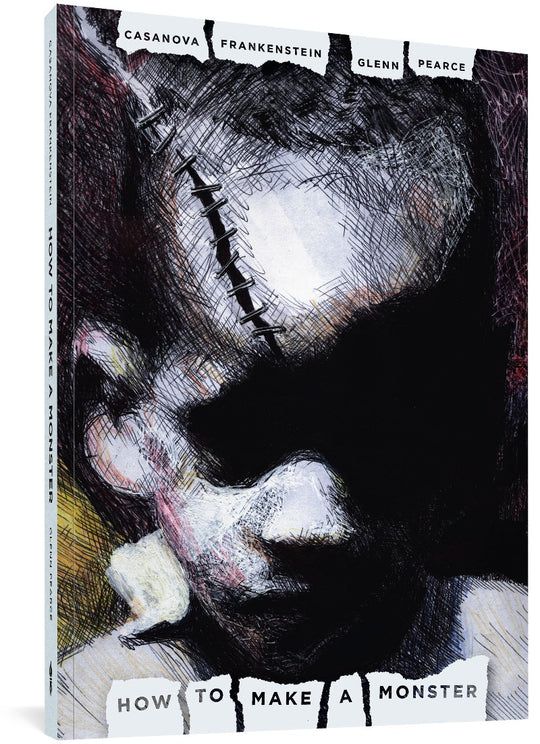

Can a kid just be a kid? Thoughts on Casanova Frankenstein and Glenn Pearce's How To Make A Monster

Casanova Frankenstein and Glenn Pearce map out the childhood trauma that forges the person we become, allowing us to accept the monster in us.

