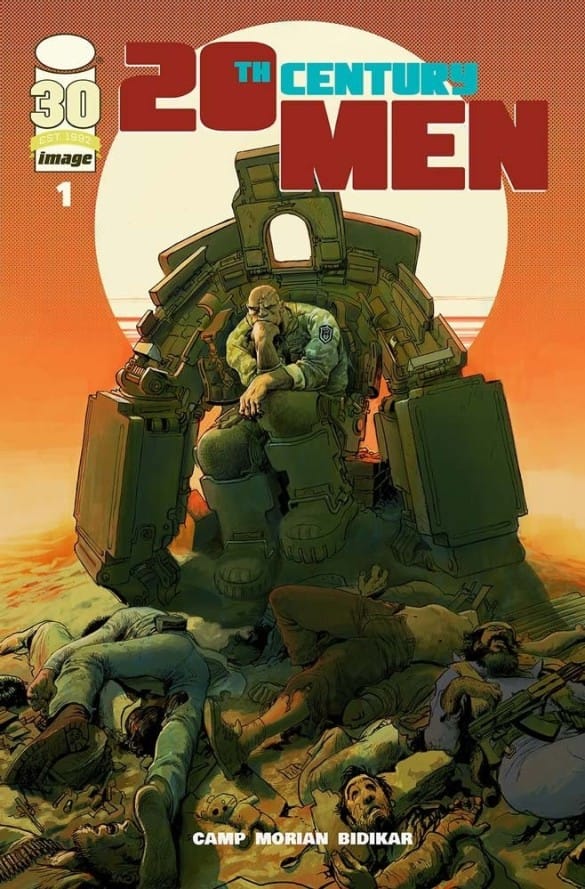

A Politics of Dream - Thoughts on 20th Century Men by Deniz Camp, S. Morian, and Aditya Bidikar

20th Century Men doesn’t overtly bill itself as a superhero comic. And to be fair, it shouldn’t. It is a post-superhero superhero book.

I wanted to finish up this short piece last week, but the opening of school got in the way. Nonetheless, I was impressed by the first issue of 20th Century Men, and I believe it’s the type of book worth exploring because of the ideas the creative team pushes through the narrative.

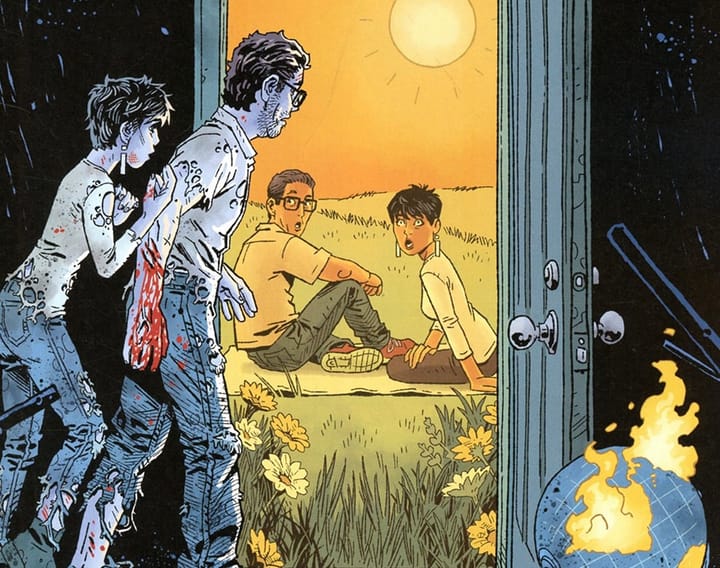

20th Century Men has the aesthetic feel of a different era of style of comic book. Twenty years ago, this book would feel perfectly at home at Vertigo. In visual style, it feels like it could have been a series of 2000 AD strips from the mid-90s. And despite being published by Image, 20th Century Men recalls a quality that hearkens back to the heyday of Image’s early 10s campaign where it would have fit perfectly aside big-idea science fiction books like East of West, Black Science, or Nowhere Men. I make these comparisons because, like the aforementioned books, 20th Century Men is the type of book that births big ideas through the science-fiction form. I would argue that these types of books – both graphic and prose – are the truest examples of science fiction as a diverse genre, while there are other perfectly fine stories out there labeled as science fiction and that succeed in telling a story with science fiction overlays. There is, I would contend, a fundamental difference between a story that uses science fiction elements as a unifying device and a book like 20th Century Men that embraces the totality of the genre and elevates it’s tropes and forms to the extent that it can only truly be told using those very tenets.

