The Form Is the Story in Kevin Huizenga's Fielder #3

Huizenga’s playful pages lead to the truth of his cartooning.

There’s a thrill in finding a comic that can’t be adapted into a TV show or a movie. That means that comic does something so unique with story, art, and form that it can only be told on the page with words and pictures. Those are rare comics— always have been, always will be. It’s the way the system works, especially during the last twenty years or so. Whether it’s a stab at IP or using comics to launch into other media, too many comics just read like a pitch document. They’re designed to get into a few people’s hands but constructed to sell their soul to Hollywood. That’s not Kevin Huizenga’s Fielder #3. This is one of those thrilling comics that is exciting because it is a comic book and it could not ever be anything but a comic book. The stories that Huizenga writes and draws here are comics, could only be comics, and are a celebration of comics.

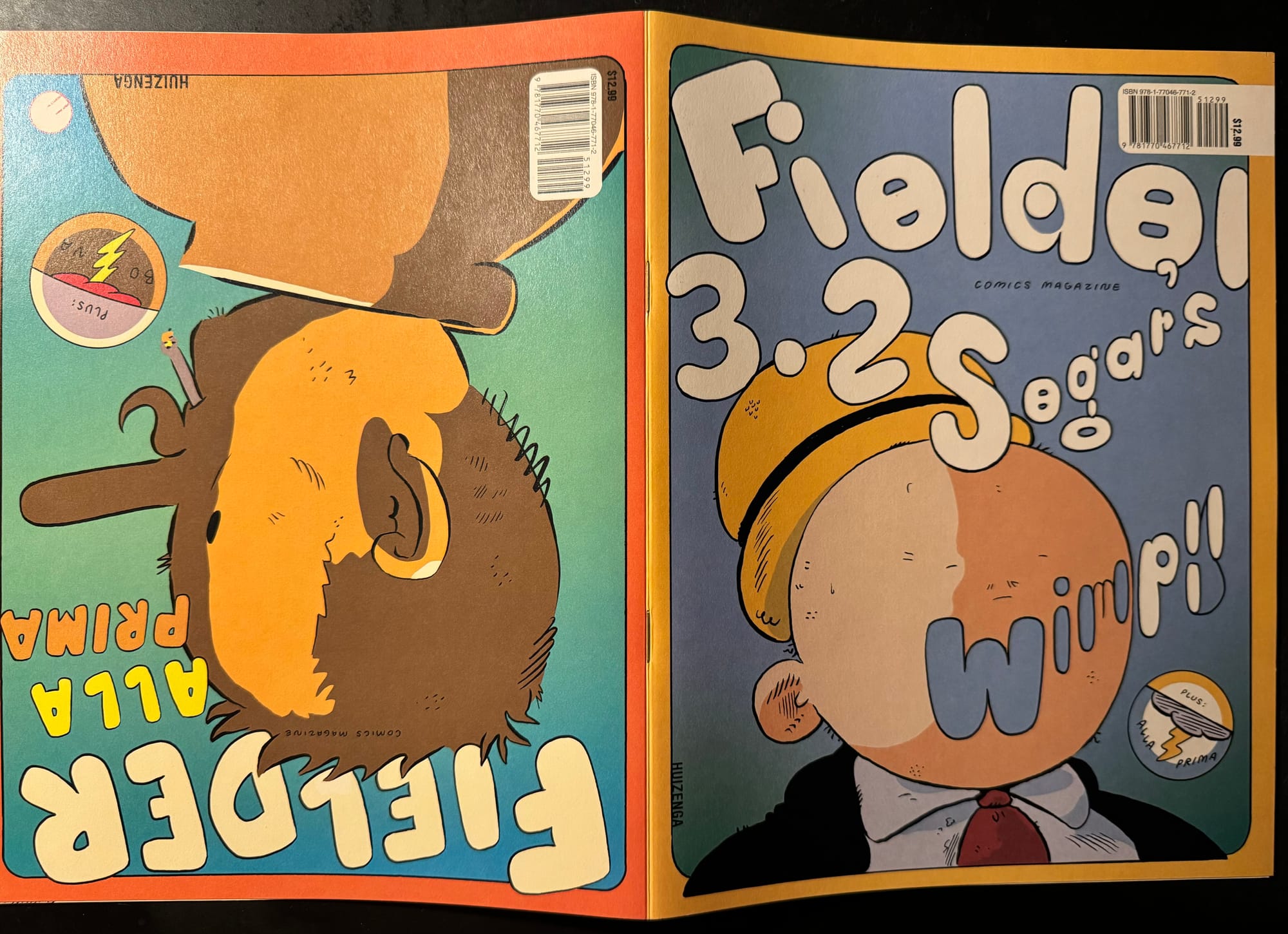

As a flip book, one of the first things you’ve got to realize is that you can’t trust Huizenga. Flip books themselves are always suspect to begin with; there’s a clear beginning but is there really an end to them? Or do you get trapped in this cycle of just constantly flipping the book over and over again, caught in an infinite loop? More than that, there’s a question of how much we can trust Huizenga’s storytelling. This is more than an unreliable narrator- it’s an unreliable creator. As a flipbook, turn to either cover (there is not front cover and no back cover) and you’ll be at the beginning. And at either end of the flip book and you get a story about Glenn Ganges.

