Cease the Means of Production - The First Issue of Juni Ba's Monkey Meat

Juni Ba questions both how much we are being manipulated, but also how willing we are to allow ourselves to be manipulated. This worldview is what makes his satire that biting

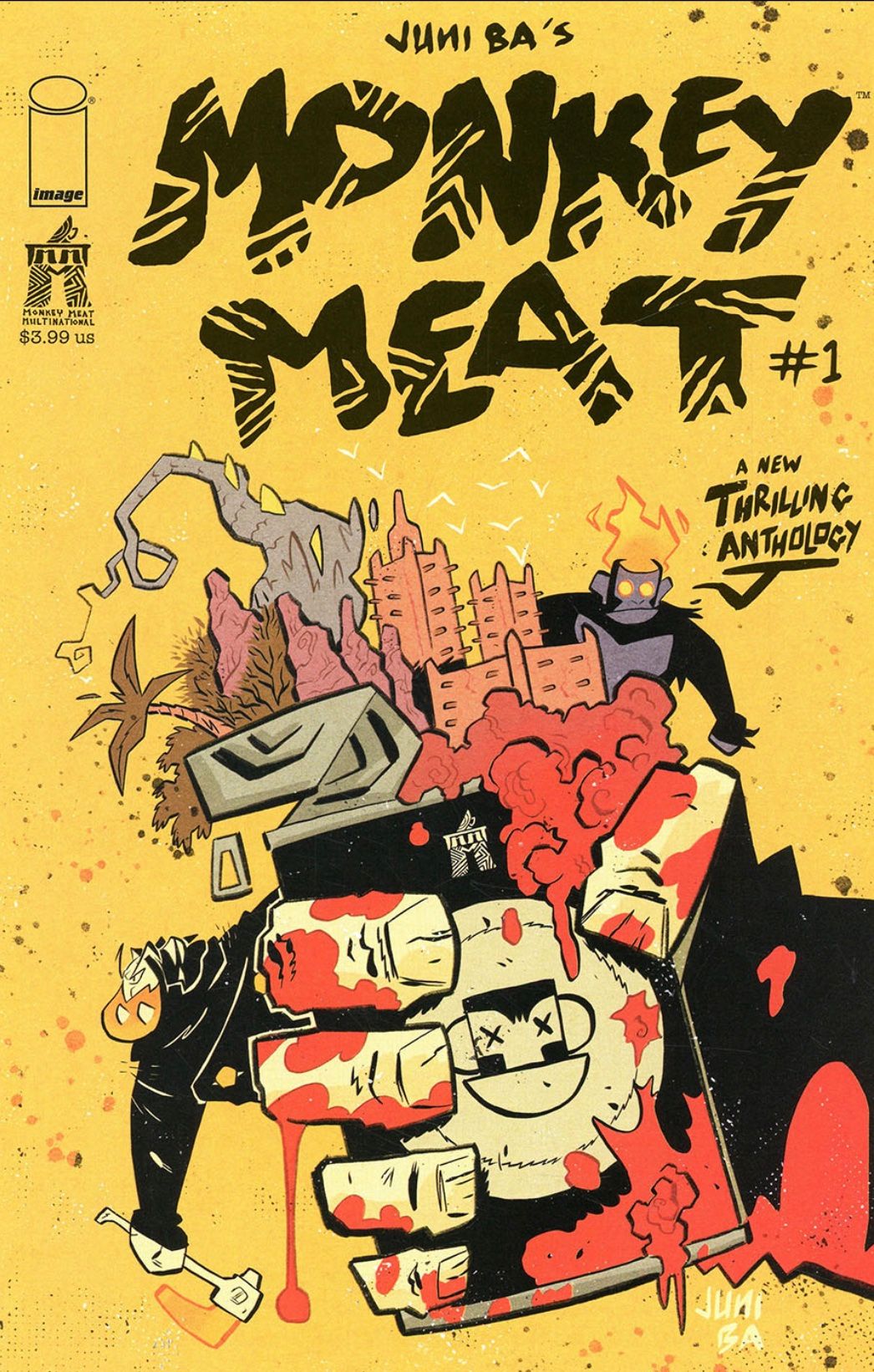

I'm going to level with you. I was highly anticipating this comic. Between following Juni Ba on Twitter and reading his 2021 West African fantasy graphic novel, Djeliya, I have been sufficiently hyped for the young cartoonist's next project. That anticipation culminates this week with the publication of Monkey Meat, Ba's anthology mini-series for Image Comics that is a delightfully bonkers, gonzo satire. In a mere few months from the release of Djeliya, Ba shows growth as both a visual and narrative storyteller with Monkey Meat. He feels more pointed, more realized as an auteur. This first issue indicates that Ba is aiming for a mode of satire that will feel like a higher-octane version of Mark Russell.

