous,” it begins instead with Concrete #1, which came out in 1987. This story sets up some of Concrete’s “backstory,” the public story that he was a declassified military experiment. In that first issue, he’s called upon by his former boss to help rescue miners trapped in a collapsed mine. Concrete: Depths began a series of books that collected Chadwick’s story in chronological order instead of publication order. It wouldn’t be until Concrete #3 (also in this collection) that we would get the real story of Ron Lithgow, the speech writer abducted by aliens.

The stories in Concrete: Depths are still some of Chadwick’s earliest Concrete stories, with one or two late 1990s stories also included here. In Concrete, Chadwick uses the language of superheroes, adventure stories, and science fiction to explore the world of an ordinary man who becomes something extraordinary. This is a few years before Kurt Busiek’s Marvels or Astro City, which would explore some of the same themes- ordinary people in an extraordinary world. Or maybe Concrete is more of a reaction to Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons's Watchmen, with its what-would-superheroes-be-like-in-the-real-world approach, tracking along a less sensationalistic path than Watchmen does.

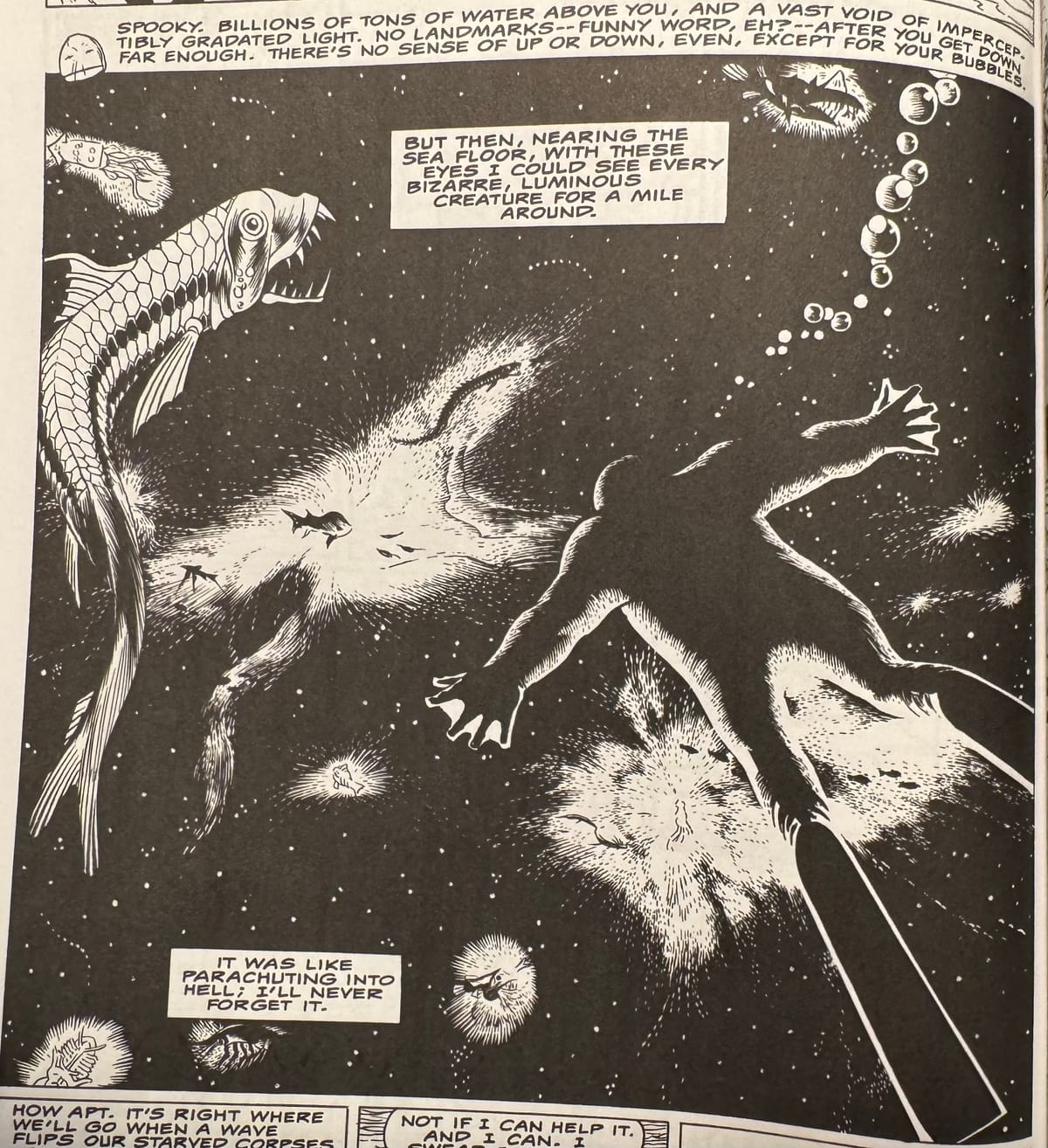

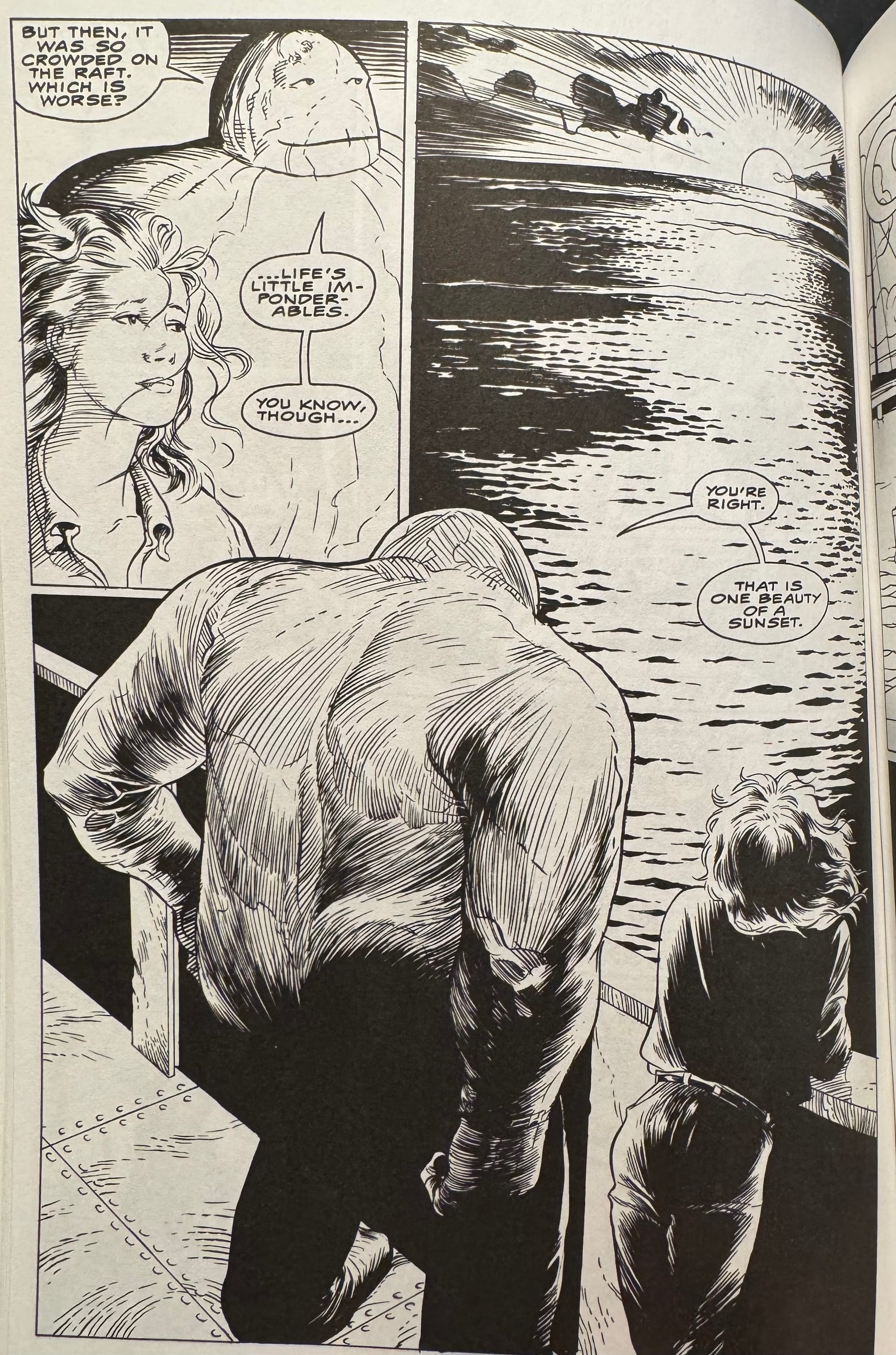

The stories in this collection are largely focused on the idea of a man navigating a new life. Whether it’s Concrete’s daring attempt to swim across an ocean or his struggles with his alien body, Chadwick explores the journey of a man embracing these changes. It’s a very human story, the type of story that seems like a natural extension of the comics of the time yet still in very short supply. In both his writing and his art, he has this natural voice where the story is about a man discovering that he has these incredible opportunities so he takes them.

Sometimes, you can forget about Chadwick’s body-swapping situation, and then Chadwick hits you on the head with it, making you confront it just like Concrete has to. This is a man who would prefer to do what he wants to without much fanfare; he just wants to live his life while taking advantage of the opportunities that come his way. He doesn’t really want the body but as long as he has it, may as well do with it what he can. And then you realize that it is the body that’s giving him these opportunities, taking him on these adventures. He gets the life he wants because of something as crazy as an alien encounter.

So Chadwick has to walk this line between that fantastic element, the superhero-ness of it all, and the desire for both adventure and privacy. It fits nicely into an underserved niche of the time, somewhere between the aforementioned Watchmen and Love And Rockets, offering a little bit of something for everyone. It’s got one foot firmly in genre and the other in slice-of-life stories in ways that not much before or since has. The stories in Concrete: Depth establish this equilibrium between those poles that Chadwick will adhere to in his future stories. Sometimes the stories will tilt one way or another but it always comes back to this middle ground that allows it to live in both worlds.

