Gaiman and Buckingham write the new gospel of Miracleman in The Silver Age

You’ve got to wonder what Miracleman: The Silver Age would have read like if it had come out in the 1990s instead of the 2020s.

It’s 2024 and maybe we need superhero deconstruction stories now more than ever before. In comics, we experienced deconstructionist stories both in the 1980s and 2000s, in cycles that explored not just what the fantasy of superheroes meant but what our fascination with superheroes meant at those times. In the 1980s, Frank Miller, Alan Moore, Rick Veitch, and their compatriots first started pulling apart superheroes. Looking back at those times, there’s a bit of a feeling of a dog chasing its tail; superhero comics commenting on superhero comics but who else was going to do it? It was “adult,” “dark,” and “cool” when Rorschach killed his enemies during a prison escape or when Batman took on the mutant gang. Watchmen and The Dark Knight Returns are key texts that defined those times and popularized the idea of text commenting on text in comic books. But even before Watchmen, Alan Moore tugged at the superman’s cape beginning in the early 1980s with his Miracleman, the story of a powerful superbeing who had forgotten that he was powerful or a superbeing. (This is two decades before Paul Jenkins and Jae Lee would use that basic idea for Marvel’s The Sentry.)

Flash forward to the 2020s as Neil Gaiman and Mark Buckingham finally return to their continuation of the Miracleman story. Moore and John Totleben wrapped up Moore’s story with Miracleman reshaping the world in his image. He was a new god walking the earth and making it a reflection of himself (for the betterment of humanity he would have argued.) In Gaiman and Buckingham’s first story arc, “The Golden Age” (originally done in 1990/1991,) they explored this brave new world that Moore had left them. Imagine living in a world of superheroes, aliens, and shamans where nothing seemed impossible and the world was so much the better for it. They showed us people living their lives in the world that Miracleman created through multiple points of view; each chapter looked at another aspect of the world through someone else’s eyes.

