From The Archives- Harvey Kurtzman's Corpse On The Imjin

Harvey Kurtzman invited his readers into his stories by allowing them to participate in the story and not just merely reading what was presented to them.

One of greatest archiving projects of the past 10 years or so has been Fantagraphics black and white EC archives, with each edition focusing on a different artist. The Harvey Kurtzman volume just blew my mind, looking at the way Kurtzman drew these war horror stories. I was so used to him as a comedic cartoonist that seeing the same skills that he applied to MAD Magazine telling these hard war tales was shocking and just stunning.

This piece was published on Wednesday's Haul around March, 2013.

“I think what Kurtzman did ranks as some of the finest comics ever done. And I think, unfortunately, just because of the directions comics have gone in, it’s tending to be overlooked now. I hope it never will be forgotten.”

Archie Goodwin in an interview from BLAZING COMBAT

In many ways, I’m almost glad that I never had an appreciation for Harvey Kurtzman’s artwork before because I didn’t know what I was missing.

Since getting Fantagraphics’ CORPSE ON THE IMJIN AND OTHER STORIES BY HARVEY KURTZMAN, I’ve been obsessing about the man’s artwork. Mostly chalked up to a sad lack of access to the work, Kurtzman has been a name that I’ve known and could identify images that he’s drawn but I never took the time to really look at the way he told a story, particularly his war stories.

