Charles Soule and Steve McNiven Explore Ghosts in Daredevil: Cold Day in Hell

Frank Miller casts a long shadow over this story and Charles Soule and Steve McNiven know it.

Daredevil: Cold Day In Hell #1-3 by Charles Soule, Steve McNiven, Dean White, & Clayton Cowles (Marvel Comics, 2025)

Matt Murdock, the superhero known as Daredevil, has always been a haunted character. Going all the way back to 1964’s Daredevil #1, written by Stan Lee and drawn by Bill Everett, the inciting act that leads to Murdock becoming a superhero isn’t the chemical spill that blinded him and gave him superpowers. It’s years later and the murder of his father, a boxer, was killed after he didn’t throw a fixed fight. That first issue establishes that Murdock’s driving motivation is making up for the death of a loved one. And then the deaths would just keep on coming over the years and decades of stories—Elektra, Karen Page, Heather Glenn. These deaths are part of the mythology and the guilt that continues to drive Murdock today. But more than any of those past loves and family, there is one ghost which haunts Daredevil and all of the writers and artists telling his tale more than any other— Frank Miller. Since Miller’s first run on the character in the early 1980s, nearly every story every creator since then has had to live in the shadow of Miller and his classic stories. Some try to dig deep into recreating the Miller atmosphere and others try to run away from it as quickly as they can. But whether it’s Brian Michael Bendis, Ed Brubaker, Mark Waid, or Saladin Ahmed, Frank Miller casts a long shadow over the stories they told. In Daredevil: Cold Day In Hell, writer Charles Soule and artist Steve McNiven embrace Frank Miller’s hold on the character in intriguing ways, including engaging in another Miller classic story, The Dark Knight Returns.