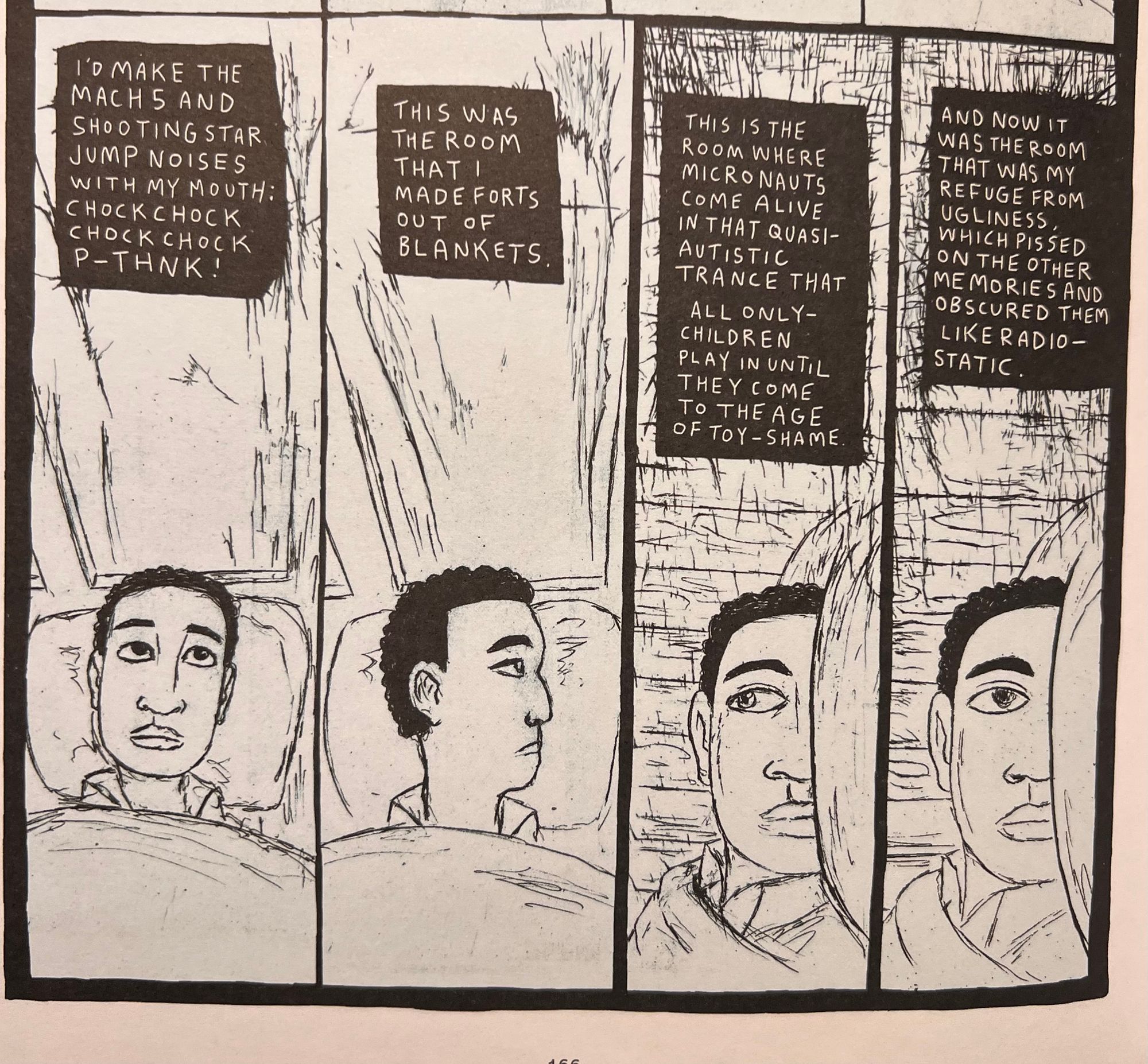

The way Casanova Frankenstein tells us about what it was like to be an 8th grader in a south-side Chicago, religious school is almost instantly recognizable to me. I grew up about 15 miles away from where he did. I wasn’t yet in a private religious school (that would come about a year later for me, in high school) but his depiction of growing up middle class in the 1980s feels so familiar: I had so many of the same pop culture interests and experiences as he did. There’s this one portion of the book where he talks about waking up early in the morning, before anything good is on TV, and watching the farm report on a local TV station before the good stuff came on. “The farm report was still on. Maybe five minutes until the Ray Raynor show. I didn’t get the farm report. All that talk of ‘pork bellies’ going for so and so dollars. It was confusing. Surely there were no farms in Chicago,” was a strangely nostalgic thing to me, bringing back memories of those same mornings, watching those same farm reports, and trying to figure out where there was even a farm around us. I haven’t thought about those farm reports in years, probably decades. But suddenly I’m right back there, stuck with a limited amount of channels to watch on the TV before the ubiquity of cable TV, and just perplexed by this report that seemed so important to adults. How To Make A Monster was leading me to that moment and then BOOM! I was entirely in the book, identifying with Frankenstein and his childhood.

The big difference is that he grew up on the mostly black south side of the city, but firmly in Chicago, while I was just a kid from the white suburbs– so close but worlds apart. Glenn Pearce’s drawings of Frankenstein’s memories turn this childhood connection between us into an absolute horror story, almost retroactively rewriting some of my own memories of childhood to frame them similarly to Casanova’s. Casanova Frankenstein and Glenn Pearce depict childhood as a series of emotional beatings that wear down on a thirteen-year-old, but ultimately in an oddly optimistic and mystifying way as it prepares that kid for what’s next in his life, the monster that’s waiting in all of us during high school and beyond.

“…Casanova’s memories are those of an innocent young man living in a godless world.”