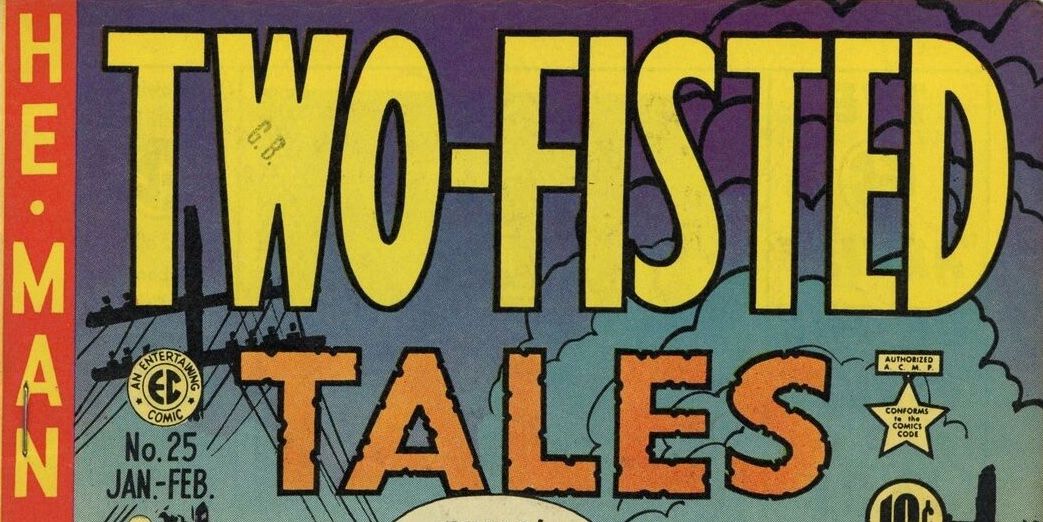

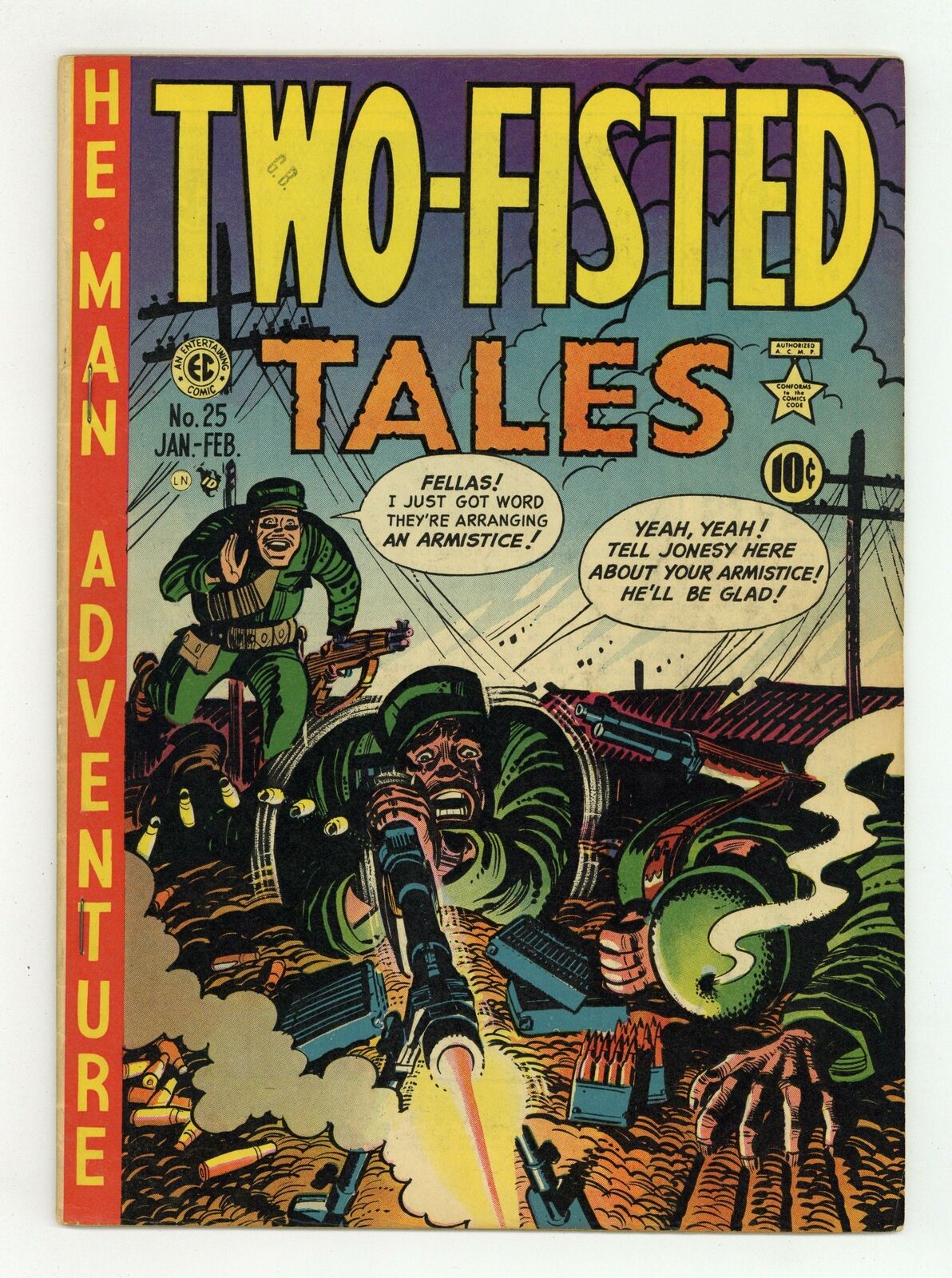

The thing that immediately jumps out at you is the man’s love of ink. While Fantagraphics’ new line of EC comics have occasionally been panned for the lack of color, Kurtzman is an artist who didn’t need his comics colored. With no disrespect to Marie Severin or any other colorist who may have been working on his comics, Kurtzman’s strong, bold, expressive and daring line tells you everything you need to know about his images. The way the bottom tier of panels in the above example (actually the middle tier on the actual page) gets blacker and thicker as the struggle becomes a killing shows just how dark this story and the character’s soul are becoming. It’s not that it’s getting dark because Kurtzman is tightening his shot on shadows but it becomes the soul of the story “Corpse on the Imjin” (from Two-Fisted Tales #25) because Kurtzman is drawing his own heart of this story here.

This panel sequence is one of many signature pages for Kurtzman’s war stories because of the horror that he’s getting at with as little detail as possible. The final two panels are practically abstract on their own. Kurtzman draws his own version of a journey into the heart of darkness in this tale of soldiers who have to resort to hand to hand combat just to survive. Kurtzman’s stories don’t have a “and you were there” feeling to them. Instead, he’s writing about war from a realistic point of view, he explores the idea of what war must be like on the human psyche. In “Corpse on the Imjin,” Kurtzman reduces that psyche to a growing blackness that devours the whole panel.

You could boil this whole sequence down into three panels but Kurtzman showed it in seven panels. Today we would call this decompressed storytelling but for Kurtzman, it was how he told stories. We can see this throughout the examples in CORPSE ON THE IMJIN, where Kurtzman would draw out time in these stories, making the reader really concentrate on the action being taken. He did it in stories he drew and in those that he just wrote and did the layouts for. The John Severin drawn “Marines Retreat” or Alex Toth’s “Dying City” both show Kurtzman’s structure beneath the images of those great artists. Even the Toth drawn “Thunder Jet,” this practically abstract aerial ballet shows sequences where Toth must have been clearly been following Kurtzman’s instructions.

The way that Kurtzman stretched out these scenes wouldn’t have worked in his humorous work in MAD or HUMBUG, where the joke is in the moment and then you move on to the next joke. But in these war stories, where Kurtzman is trying to depict the actions and consequences of battle, he prolongs these moments. In “Corpse on the Imjin,” the makes us witness one man kill another man. He could tell it in three panels (see above) but then it’s something that just happens. Prolonging it into seven panels, Kurtzman pulls us into something that we want to end, we want it to be over but the artist doesn’t want to let us off the hook that easily. He makes us witness the events, unable to help out either soldier.

In other EC books, while I can marvel at the artwork, I’m always slightly turned off by how mechanical they can feel. From the steely precision of Wally Wood or the glamour of Al Williamson, the lettering always feels like something I learned to do in my mechanical drafting classes back in high school and it just makes the comics feel colder than they should. In Kurtzman’s stories, the hand lettering is unique and alive. It feels like someone did it rather than using some guide to lay down the words.

That traditional EC lettering just wouldn’t have worked in Kurtzman’s stories. Kurtzman doesn’t have the classic lines of a Wood or a Williamson. He’s got a quick, dashed off, in-the moment mark making style that looks improvised and immediate. Kurtzman’s artwork exists in the now and is moving as opposed to a Wood who is trying to capture a scene or an environment. Kurtzman is capturing the soul of those moments with his line. His gestural drawings hint at the details that we fill in. Look at the way he draws the sleeves and clothes of the soldiers. You’ll never seen anything like that in reality but Kurtzman makes you believe every line because he believed in every line. He would simplify his drawing his drawing over time, making his humorous cartooning more wispy and whimsical but he could make you believe that his images we as solid and concrete as the items or events that he was recreating.

Kurtzman put down ink lines in ways that shouldn’t work. The image of a tank from Two-Fisted Tales #24 shouldn’t look like a machine of war but Kurtzman sells it. There’s no details to the drawing except for what we fill in. That’s how a lot of his war stories worked. A great artist, he still lets us do a lot of the heavy lifting when we look at his comics, from his war stuff to his humor. Kurtzman invited his readers into his stories by allowing them to participate in the story and not just merely reading what was presented to them.

Comments ()