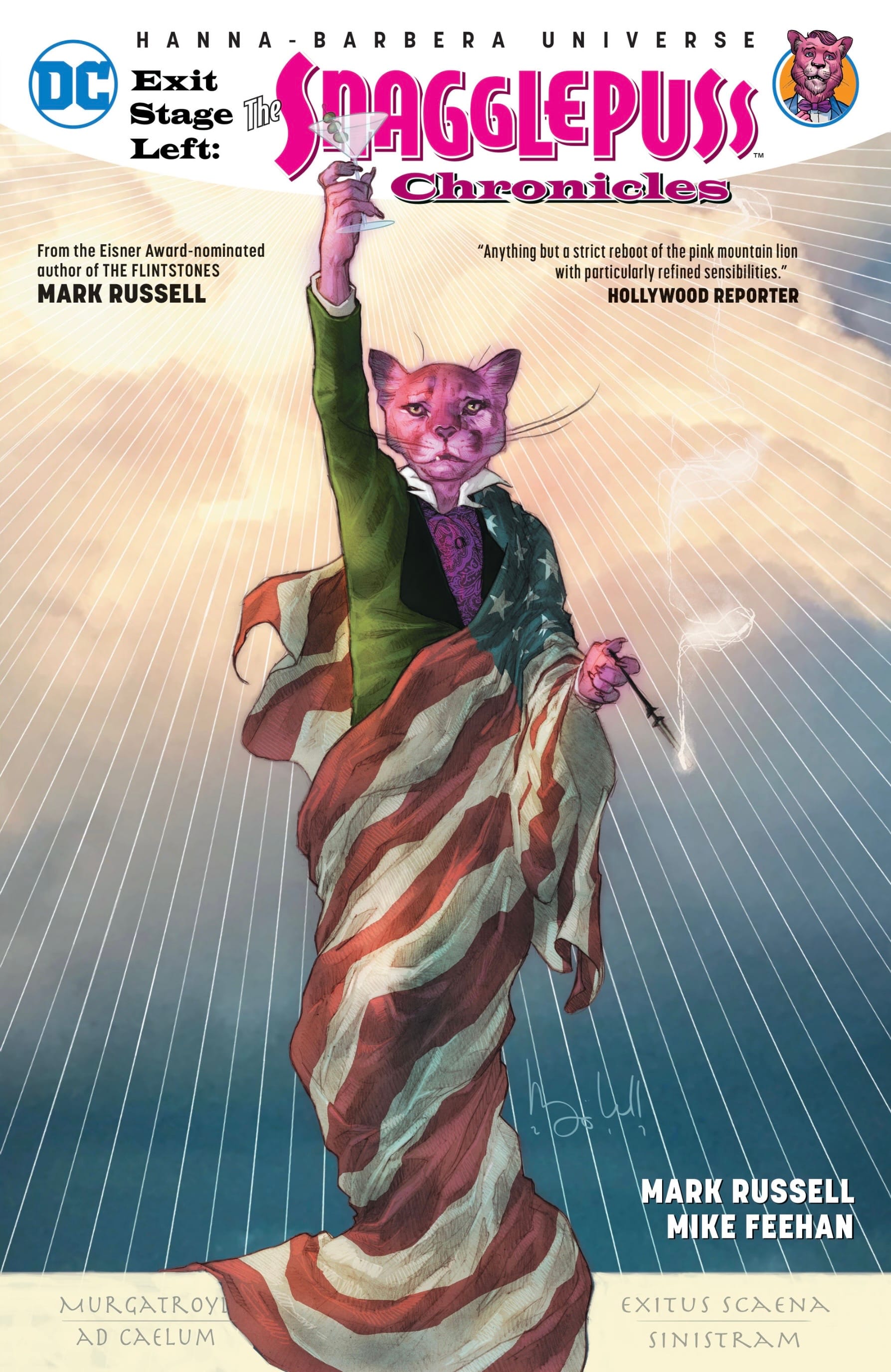

“Change Your Heart…”— Lessons from Mark Russell and Mike Feehan’s Exit Stage Left: The Snagglepuss Chronicles

Mark Russell and Mike Feehan’s comic is a reminder and a call to arms.