Initially, I think it's important to recognize how cool it is that we get a series like this from a mainstream publisher. There is definitely a different feel to a serialized comic, and it's clear that Monkey Meat benefits from a type of episodic pacing. Seeing a creator handle the entirety of a publication for a company like Image is fulfilling in and of itself. The process of something like Monkey Meat is usually reserved for original graphic novel territory, smaller presses, or a novelty line. Not that there would be anything wrong with this being a small press or self-published book, but something is refreshing about it being in the Wednesday Warrior realm. Moreover, it's additionally refreshing to see someone like Ba, whose style is anything but conventional, publishing through Image. It's a feeling akin to reading early Lemire when a reader can tell a cartoonist is just as comfortable on the fringes as they are with the Big 2.

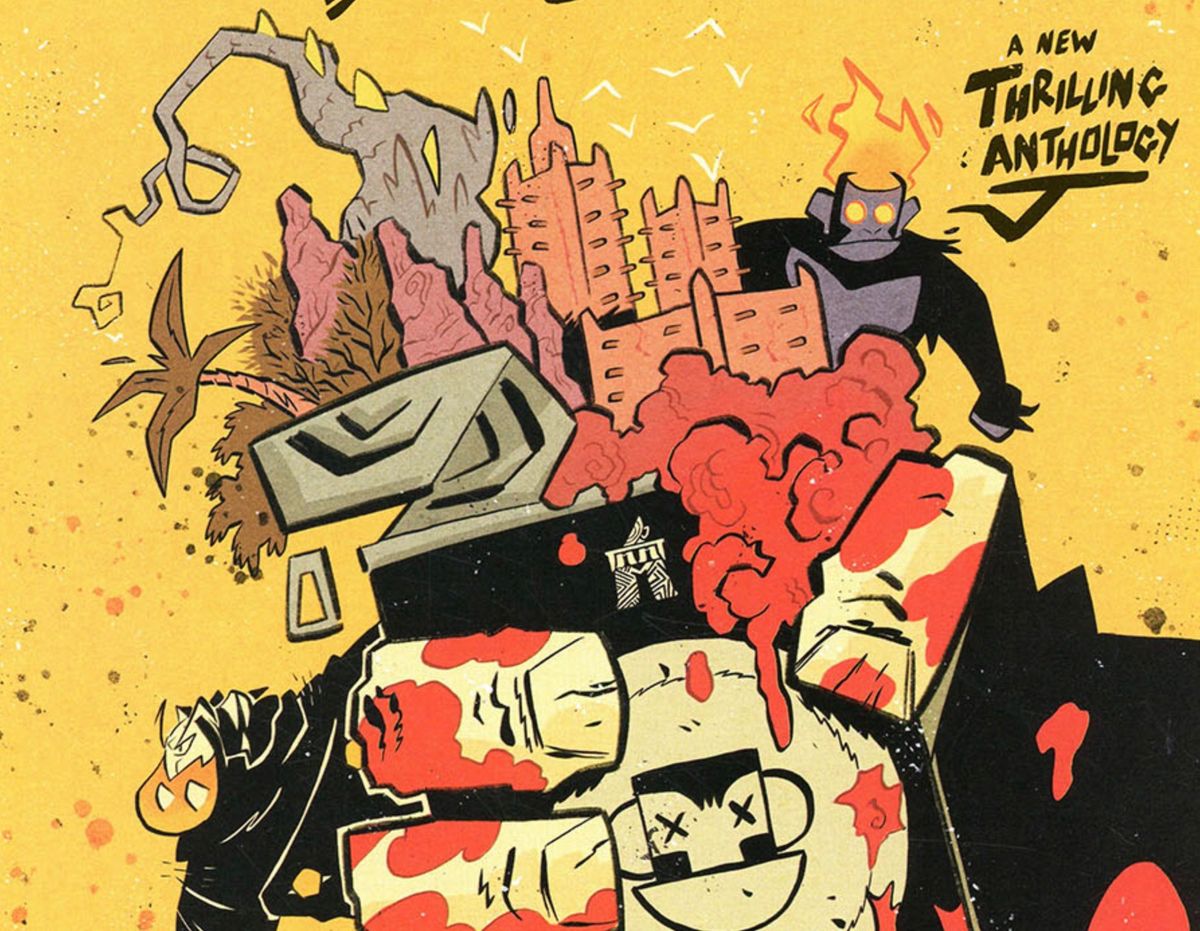

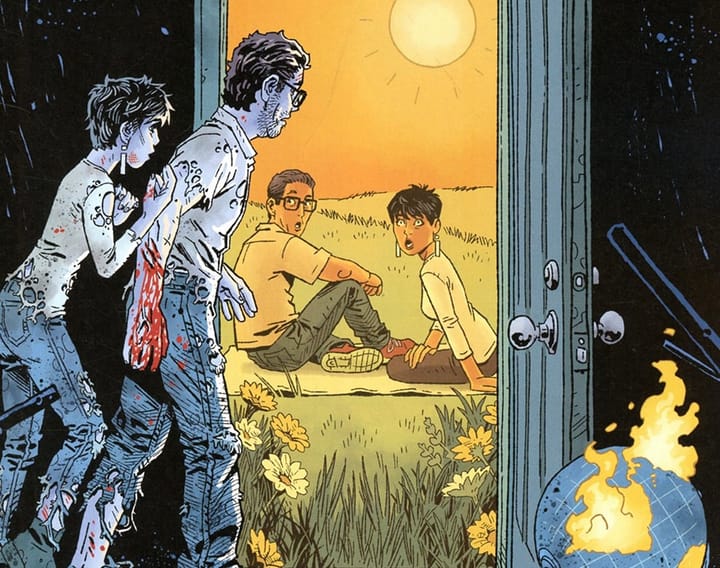

So, what about his style? Believe me, I'll get into what Ba has to say in this issue, because, for me, it is what makes this book land so well. But what makes this book take off is Ba's art. His pages are bombastic mosaics of pulpish pop art. He works in caricature - people and things resemble what they really are, but nothing is ever entirely precise. Of course, this lends itself to the fantasy and science fiction that guide his storyline, but it also lends the book - one that is particularly scathing when all is said and done - a sense of whimsy. His line structure can be both angular and flowy, two ends of geometry somehow working in concert. You can sense the thickness on each page - thick lines (particularly outlines) and thick colors. His color work is what captivated me most of Djeliya, and it's on display in Monkey Meat as well. Ba uses a specific set of earth tones for most of his coloring. Most of the time, the shades are one or two degrees off from what might occur naturally. Again, the color has the effect of both heightening the fantastic while providing a dose of whimsy. Altogether, this evokes a certain style. I see influences in place - some Darwyn Cooke and Kyle Baker, but even more so a 90s cartoon-inspired aesthetic of Genndy Tartakovsky, Bruce Timm, and the entire Nicktoons lineup. However, these antecedents seem to inform more than define, and Ba's style is an aesthetic to itself. Again, it makes me happy to read something like this in a Wednesday floppy.

Honestly, I think anyone could simply stare at Ba's pages and get their money's worth. I think I might have allowed myself to get distracted often while I read Djeliya, often needing to flip back to figure out what plot point I missed. To be fair, I also would contend that Ba's storytelling has also improved, and that's important because he's making a strong statement with Monkey Meat.