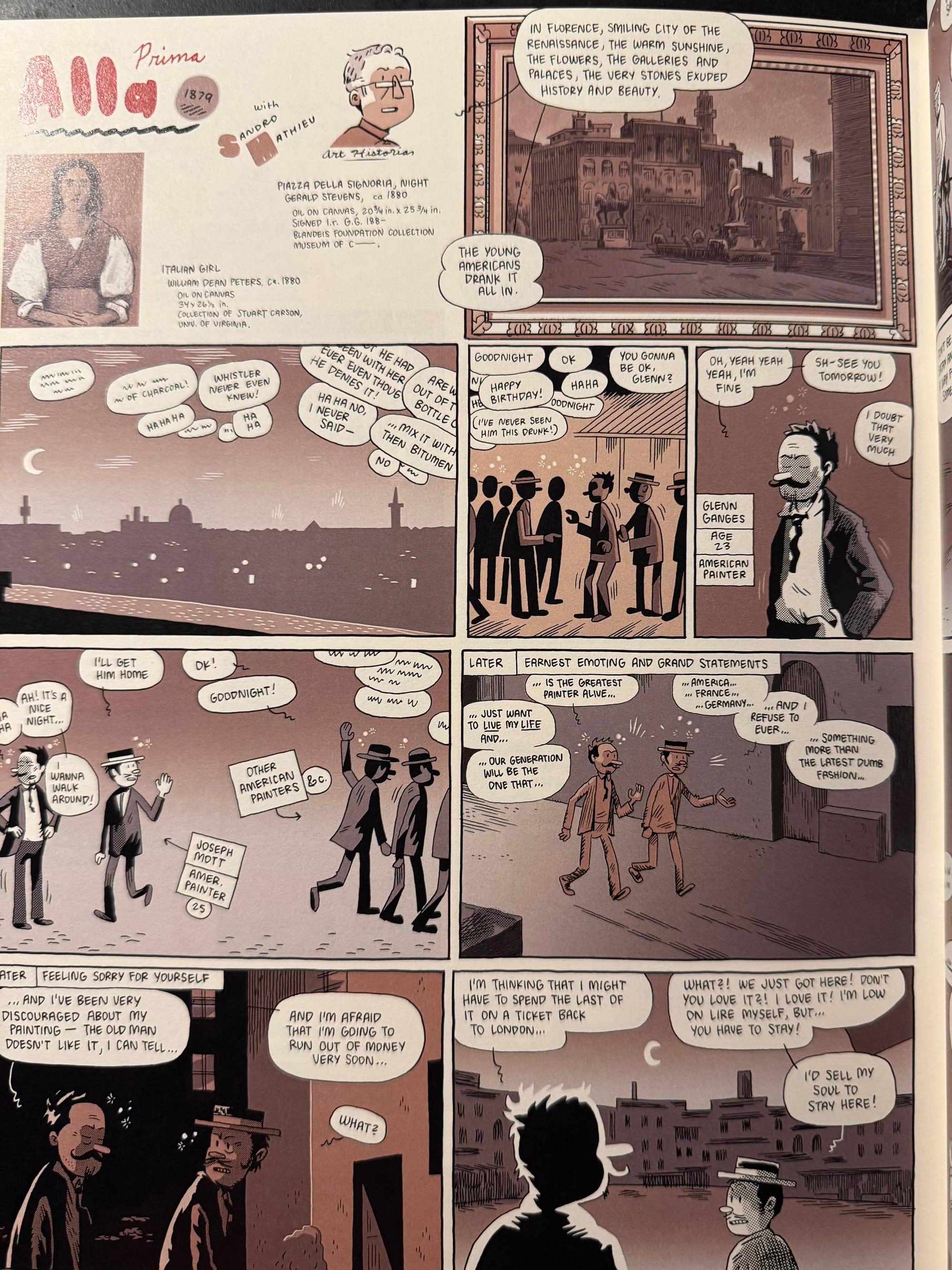

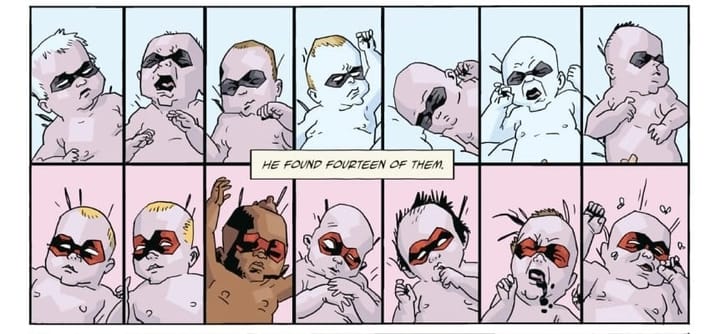

Pages from Alla Prima and You And Me

Now if you’ve read much Huizenga before, you’ll recognize Ganges as a veiled stand-in for Huizenga in his semi-autobiographical comics like Curses or Ganges. Glenn is to Huizenga what Alec is to Eddie Campbell (hopefully you’ve read The Years Have Pants or any other Campbell to get that reference to Campbell’s autobiography comics that began as a story about a man named Alec but clearly became autobio as Campbell eventually changed Alec’s name to “Eddie,”) but maybe just a little bit less so. Maybe Ganges is going in the opposite direction from Alec; where Alec eventually became Eddie in the comics, Ganges seems to be moving farther and farther way from being a direct avatar for Huizenga in his comics.