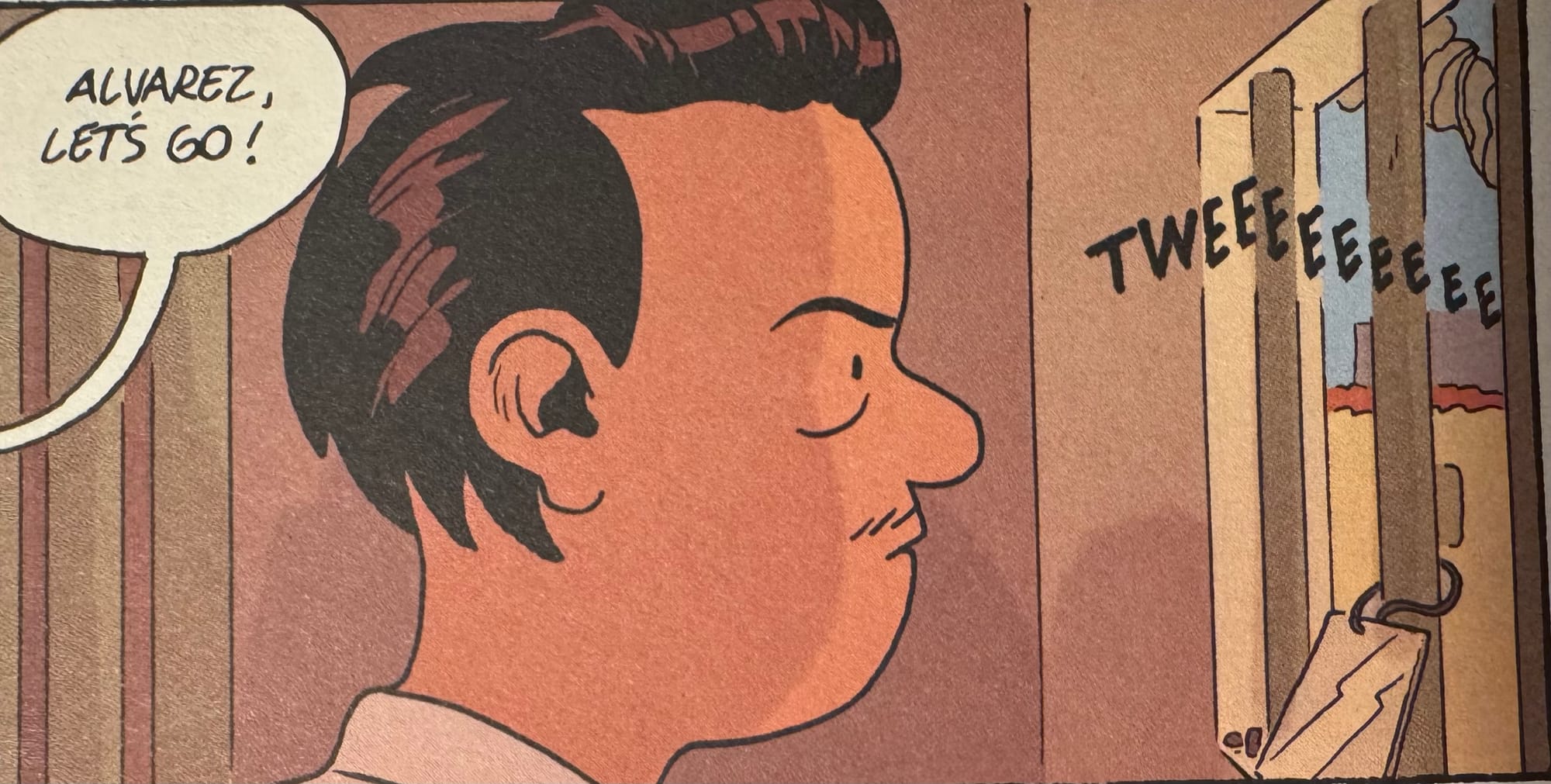

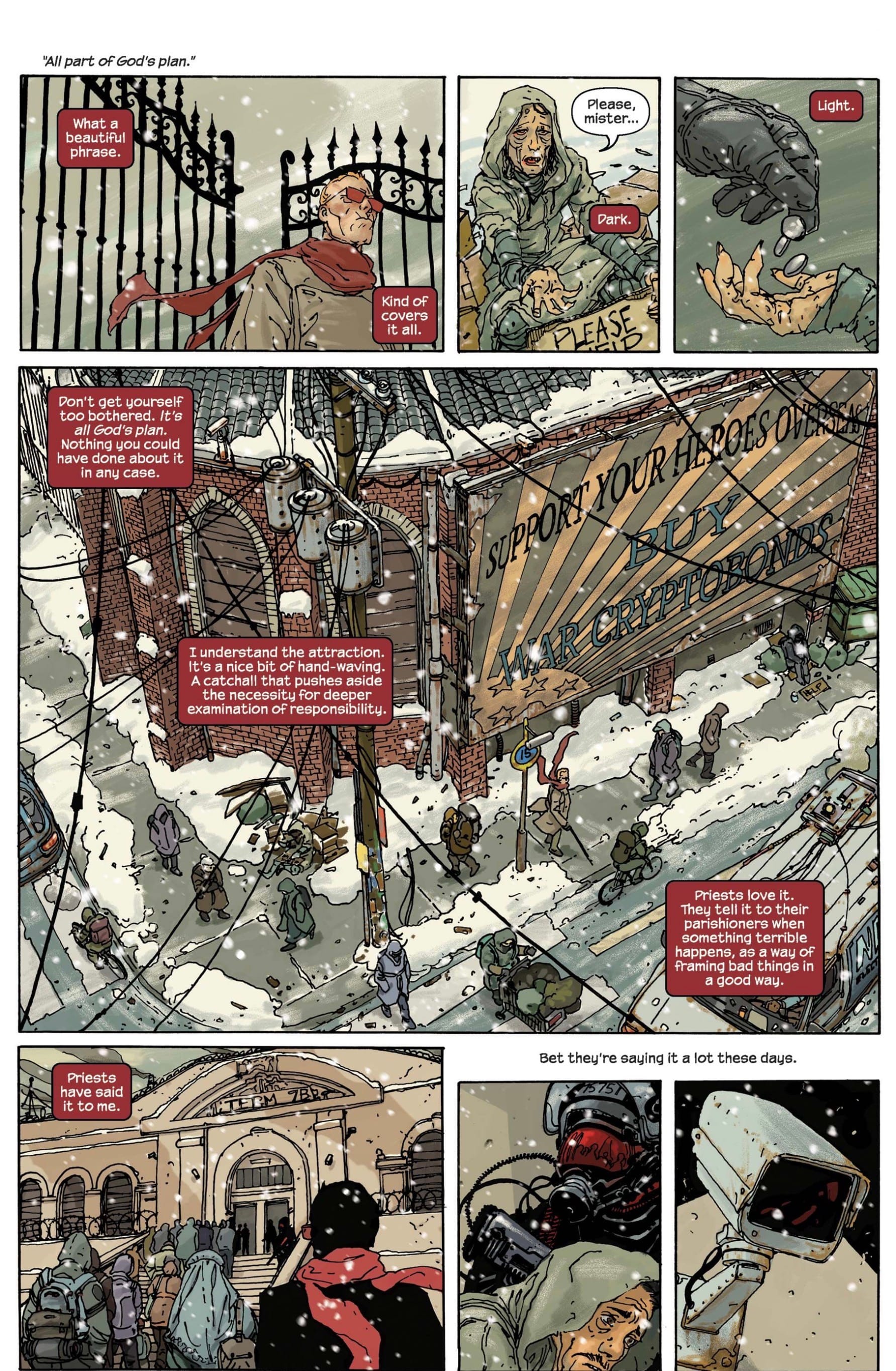

As the story opens, Matt Murdock is no longer a superhero or a lawyer. He’s an old man running a soup kitchen, his powers long ago faded. Of all the roles he’s tried to assume over the years, this seems the most appropriate for the character— his Catholic guilt finally leading him to serve people in a simple yet vital way. Returning to a war-ravaged Manhattan after visiting an old acquaintance’s grave on Staten Island, Murdock reflects on his life and how it has been “all part of God’s plan.” At least, that’s what he tries to convince himself. “Priests love it. They tell it to their parishioners when something terrible happens, as a way of framing bad things in a good way” he muses. “Framing bad things in a good way” is practically the story of Daredevil. After a subway explosion triggers the reactivation of his heightened senses that made him Daredevil, Murdock finds himself embracing his old superhero ways to protect a young girl who is the hunted by an old adversary, Bullseye.