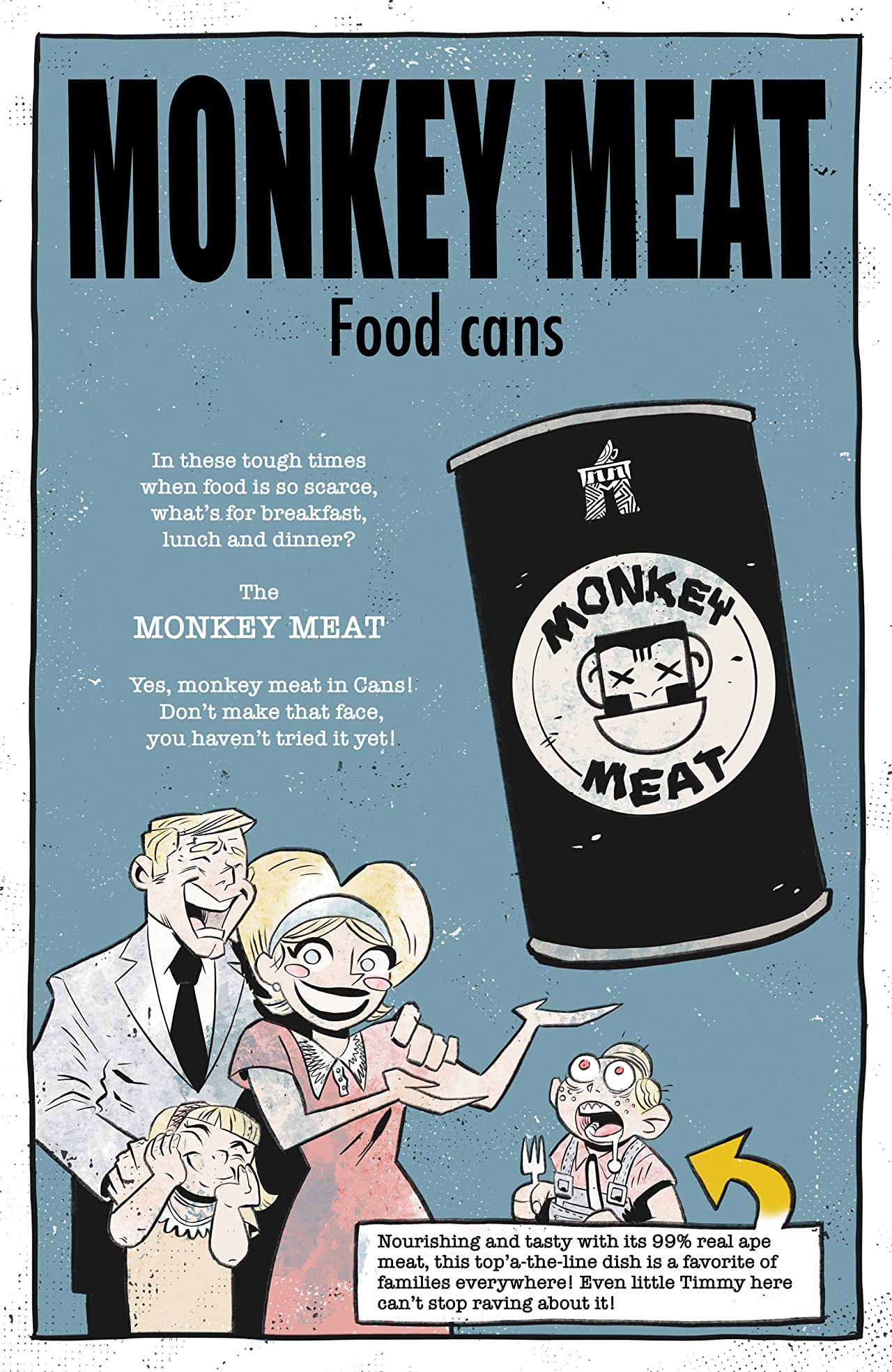

The focus of the book is the eponymous Monkey Meat Multinational, an equal parts nebulous and nefarious organization that is a stand-in for, oh, so many things - multinational companies, governments, the broad-sweeping colonizing apparatus, West African chattel slave-trade, displacement of indigenous populations, modern capitalism, late capitalism, capitalism as a whole, shoot, speciesism, maybe even feudalism. Djeliya wasn't without its socio-political commentary, but Monkey Meat puts it at the forefront. Even the name of Monkey Meat Multinational taps into the way companies shape our linguistic worldview. It is subtle, but Ba notes early on (pictured above), that the canned meat is 99% real ape meat. Accurate nomenclature is irrelevant - Monkey Meat is clearly a better name, what with its alliterative appeal, than the alternative.

"To preserve their privacy, the owner of the Monkey meat company copyrighted and forbade the use of their own name. Because they can."