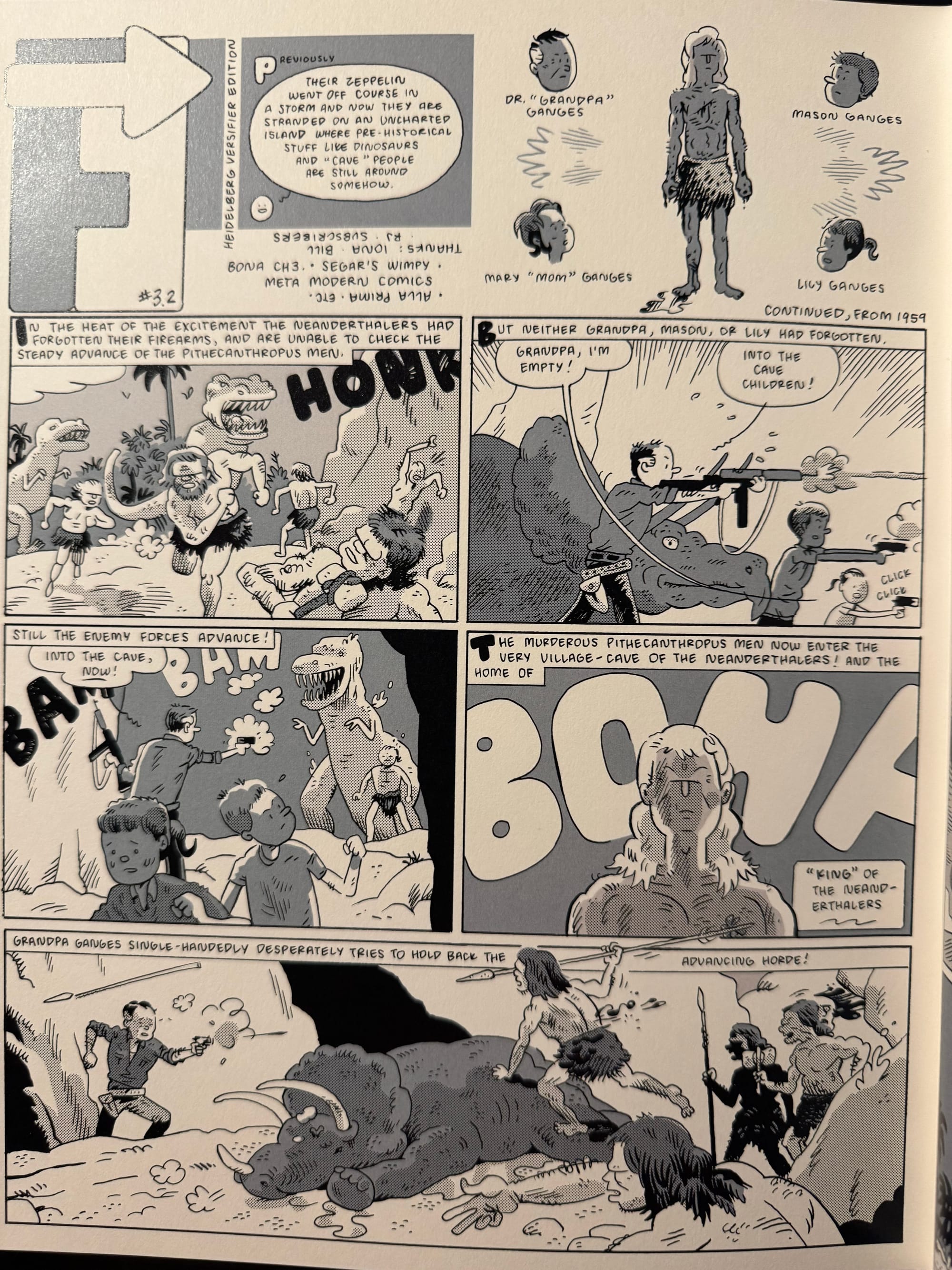

From one of the covers, the comic opens with a story about a 19th-century American-in-Paris painter named Glenn Ganges, trying to learn his craft at the foot of a master. This is loosely based on a true story. Start on the flip sIide and you’ll read a story about “Grandpa” Ganges, a 1959 modern man trapped in a prehistoric past. Both stories are presented as authentic comics but one is a piece of historical fiction while the other is a riff on Sam Glanzman-drawn adventure comics from the 1960s. Both stories are Huizenga inserting his character Glenn Ganges into these stories, inserting himself into these stories that he knows about but wasn’t actually a part of.