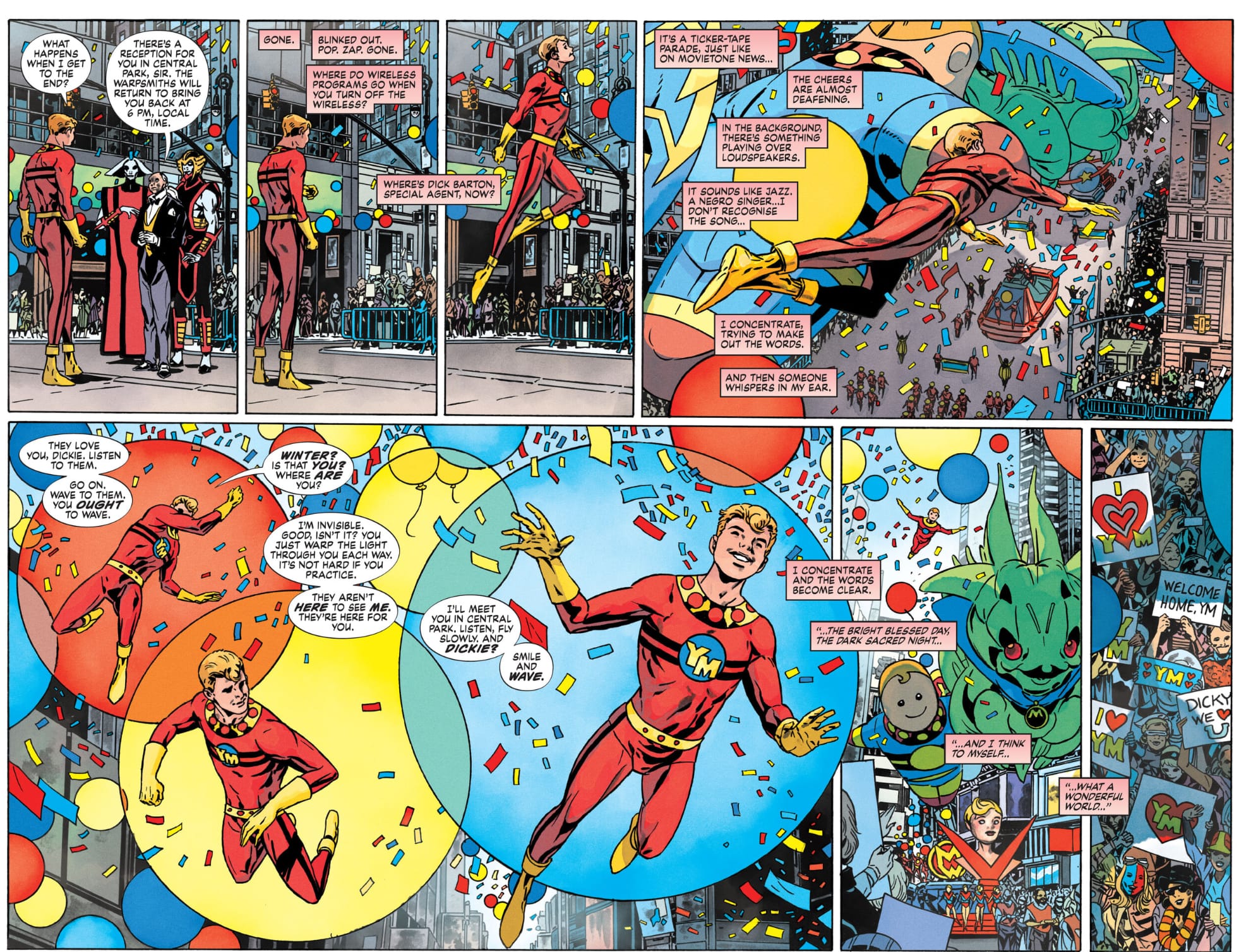

And now, after 30 years between issues, Buckingham and Gaiman return to explore “The Golden Age,'' but this time they narrow their point of view to one person– the resurrected Dickie Dauntless, aka Young Miracleman. For him, one day it was the early 1960s and along with his pals Miracleman and Kid Miracleman, he was flying to space to battle some aliens or something. And then the next day, it’s 2003 (that’s when this story takes place) and he’s waking up to a completely changed world. This is a superman seeing the world molded by the vision of a superman for the first time. And as he finds out, this was not the future that he was fighting for all those decades ago.

The story of Young Miracleman is the story of an angel. Or maybe it is the story of a ghost. Mark Buckingham’s Young Miracleman is a throwback to an earlier time when our heroes could be earnest, pure, and simply beautiful. If this was a movie or a television show, the character would always be shot with a soft light to give him a hallowed glow. That glow is part of the innocence of the character that Miracleman and Miraclewoman have seen dulled over time. Even by the end of Moore’s run, those two older characters had lost some of their angelic sheen as they had to make the tough decisions about how to remake the world. But Young Miracleman never made those decisions. He was killed in the 1960s and resurrected in 2003. But in his resurrection, is he more of a Lazarus or a Christ? Is he a believer or a messiah? Dickie Dauntless is brought back into this world to provide an anchor for this world’s god Miracleman.