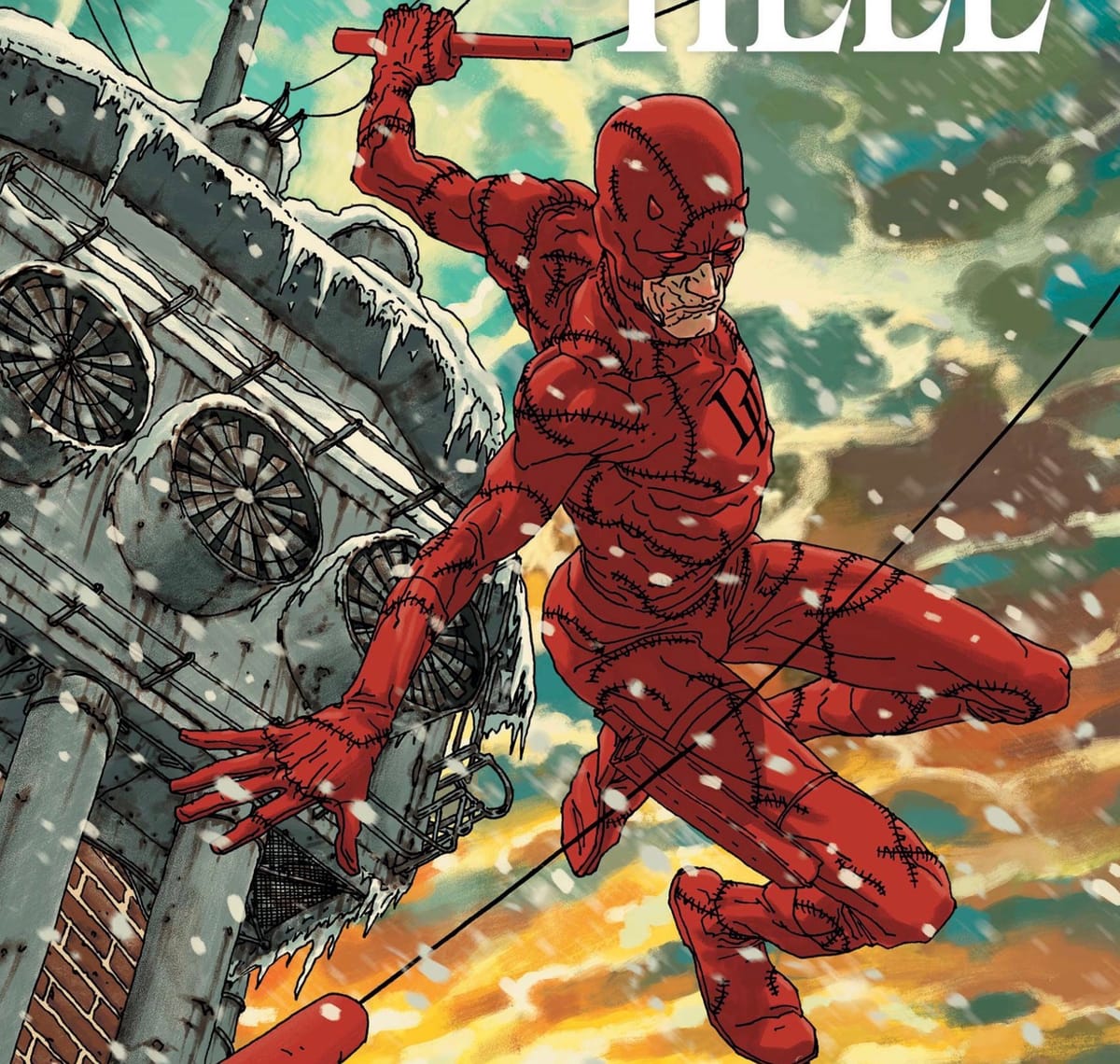

It is not hyperbole to say that Soule and McNiven want to do The Dark Knight Returns for Daredevil, aping everything from the aged-out hero to Miller’s 16-panel page. And honestly, they do a decent job of it. Even if Cold Day In Hell lacks the visceral punch of DKR, there are enough creative flourishes to engage with, particularly in McNiven’s art. Thanks to his thin lines and the painterly coloring by McNiven and Dean White, these comics most closely resemble Miller and Lynn Varley’s underrated Elektra Lives Again more than they do other, more iconic Miller artwork. McNiven and White convey so much of the story like the cold atmosphere or the age of the characters. It’s more than just drawing a few lines to signify wrinkles— it’s Murdock’s stitched-together costume, making it look like he could just unravel completely at any time. That barely-holding-it-together physical appearance sharply contrasts with the images of Daredevil acrobatically bouncing around the Manhattan skyline. In McNiven’s images, we get the thrill of a hero having his one last hurrah contrasted against the frailty of his physical frame. McNiven conveys that it is just a matter of time until his body will come apart and fail him.