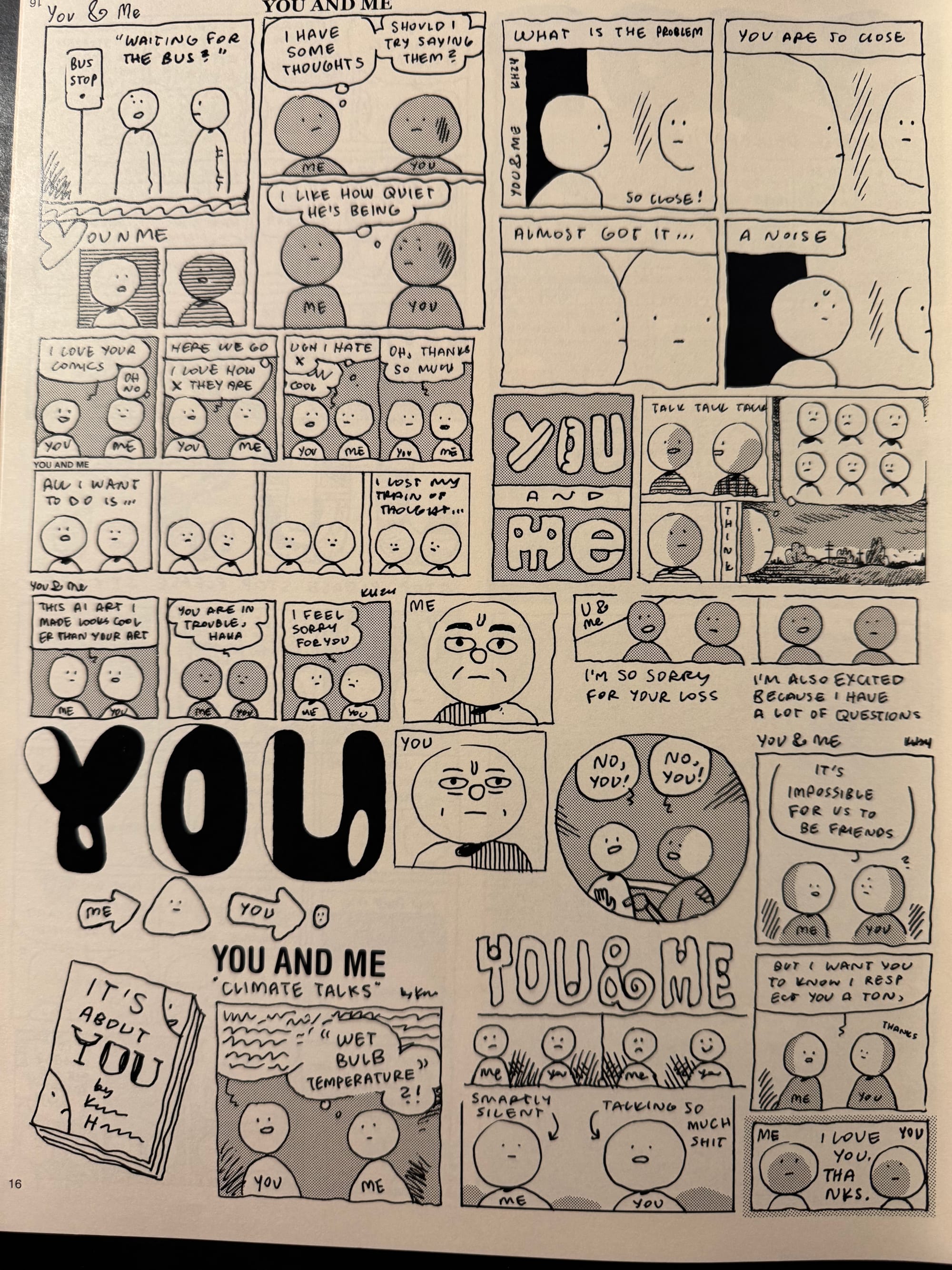

None of these strips have the same narrative structure. In each one, Huizenga finds a form and a rhythm unique to the story. It could be the more traditional panel structure of “Bona” or the “You And Me” strips that feel like Huizenga just started noodling in his notebooks and before you knew it, he had pages and pages of these strips. He modifies the language he uses for each story, all the way down to the syntax of the page. Each of these stories requires their own identity and Huizenga is excellent at finding different ways to tell his stories. This is where we can find the truth in his comics.

