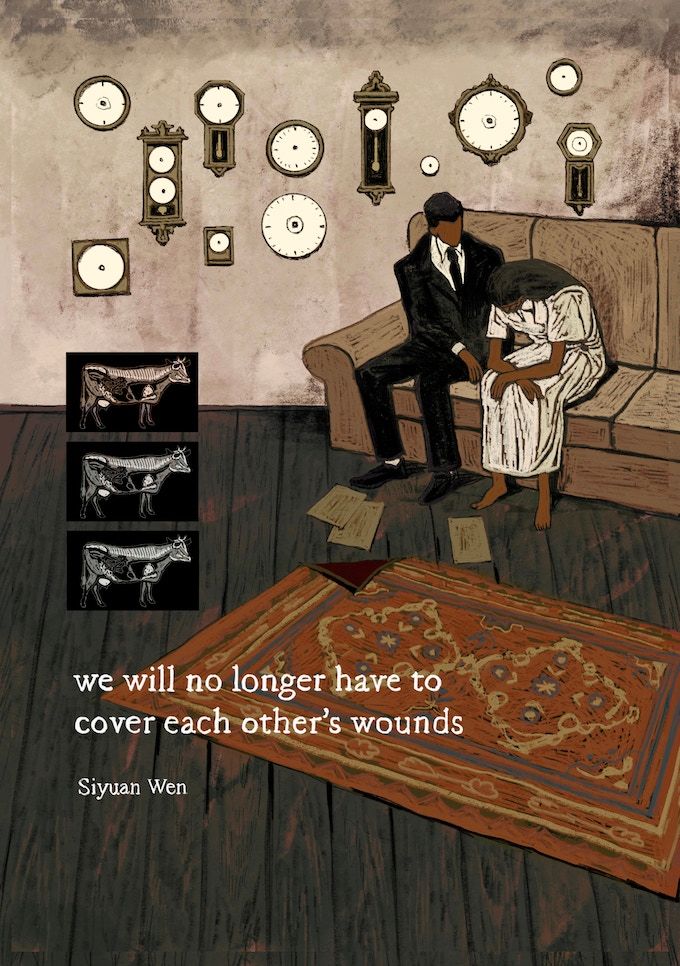

Advance Review: We Will No Longer Have To Cover Each Other’s Wounds by Siyuan Wen

Call it empathy or just a collective response to loss but Wen’s pages draw you into Anna and Wayde’s presences to create a triangular bond between the two characters and the reader.

Disclaimer: Fieldmouse Press provided a review copy of this book. Even before they did that, I had supported this book through their Kickstarter campaign which runs until August 9th.

I have also been a supporter of Fieldmouse Press through their Patreon for their online literary journal Solrad.

There’s a push-pull happening in Siyuan Wen’s We Will No Longer Have To Cover Each Other’s Wounds. Actually, there are a lot of different types of pushing and pulling happening in this book as a man wrestles with the memories of his late mother. There’s the back and forth between the past and the present, between a mother and a son, between what is happening and what is a memory of what happened. On nearly every page, Wen crafts this tension between what is and what was, either through his text (his drawings and words) or through something just below the text, something unseen but felt through the images. Call it empathy or just a collective response to loss but Wen’s pages draw you into Anna and Wayde’s presences to create a triangular bond between the two characters and the reader. But maybe it isn’t triangular but more linear, with Anna and Wayde being the two endpoints and the reader acting as an outside force that mediates how close or how far apart those points are depending on their reading of this story. So maybe we’re the ones doing that pushing and pulling.