McNiven is leaning a lot into Miller’s visual language without ever going so far into obvious fannishness that it becomes distracting. It enhances the story as it grounds the story in a sense of history. That history is just another of the many ghosts found in these pages but the more subtle ghost of the story. McNiven’s Daredevil isn’t the sleek fighter or handsome, devil-may-care swashbuckler he often is. This isn’t even DKR’s Bruce Wayne, whose physical stature is still large, solid, and intimidating. Cold Day In Hell goes in the opposite direction, embracing the characters’ age and the years that have passed. Murdock and Bullseye are old men and look like it. The Punisher, a tertiary character in the story, is clearly a victim of the years and wars that he’s fought, well beyond his prime as his anger has only grown over time. McNiven doesn’t even try to pretend that these characters can possess a fraction of the vitality they once possessed as they suit up for one last hurrah. In fact, the only character who appears as vital as ever is Elektra, a brief but fascinating mystery that has us wondering what her story is.

And yet, the story rarely stays with any of these ghosts long enough for them to have any real impact. Images and memories of Murdock’s past life float in and out of this story offering Daredevil’s greatest hits without leaving any truly lasting impressions. They’re present to say “hey, here’s Elektra and there’s Foggy Nelson. You remember them, don’t you?” They’re signposts of old stories and wounds for Murdock but don’t alter the future with their appearances. Captain America and Daredevil aren’t characters who have a strong connection but in Daredevil: Born Again, Frank Miller had Murdock describe Captain America in a way that will forever bond the characters. In Daredevil #233 (July, 1986 ) when Daredevil describes Captain America as, “A soldier with a voice that could command a god and does,” Miller created this great link between the character; this description could only come from someone whose main experience with Captain America was an aural one and not a visual one. A blind man is not going to describe what Captain America looks like.

So it makes sense that Soule and McNiven use Captain America to set a repowered Matt Murdock on his path to rescue someone. Captain America wasn’t commanding a god but he was commanding Daredevil to take up the fight once again. But the moment is so thin that it seems wasted— it’s just a cameo, creating some ties to a larger Marvel world, but nothing more than that. And this story is full of so many moments like this— these callbacks to older Daredevil stories that could create real meaningful echoes in this story but instead are just thin, inconsequential ghosts of meaning. They are empty Easter Eggs of past stories, having meaning only in the past that they reflect rather than adding anything meaningful to this comic or to Murdock’s journey. Captain America, Foggy Nelson, Elektra, and the Punisher show up as a lot of noise in the story but miss the way that Miller used them to challenge or support Murdock. In Cold Day in Hell, they are important only as they represent the past but they add nothing to the story; it could have been told without any of these ghosts showing up and would not have missed any beats.

What this ends up really being once you strip out all of the unneeded fluff is the final confrontation between Daredevil and Bullseye and that’s where this gets interesting. You have the Catholic trying to reconcile everything happening in the world as being “part of God’s plan” with a madman. “… we’ve lost what made us powerful,” Bullseye broadcasts to the city as he’s about to unleash his final weapon. “We’ve forgotten how to dance. The wonder of seeing someone try to destroy everything for reasons we can’t understand. The stakes so high you can’t even breathe… We’ve forgotten.” He’s talking to all of NYC but he may as well be talking only to Matt Murdock. Here we have a hero who has found something akin to contentment after his superhero life and a villain who just wants to blow up the world to feel something again. Bullseye wants his old playmate back.

Here’s where Soule and McNiven’s story feels vibrant— when it gives room for these two characters to exist in opposition to each other. It’s a story about a man who just wants to move on with his life versus a man who wants to recreate the past. So maybe Bullseye is just another ghost of Daredevil’s but one who has more of a pull on him than these others do. There’s just not enough room in this story given to that idea to make it anything more than a possible suggestion of this conflict Frank Miller used the 16-panel page in Dark Knight Returns to cram as much text and subtext into those four issues. Soule and McNiven just never use the format to stuff as much story into every page and Miller did. Daredevil: Cold Day In Hell feels so light and airy compared to DKR.