Under Huizenga’s pen, the comic page is a living, breathing canvas. These pages possess their agency and their reason for being. That agency is unique to each story. For the stories that he’s telling, Huizenga finds ways to fit the form of the story to its function. It’s the formalist in him. We’ve seen him experiment with this many times before— his mini fight comics are as close as you can get to abstraction while still having a narrative. But they’re as real and true as his autobiography stories which are far more linear and traditional. He’s always played with form as another tool that he could use. And so much of his comics are finding the right tool for the job.

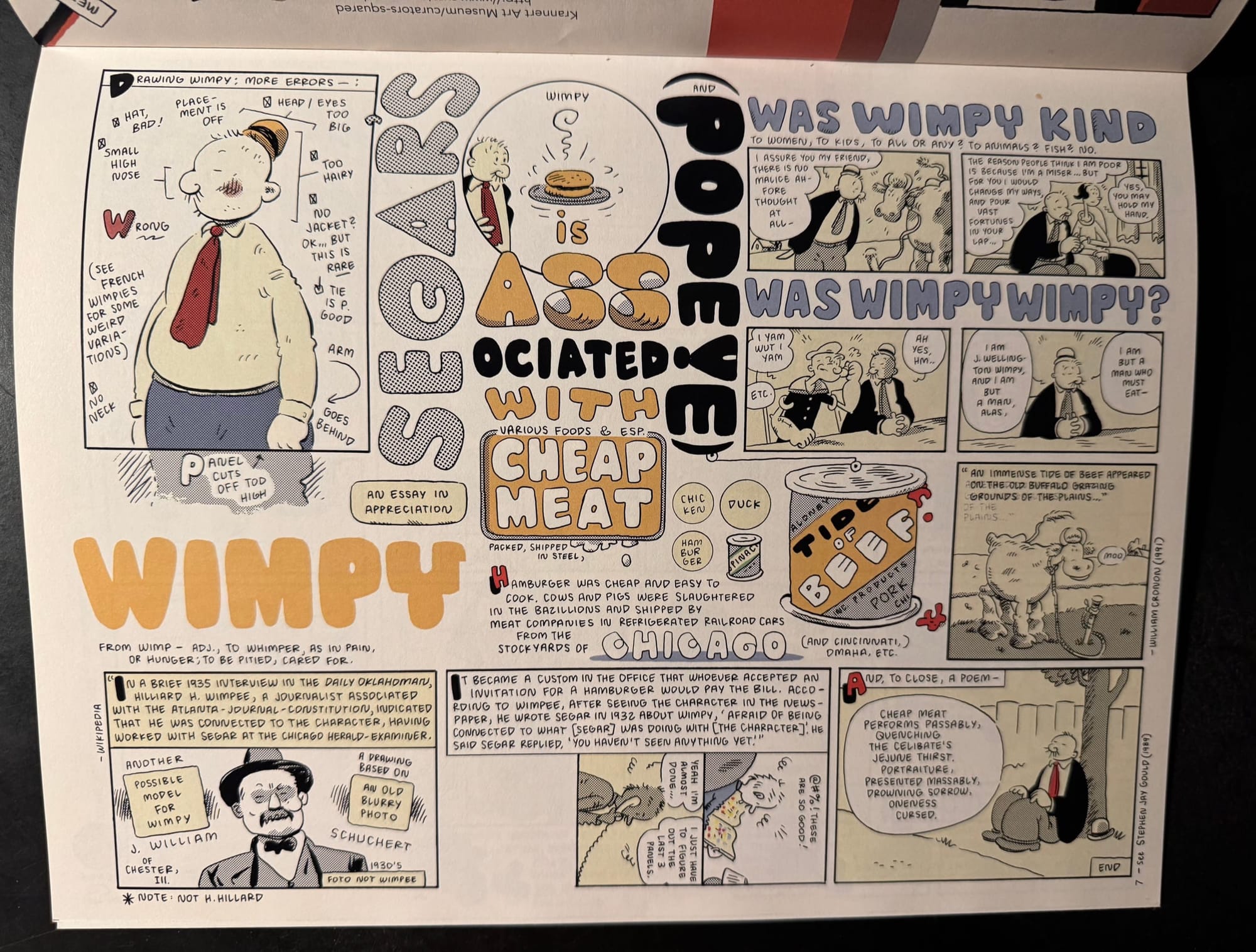

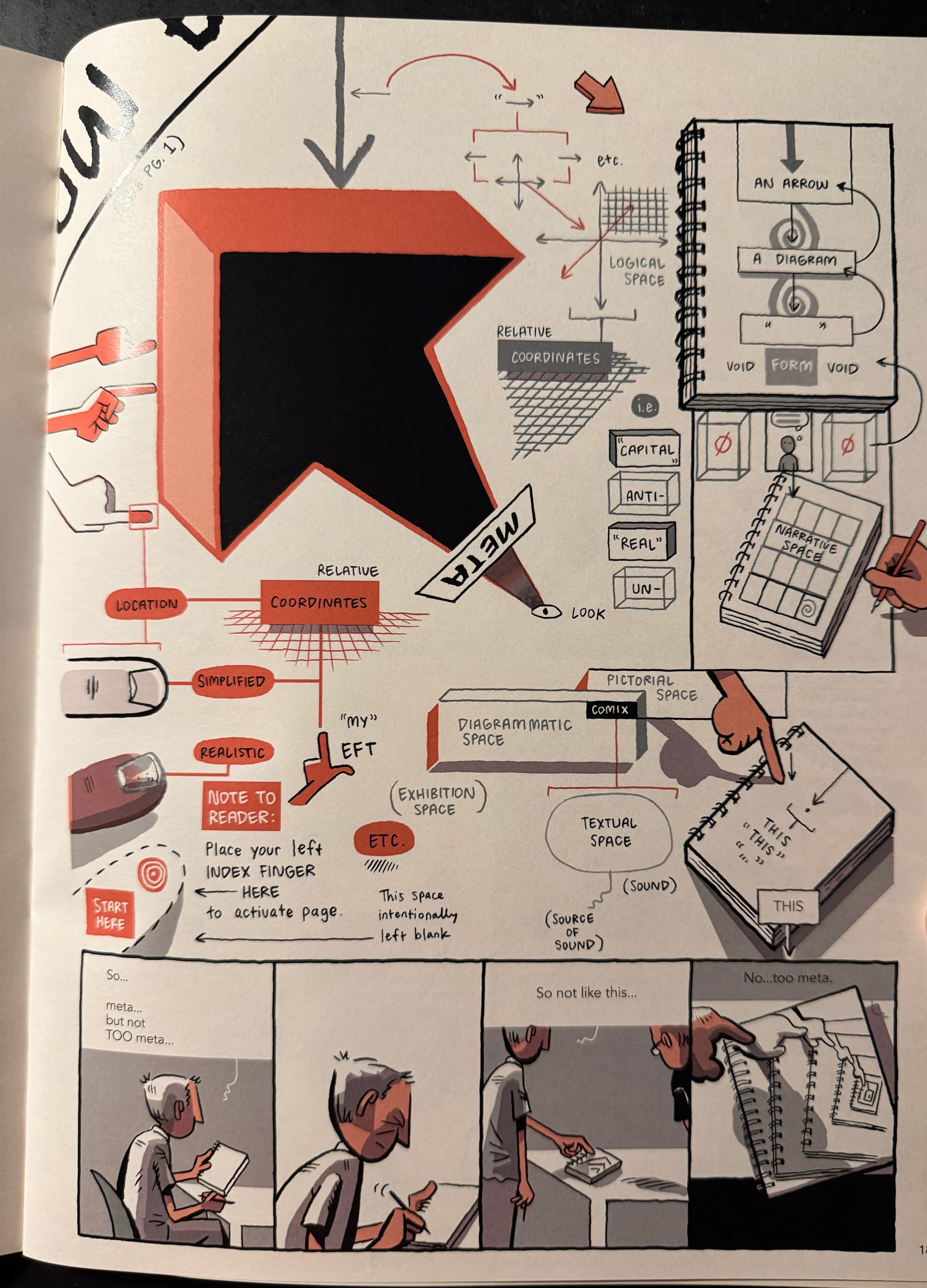

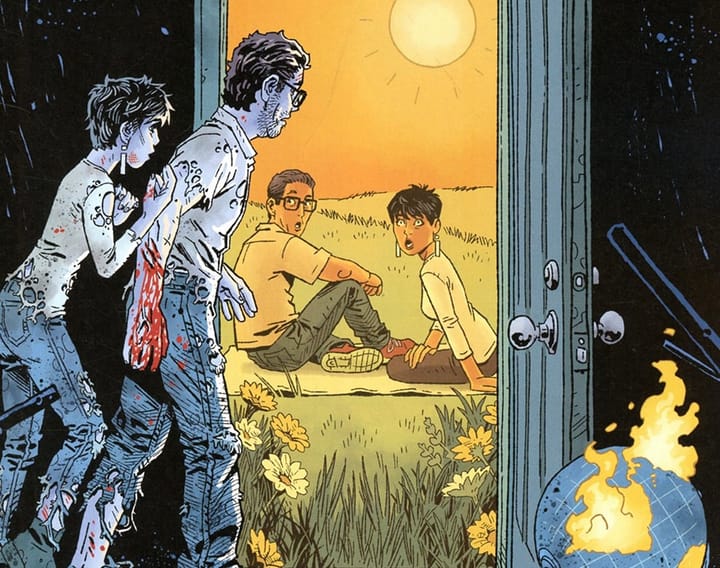

Pages from Meta Modern and Bona Chapter 3