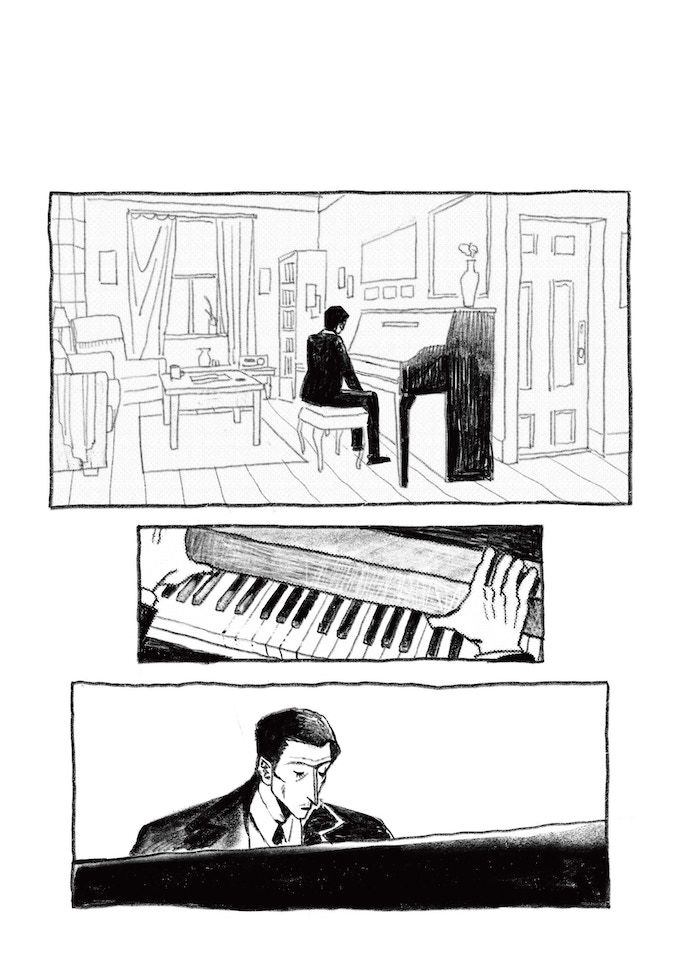

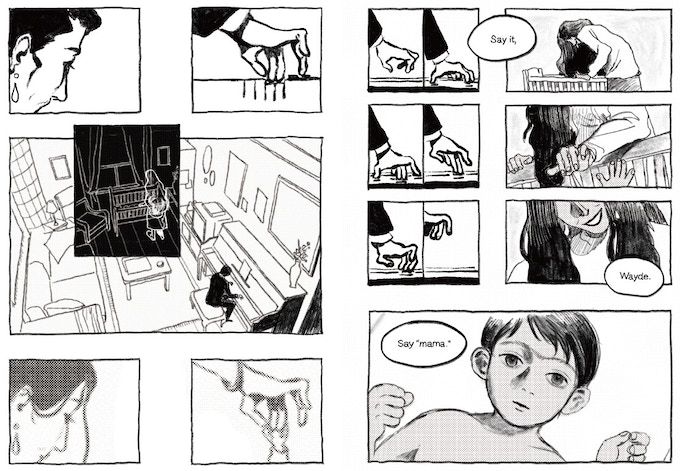

We read this story as Wayde’s story, the son left by his mother to go through her belongings and his memories just trying to make some sense of everything. Sitting in his mother’s apartment and playing her piano, Wen brings Wayde’s memories to the foreground as a young Anna stands over her young son’s crib, holding her hand out to tickle Wayde as he’s tickling that piano’s keys in the present. “Say it,” she coaxes her son. “Wayde. Say ‘mama.’” It’s such a motherly thing to ask but the boy just stares up impassively, eyes wide taking in the world around him but not giving her mother what she asks for. She picks her one up and dances around the room with him as decades in the future he plays the piano just for her. The words “I love you so much,” hang in the air, between the gutters of the page but who said it- the son or the mother? Or both?

This opening sequence of a mother and son being so present for the other but not getting what they want or need from the other speaks so much to this relationship. In life and in death, Anna and Wayde seem to be there for one another when needed without being present for the other as they would be looking for from their mother or their son. They occupy the same spaces and memories but for Wen, there’s always a gulf between them, whether it’s a physical space or it’s the time between memories. So after his mother dies, Wayde is left alone to close that space with the memories.

Filling in that emptiness, we’re left to figure out what kind of mother Anna was and what kind of son Wayde was. The answer to that seems to be that they were mysteries to one another. We move through this book with Wayde witnessing the remains of his mother’s life— an apartment filled with years of relics of a life and fragments of memories that a mother passed down to her son. It’s through these fragments and memories that we get to know both of them as much as they and Wen allow us to. Wen manages to be both open with these characters and protective of them as well. We only know them through what Wayde remembers. So we see Anna through his memories but we also see him through what he remembers. What we see is what’s important to Wayde at the moment; what’s important to him as he uncovers and curates his mother’s life.

Wen creates this visual poem for his explorations. There’s a rhyme and meter to his pages that are told through specific narrative movements that require us to spend the time with them, trying to see beyond the text to get to an interpretive reading of this story. He uses different drawing tools, everything from pencil to paint to draw us into this poem. Nearly every drawing and word in this book has some meaning beyond the surface level. And he knows what he’s doing. “You locked the spinning ceramic dancer forever in a worn music box,” Wayde reflects about his mother. “I was too young to understand what metaphor was, to comprehend that kind of mental divergence, relentlessly attributing strong signs to ordinary objects.” That’s what Wayde and Wen are both going through now, finding the artifacts of a life but trying to decipher their meaning and significance. Wayde was looking for his mother to offer some cipher in her belongings just as we explore these pages to find the guideposts that Wen is laying for us to follow him.

Anna is the void in this book that we’re all trying to fill. She’s a mystery not to be solved but to be put to rest. At one point, Wayde talks about how there was no funeral when his mother died and even how he didn’t understand her death until he found a photo of her in a drawer. He moves into her apartment as if to fill that void. Anna’s name is scratched out of the mailbox label and Wayde’s is written above hers. It’s as if the only way to understand her is to inhabit the spaces that she did. Wen’s characters, both the son and the mother, are looking for a connection in death that they couldn’t find in life. She has left these things for him, curated a story for him through these knickknacks she accumulated, and now he has to read them and figure out what her life and her death mean to him.

And we’re here to both witness this and to come to our own understanding of these lives and Wen’s work here. We’re placed in this odd role of being a mediator as well as an audience for Wayde and Anna. Wayde may be trying to understand his mother but we’re trying to understand both of them. Wen pulls us into these lives to the point where they both haunt us even after we get to the back page. You’ll want to immediately flip back to the first page, rereading this with the knowledge of these people that you’ve picked up on the first read. You’ll want to use the gained knowledge to go back and see what you missed the first time around. And then when you get to the end of the book for a third time, you’ll go back to the first page and want to dive right back in. Siyuan Wen’s We Will No Longer Have To Cover Each Other’s Wounds starts to work on you, transferring both its wounds and its healing to you. And it’s something that you’ll want to experience over and over again.

For more preview art, check out the Kickstarter campaign and also their announcement on Solrad for this book.

Comments ()