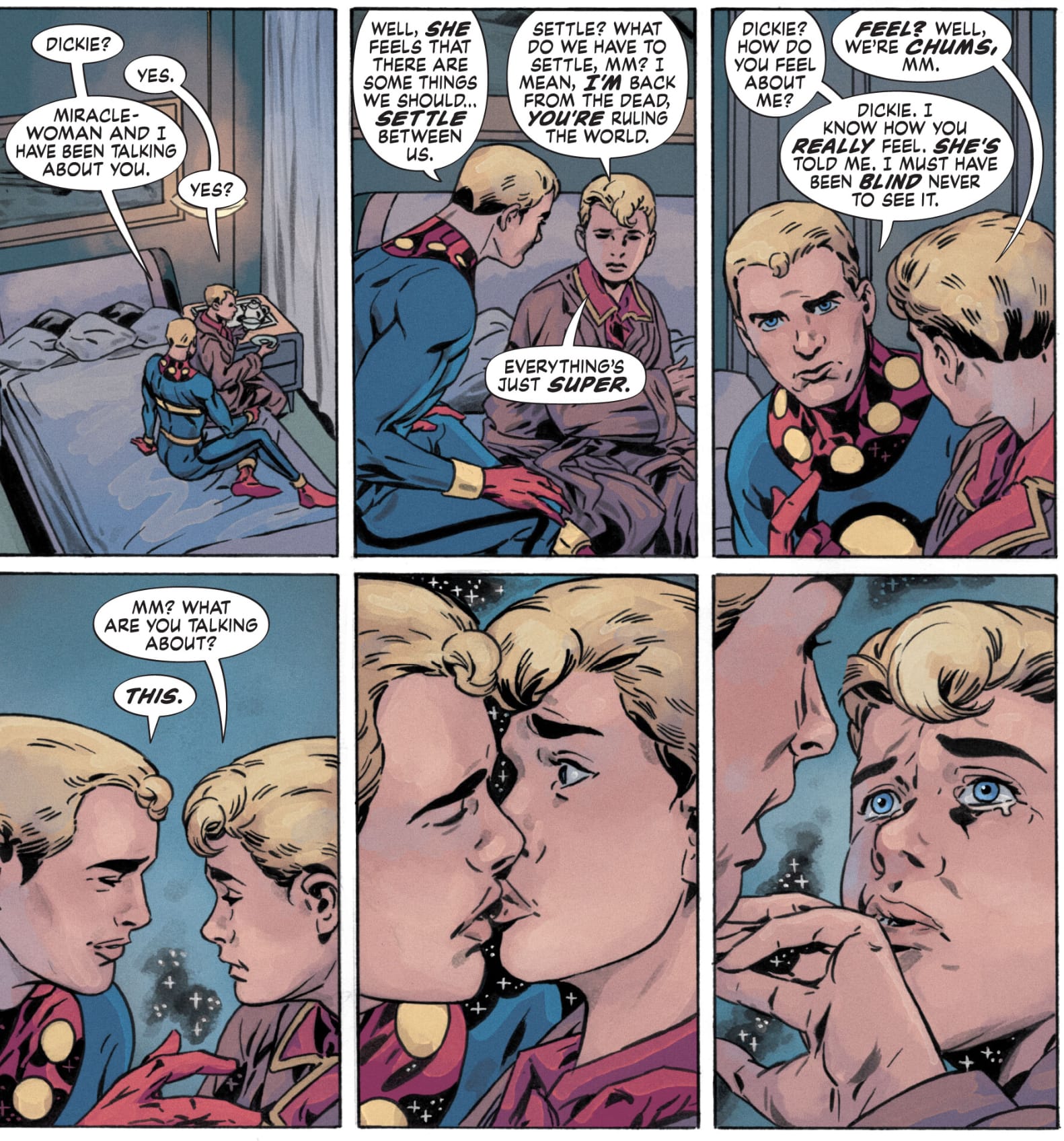

Ultimately, he’s brought back to give an old man redemption. After seeing how the world changed after the terrorized reign of the third member of the Miracle family, Kid Miracleman, Miracleman is lost. Gaiman doesn’t come right out and say it but it’s there in the subtext of this story. Miracleman only appears for a few pages here and there, mostly searching for Young Miracleman who ran away after Miracleman forces this confused kid to confront his own sexuality. But instead of dealing with the events in front of him, Young Miracleman runs away to the Himalayas (as superpowered beings do) and encounters other superpowered pilgrims there, including Meta Maid.

Young Miracleman is a recreation of a dead boy but he’s also a potential bomb in this brave new world. Gaiman and Buckingham underlie The Silver Age with an unspoken religious tone. This world that Miracleman has created is some kind of new Garden of Eden but is Young Miracleman the messiah of this world, part of the trinity of gods ruling over it along with Miracleman and Miraclewoman? Or is he the devil, determined to destroy paradise? After his travels to see the world, Dickie confronts Miracleman saying “This world sucks. And it sucks because it’s a bloody utopia. Your utopia.” And in the end, the subtext becomes the text: “If this is Eden, I’m going to be the serpent.”

So there’s a sense that Young Miracleman going forward into the next storyline “The Dark Age” will be the adversary, the serpent in the garden. But there’s another possible reading— he’s the Messiah overturning the moneychanger’s table in the temple. He’s been fed the line that Miracleman is this world’s new god so why shouldn’t he believe that means that he would be the serpent trying to overturn the work of the god? But as we read this book, Gaiman and Buckingham haven’t exactly set us up to believe that this is the way that the world should be. That it shouldn’t be in the image of superpowered beings who have placed themselves above normal people.

The difference between a superhero and a supervillain (between god and devil?) is thin, possibly just a matter of perspective. Miracleman has been the hero before. Alan Moore wrote him as a being who loved the world and almost couldn’t help but influence it in ways that he never intended to. The final issue of Moore’s run reads more like a man being swept up by events than setting out to remake the world in his image. And even with all of his allies, he never had anyone to tell him if he was wrong or right. Is it possible that for this story, Miracleman is the villain who thinks he’s the hero? And if that's the case, does Young Miracleman think he’s the villain even though he’s the hero? Is he here to redeem more than just Miracleman? Is he here to redeem the world? It kind of looks that way.

Since Gaiman and Buckingham first started telling this story back in the 1990s, we’ve seen our world reshaped by the idea of the superhero thanks to movies like Iron Man, Captain America, and The Avengers. Starting in 2008, superheroes became the language of pop culture so my son basically lives in a post-superhero world. There are elements of The Silver Age, where kids play dress up in superhero costumes and fight to save humanity that resemble the ways that kids used to play. For my son, superheroes have been a part of his world in a way that they’ve become just part of the natural fabric of it. So it’s fascinating to read Gaiman and Buckingham’s Miracleman, fictionalizing and fantasizing this aspect of the changes in culture that we’ve lived through.

Is this the same story that Gaiman and Buckingham would have told in 1993? And how has our view of superheroes in the world changed since they’ve become such a part of our culture’s DNA? They were once fringe but are now mainstream. That’s another part of the story that these creators are telling. In some ways if we’re old enough, are we Miracleman or Young Miracleman? Are we seeing the new world of superheroes through new eyes, seeing the changes, and wondering how the old world became this? Or have we grown so accustomed to how the world is now that we don’t recognize the superhero malaise that’s all around us?

Welcome to the future. Please tell me that it’s better than the past.

Comments ()