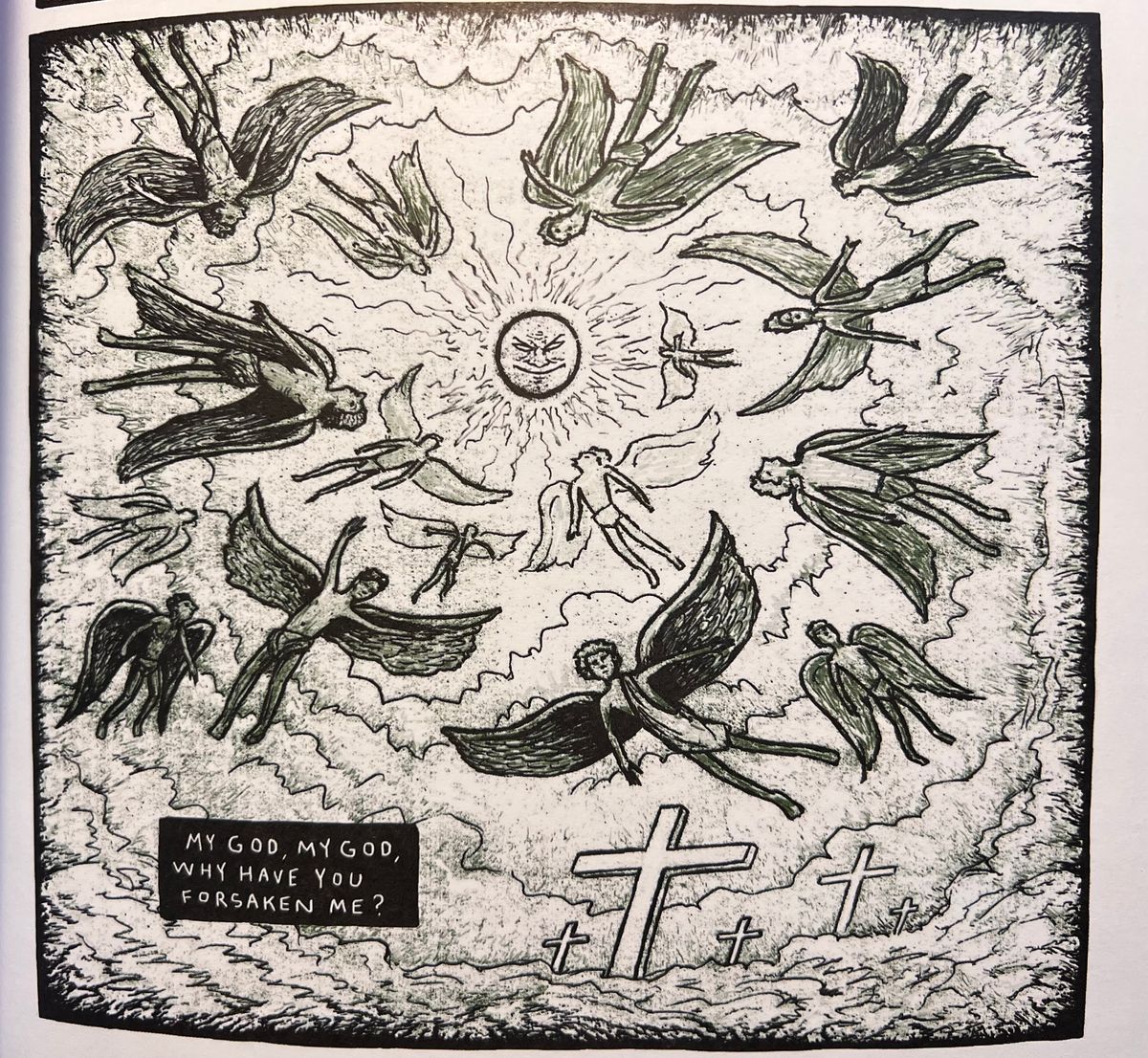

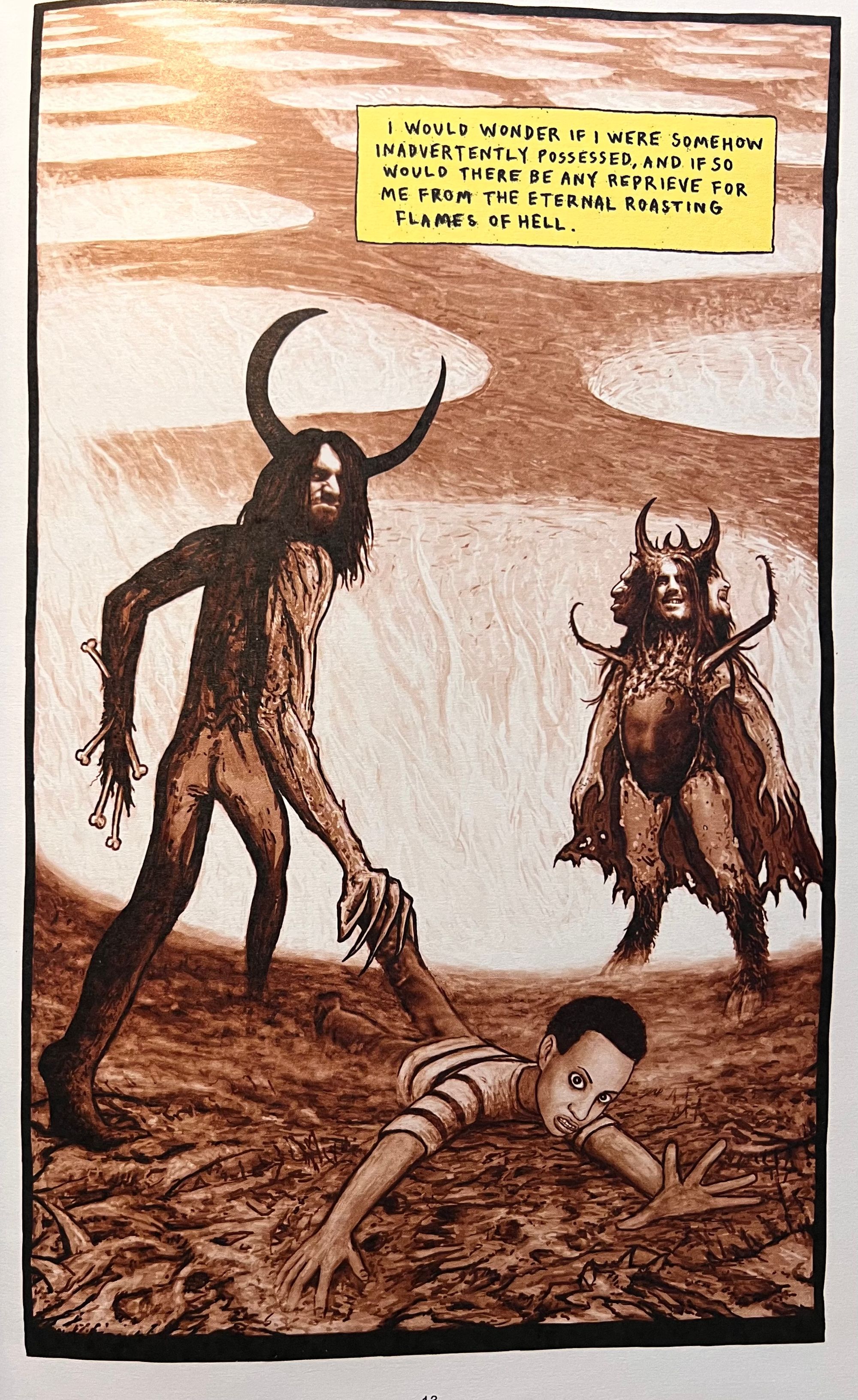

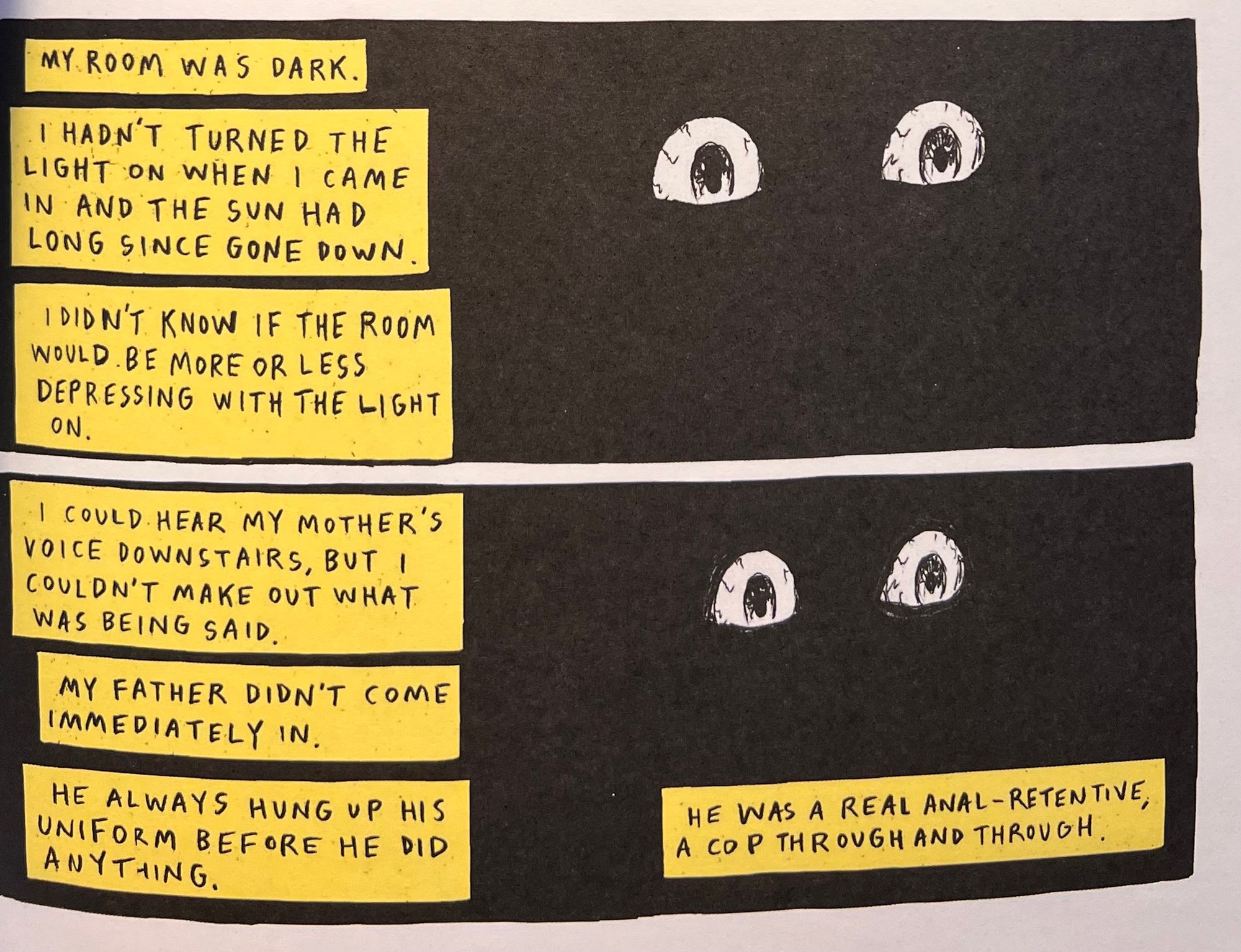

“The 1980/1981 school year started with a dismantling of childhood and got steadily worse,” an older Frankenstein tells us on the first page, leather clad and sitting at a bar, an ashtray full of cigarette butts next to him. A self-described loner up until 8th grade, he describes the previous years of his childhood as “fairly normal” until puberty, hormones, and all of that stuff hit everyone in his school and everything changed. This chronicle of eighth grade shows a kid who wanted to stay a kid even though the world around him was changing and becoming even more threatening. He had lived with a certain amount of fear up to that point; his cop father had instilled that in him but that fear had centered on his father, not on the rest of the world around him. Telling this story from the remembered perspective of childhood, the south side of Chicago becomes hell on earth. Maybe it is a holdover of concepts from his religious schooling but Casanova’s memories are those of an innocent young man living in a godless world. So if there’s no God, what else could there be to fill his soul?