When he wants to do an appreciation piece about E.C. Segar’s character Wimpy, he rotates the pages to a landscape orientation, cramming as much as he can into four pages. It’s like he has so much to say about Segar and Wimpy and he doesn’t think he’s ever going to get a chance to again so he’s got to get it all out. Even in these pages, he subdivides the pages into four or more subsegments, each one with its specific focus. So here, the function is to get as much of his thoughts out on the page as possible. Those four pages are followed by a piece about a collaboration with University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign art professor Conrad Bakker to create a piece for an exhibition catalog about furniture designers Charles and Ray Eames. As described in the piece, this is a “comic/visual essay on the Eames studio…”. For as free-flowing as the Wimpy piece is, this piece is a flowchart of storytelling where the form is the function.

Throughout Fielder #3, Huizenga practices a purity of cartooning. In this drawing, there’s an honesty implicit in each image that captures something of the human experience uniquely and confidently. Even if a few of the stories challenge the boundaries of “truth” just a tad bit, it all becomes true as Huizenga has found this blend of storytelling through story and through drawing that finds its truth through that mixing. Huizenga may not be a reliable, truthful storyteller but is that anything to hold against him when he’s telling these rich, complex, and heartfelt stories? Within these pages, you have a fairly traditional action strip, an appreciation of an old comic strip character, an almost abstract rumination on a design house, a quasi-historical tale of a 19th-century expat artist, and a concentrated collage of strips. The connective tissue of all of this is Huizenga’s playfulness with the structures of these stories. In the end, the only rule to follow when reading these comics is that there is no truth or untruth to these stories because it’s only the comics that matter.

Comments ()