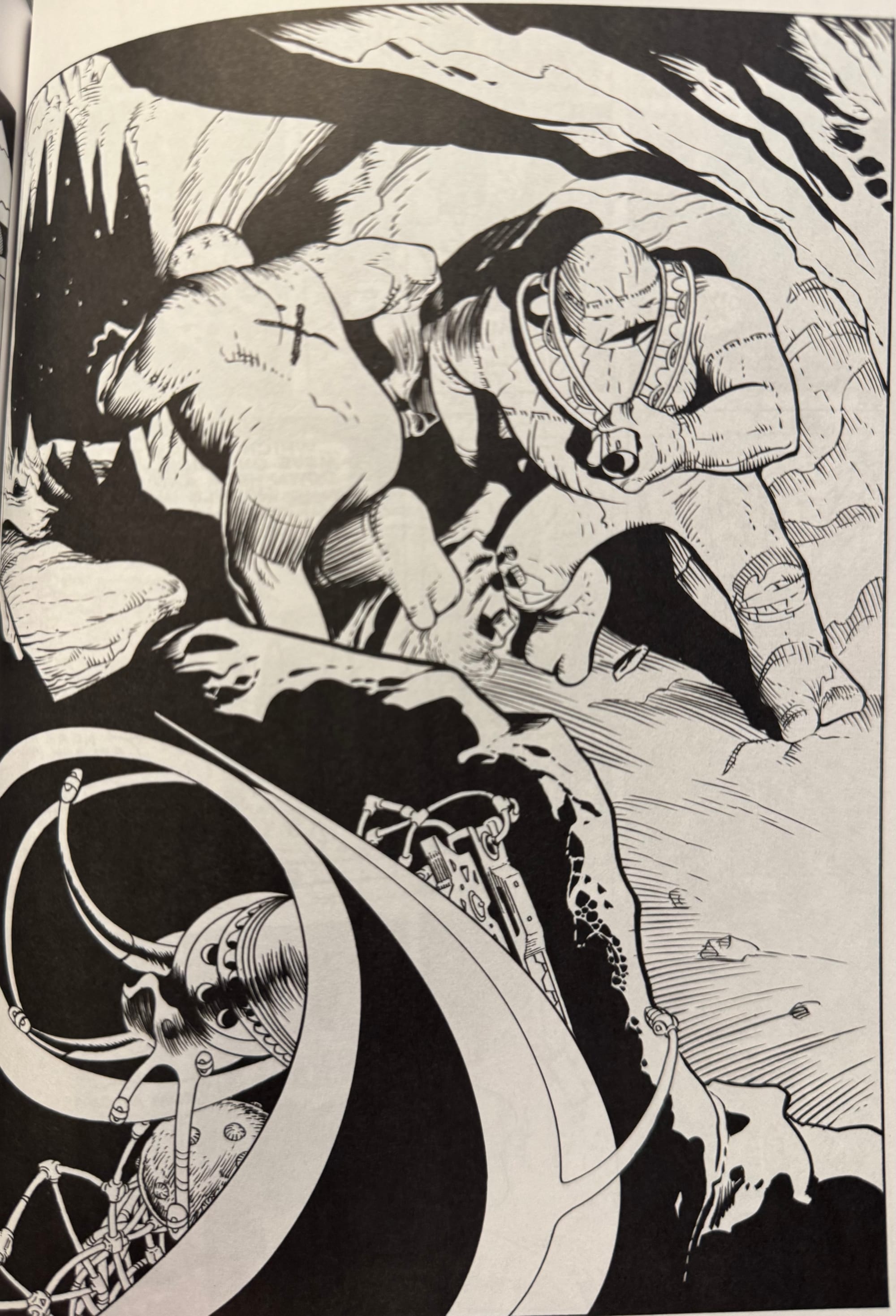

In one of the stories, Concrete recalls the summer when he was 15 years old. He went cave exploring with some friends. It’s a story about young Ron Lithgow (when he had just a normal 15-year-old body and not the incredible one) facing his fears and trying something that he wouldn’t normally do. “Orange Glow” shows us a glimpse of the man that Ron would become. He learned to push himself a bit out of his comfort zone and attempt new things. But it’s also the story of one of the boys he was with getting lost in the caves and never being found. Without calling attention to itself, Chadwick sets this story (one of the later created stories in this collection) up as a mirror to Concrete’s origin from earlier in this collection where Lithgow and a friend explored a cave while on a camping trip and were abducted by the aliens, both Lithgow and his friend get body swapped. Only Concrete escaped, but he never saw his friend again.

The alien origin story is wild and imaginative; it’s good but leans so far in the direction of superheroes. It’s an origin story worthy of anything that Stan Lee or Roy Thomas ever wrote. So it stands out from most of Chadwick’s other storytelling here because it is so fantastic and external to Ron; it’s dealing with a change in his body. “Orange Glow,” the story about a summer years ago, is so similar but also the opposite of the origin story. It has an internal focus to it where the origin is all about the world changing. “Orange Glow” is about Ron changing internally as he experienced those original caves and the tragedy in them. In both caves, Ron lost something and those losses stay with him. But “Orange Glow” is a much more personal story, it speaks to something more spiritual and primal in Concrete’s existence. That makes “Orange Glow” one of the stronger stories here because it is about an internal struggle as opposed to the external challenges most of these early stories are about.

As an introduction to Concrete, Concrete: Depth doesn’t take us into a new world but gives us a different perspective on our world. Paul Chadwick’s stories are just these humane tales. And sure, there are differences when you’re a giant being made of rock but by telling those stories, Chadwick focuses on the humanity of Ron Lithgow, helping us see the man behind those alien eyes.

Comments ()