You probably wouldn’t expect to find a story about the queer experience in the 1950s in a comic book that’s based on a cartoon character but that’s exactly what Mark Russell and Mike Feehan did in 2018’s Exit Stage Left: The Snagglepuss Chronicles. Oddly, they begin in 1953, six years before the character’s actual debut on “The Quick Draw McGraw Show,” and they work that into the story, exploring the life of this cartoon character before he became a television star. So it’s the story about how he became a TV celebrity but it’s much more than that— it’s the story of the 1950s, about the repression, fear, and power of the time. It’s the story of a government out of control, seeing enemies everywhere (in this case, Communists,) and out to stamp it down before they gets a hold on our good, American culture. And while the book doesn’t come out and say it, it’s heavily implied that good culture is “Leave It to Beaver” and “Ozzie and Harriet.” In other words, it’s patriotic, straight, and white. And if you don’t fall into one of those categories, then you must be a godless Communist. It all was as black-and-white as the television of the times.

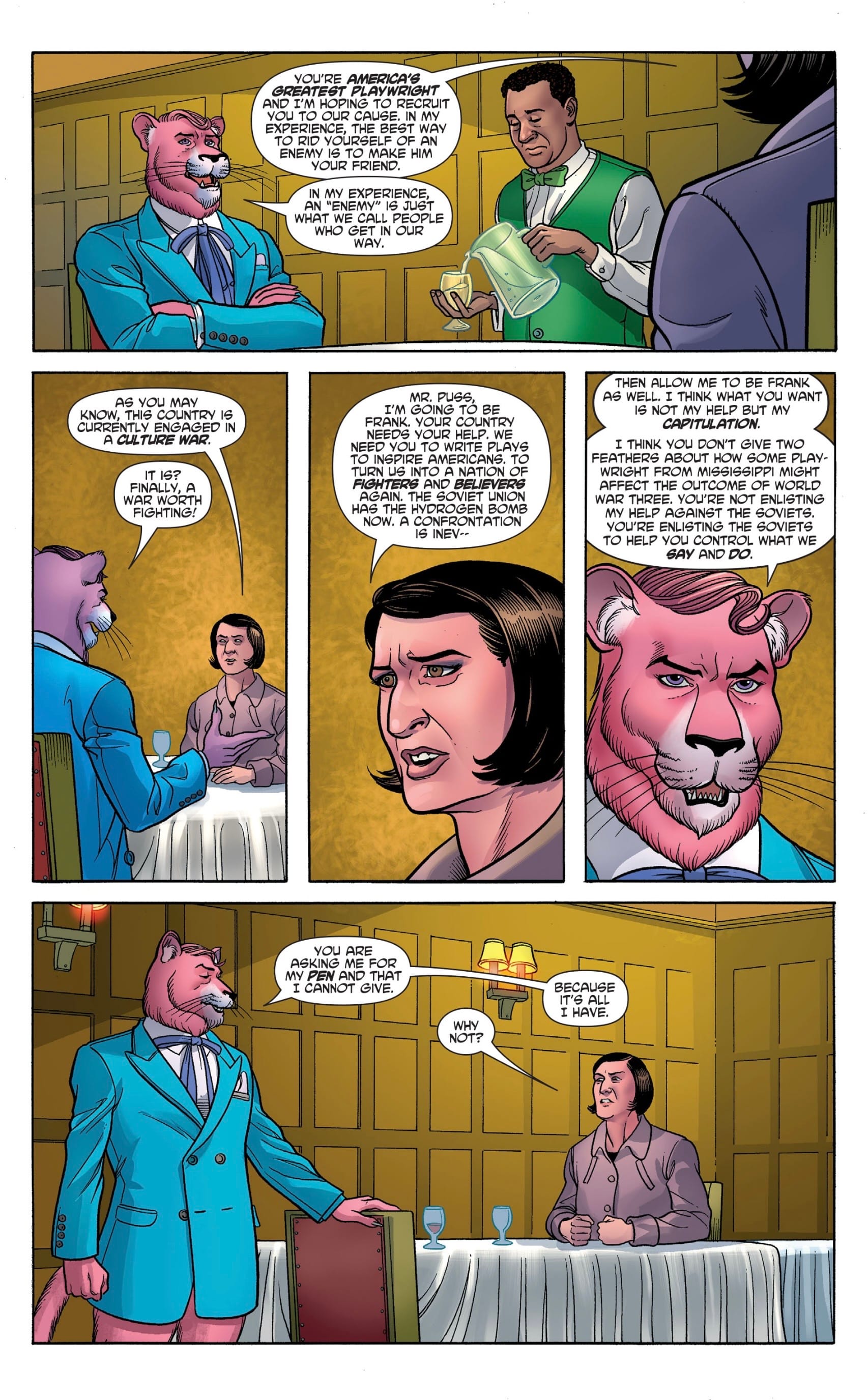

Snagglepuss is a man (mountain lion?) that has it all— he’s a famous playwright, married to a wonderful woman, and can get into all of the best restaurants. He’s respected so when he’s called before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) to testify and to give names of Communist sympathizers, he casually disarms his inquisitors. When directly asked, “Have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” Snagglepuss deftly answers “Lord of Heaven, no! I never even go to parties anymore.” He walks out of that first committee hearing unscathed and his head held high. And that’s an attitude he carries through much of this comic; he deflects suspicion and attacks in ways that few can. Yet even as he deflects, he’s hiding something from the committee and the world. The marriage is a shield from the truth; he’s a gay man in a society that’s scared of homosexuality and condemns it.

Exploring the ways that we play roles to protect ourselves, nearly every person in this story is trying to be something that they’re not. At the most basic level, you have the actors in Snagglepuss’s plays, human actors wearing costumed animal ears and noses. They’re one aspect of Snagglepuss’s voice; there’s an equality present on the stage that’s seen nowhere else in this story. The theater seems to be the safest place in this book, where all of these different people come together without prejudice. Russell and Feehan show the work that’s involved but they also use the stage to show the purity of art.