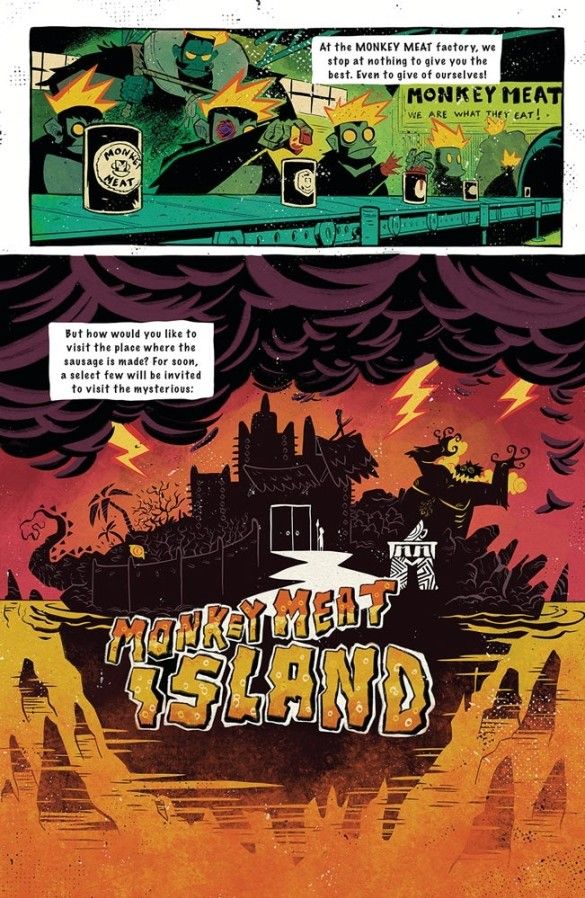

The issue opens with a commercial advertising a contest for the chance to win a tour of the Monkey Meat factory. The advert proclaims, rhetorically, "But how would you like to visit the place where the sausage is made?" It's with that line that I realized how serious of a satirist Ba was going to be in this series. He personifies the exact way gigantic, bloated corporations openly flaunt their faults, thumbing their collective noses at any attempt at regulation or basic human decency. I mean, they're selling canned ape meat. Scruples don't exist in this world. It's a step away from cannibalism, but, hey, what are you gonna do?

Remember that line from Usual Suspects, "the greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he didn't exist"? What Ba taps into is the way corporations don't even consider such a notion anymore. There is no need to hide, no need to convince the general public of some altruistic underbelly. We've fully given into the Dead Kennedy's proclamation, "Give me convenience or give me death." It's a both/and situation here - Ba questions both how much we are being manipulated, but also how willing we are to allow ourselves to be manipulated. This worldview is what makes his satire that biting. It's easy to go after the elites. It's almost, to some degree, inconsequential in the big picture. But it is far more difficult to point the mirror of satire back at the reader. We might not be the "big bad," but we're not without blame either. Good satire like this should make the reader a little uneasy; it needs to provoke some sort of reflection or re-evaluation. Otherwise, it would just be another screed against corporatism. And while that's always good fodder, it only tells half the story. What I find impressive about Monkey Meat is precisely that scope.

As I mentioned above, regardless of the content, Monkey Meat is a visual treat. But the content, specifically the narrative structure and Ba's specific phrasing, is what drives the book and - most importantly - gives us a feel for the type of creator Ba is going to be. He frames the narrative in two ways, using both a faux commercial propaganda message to set the exposition for the story, and later transitioning to the Monkey Meat mythos. He taps into the mode of fantasy legend storytelling that defined Djeliya, executing a succinct setup for the story that paints the evil backstory for the company while also providing us a dubious protagonist of sorts in the personage of Thaddeus Lug, a sellout turned apostate revolutionary, a wonderful stand-in for every one of us who complains about the exploitation of the developing world and their mineral-rich natural resource deposits while typing our screeds on our iPhones.

It is with the choice of language that I think Ba shows his growth as a storyteller. The man knows how to craft a page, and his work as crafting the narrative through the use of panels is increasingly tighter. But satire like this needs a deft use of language, and Ba finds a sharp voice in Monkey Meat. Word choice is incredibly important - for the jokes to land, for the targets to be hit, the words need to be precise. That is what allows Mark Russell to be continually successful with his satire, and it is exactly what is on show in this debut issue.

Ba drills to the heart of the chasm between the haves and have nots, brilliantly channeling the sociopathic mindset of the corporatists. It is over the top enough to be farcical without entirely self-indulgent. There is a balancing act here, and a dip in either direction either leans too absurd or too soft. It is also important, if one wants to mock the type of language used by elites, to be consistent in that use of language. Ba exemplifies the "party line" style of the elite, casting the native population as freeloaders who had been living on the island "rent-free." He consistently repeats this phrasing, driving the idea home that, for the plutocrat class, everything is a commodity. Ba writes of Monkey Meat Multinational's initial land grab, "the only issue was how to dispose of the raggedy lot who previously occupied the space with no claim." He can thus easily create the allegory for slavery, colonialism, indentured servitude, company towns, and neo-feudalism that feels both informed by history and incredibly relevant to current events.

By the end of the issue, we've experienced a brief history of Monkey Meat Multinational and its first experience with a rebellion. As Monkey Meat is an anthology series, I'm curious to see what threads Ba continues to pull following the set-up of this debut issue. He repeats a metaphor about a game of cat and mouse, explaining that eventually, the cat needs to understand that, for the mouse, it has never been a game. Is Monkey Meat Multinational too big to fail? Perhaps there is "no need to worry about a hapless revolutionary.

Comments ()