Pearce’s artwork turns Chicago into an urban Hieronymus Bosch hellscape populated by school-age demons and torturous adults. Recreating Frankenstein’s childhood, Pearce concentrates on creating horrific images from a child’s point of view. It’s almost like he’s reshaping that happy-go-lucky movie A Christmas Story– you know the one with Ralphy and his father, Christmas, triple dog dares, the furnace, and its way of recreating memories with a tinge of rosiness– without the comfortable haze of nostalgia. Frankenstein and Pearce are practicing a similar kind of looking back at pivotal events from childhood as that Christmas movie did. Where that movie was wrapped in the warmth of the holidays and memories, this book remembers a similar age for the main character with terror and the dread of surviving the horrors that wait around the school hall corner.

Through his vivid depictions of events colored by the fear that Frankenstein remembers as much, if not more than the happening itself, Pearce’s pages are just one horrific moment after another, showing the hell of 8th grade, trapped between being a kid and a teenager. Whether it’s an encounter with a disapproving secretary in the principal’s office or navigating the way home to avoid Frankenstein’s teenage tormentors, Pearce makes it hard not to confront these horrors of childhood without feeling as if they are your own. He takes this incredibly personal story and makes it even more relatable to the reader, putting you in Frankenstein’s shoes and making you face his fears.

“It’s off-putting to read this journey, to get to the moment of realization, and then a few minutes later, you hit the last page of the book and it’s done.”

All of this makes the book sound like it’s a horror book, which it is, but it’s something more than that. Frankenstein is doing more than just telling us about his crappy 8th grade in a religious school where God seemingly didn’t exist, or at least, where he didn’t care about this small, scared kid. And even when he plays hooky to escape his school, Frankenstein finds a largely uncaring, unforgiving, and unrelenting city that doesn’t let a little kid be a kid. Three-quarters of the book shows us this world that is actively telling Frankenstein that he doesn’t matter and, worse yet, it may be better if he wasn’t there (not in a suicidal way but in an existential one.) As he’s getting older, he’s witnessing what becoming a teenager supposedly means in his classmates (supposedly being an “adult” means bullying those you can) but he also sees his father reflected in nearly every adult, a cop with a short temper who parented through fear instead of love.

All of this- the fear, the uncertainty, the desperation, and the need- lead up to the making of the monster and that moment when Frankenstein discovers his salvation. It’s a revelation for him, just as it should be for the reader so we’ll avoid spoilers here. It’s off-putting to read this journey, to get to the moment of realization, and then a few minutes later, you hit the last page of the book and it’s done. There’s so much build-up, and then a revelatory breakthrough that would normally lead to the climax and a resolution. But Frankenstein and Pearce get to the emotional breakthrough and it is clearly a life-changing event for Frankenstein. And then…

The monster is something personal. In ways, we’ve seen the monster throughout the book, some obvious in hindsight and others hidden. Accepting the idea of a transformation into a “monster,” The book makes us see how at some point in childhood we’ve got to accept that we’re part of the world and give into it, becoming one of the demon tormentors. Or we can choose to be a monster, an individual disconnected from the world, finding our own means of expression and existence. Most of us probably fall somewhere in between, sacrificing portions of ourselves to fit neatly into everything else. For Frankenstein, the monster is part of his identity (hence even his name); you can’t get to the monster without understanding the journey that came before it.

The memory of these events help define Casanova Frankenstein. Those events and torments primed him and made him ready for discover and for revelation. Frankenstein and Pearce guide us through this painful story, laying out Frankenstein’s emotional wounds from that time and giving us the opportunity to reflect on our own pains. It’s the opening of wounds for examination and reflection. And it hurts. Frankenstein’s memories in How To Make A Monster are his own but he and Pearce find ways to explore them that creates ties between the creators and their readers. And during those explorations, Frankenstein shows us how all those painful events are still part of who we were then and who we’ve become because of them.

Comments ()