Set in the repressive 1950s, Snagglepuss has to hide that he’s queer. It’s portrayed as one of those secrets that the people closest to Snagglepuss know but if you’re not part of his circle, you think he’s “100% American.” He’s a celebrity; he’s the great American playwright (think Tennessee Williams.) Snagglepuss is really good at hiding in plain sight. He carries himself with the confidence of who he is and what his actions are, which another character, Huckleberry Hound, lacks. Huckleberry Hound, Snagglepuss’s old and dear friend, isn’t as good at keeping his secrets. So like his actors, Snagglepuss has to take on many roles just as he makes those in his life take on roles. As a gay man (let’s just call him a man as it’s easier than saying “gay mountain lion”,) we see Snagglepuss put on a straight persona for the public to see. He’s married so he can’t be gay, right? Russell and Feehan are trying to show this 1950s society that’s one thing on the surface and then something else underneath it.

Snagglepuss has the carefree attitude of a Southern Dandy. He faces off against the House Un-American Activity Committee, armed only with his bon mots, and walks out the first time unscathed. He’s a New York playwright who has wealth, fame, a beautiful wife, and can get a last-minute reservation at all the right restaurants. He’s the man (or tiger) of the moment. Snagglepuss has to hide that he’s queer. It’s portrayed as one of those secrets that the people closest to Snagglepuss know but if you’re not part of his circle, you think he’s “100% American.” He’s the great American playwright (think Tennessee Williams.) And Snagglepuss is really good at hiding in plain sight.

And yet for all of the ways he tries to protect himself, he has to expose himself and give in to his fears to try to inspire change. There’s something here as Snagglepuss has to be a sacrifice in ways that no other character in this book can be. He stands up to the HUAC and ends up losing everything because of it. He speaks truth to the committee and the American people. “There is no greater tragedy in life than to die a stranger to yourself. Conformity and shame destroy people. And a culture that doesn’t fight back is as useful as an old calendar.”

Russell and Feehan’s comic is a reminder and a call to arms. Back in 2017 and 2018 when this was first coming out, in the early years of the first Trump presidency and MAGA and all of that, there’s definitely a way to read this as “those who don’t remember the past are doomed to repeat it.” But now that we’re only a year into the second Trump regime, it feels like we’ve moved beyond just remembering the past and now have to do something about it— to take up the call of Snagglepuss and to live the lives we’re supposed to, to stop being strangers to ourselves.

So Exit Strange Left: The Snagglepuss Chronicles isn’t a call to revolution but a call for change. And as David Lunch once put it, “Change your hearts or die.” And yes, it’s strange to get this lesson from a pantsless human-like pink mountain lion (or whatever Snagglepuss is) but by removing those human physical qualities from Snagglepuss, Mark Russell and Mike Feehan end up making the message so much more universal. It’s not a story about protecting something that’s othered; it’s a story about protecting ourselves and our loved ones from fear, anger, and repression.