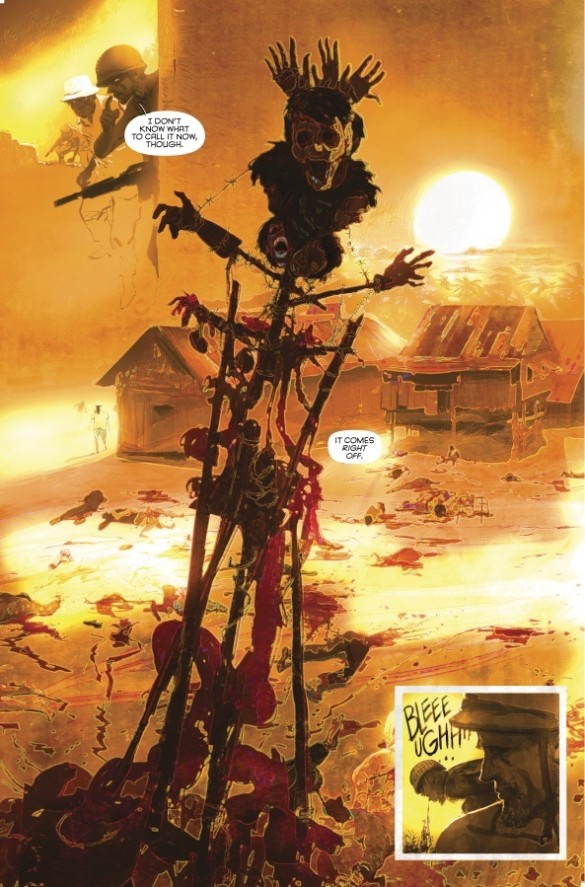

The story begins in some version of Vietnam. 20th Century Men inhabits a recognizable world, one with more overarching similarities than differences to our own. One of the things a reader will notice as they page through this issue is that Stipan Morian alters his artistic design for the different story lines and settings within the book. The opening feels painterly with a definite nod to impressionism. Morian will employ a type of painted realism for a good chunk of the book, but he will intersperse it with a distant kind of monochrome for the tragic early days of Platanov, our protagonist of sorts. Camp’s story jumps around to the highlights of the Cold War – from Vietnam we travel to 1948 Moscow before making our way to Kabul in 1987, Russia in 1968, and San Francisco in again 1987. I appreciate how distinct the feel for each of these settings is thanks to Morian’s unique touches that change the tone of each mini-story.

Camp embraces tropes of the superhero genre to tell this story, namely that of the “super-soldier.” The early days of superhero books are of course rife with the patriotic appropriation – or perhaps more fittingly, conscription – of superheroes for a war effort. Throughout the silver and bronze ages, superheroes were often stand-ins for geopolitical commentary. Camp pulls at some of these strings, and one catches different glimpses of the motif. Camp’s Platanov recalls elements of the most famous super-soldier of them all, Captain America, but there are also hints of the way Moore played with the notion of superheroes as agents of the state in Watchmen, and further connections to the aforementioned conscription of superheroes in the pages of All-Star Squadron or Invaders. Camp isn’t necessarily creating a pastiche, but rather embracing various characteristics of the super-soldier concept to create commentary laced with some clear deconstruction. There are elements of both Platanov’s visual characterization – that of a genius donning a robotic suit of armor – that obviously nods at Tony Stark while also winking at characterizations of both Dr. Doom and Reed Richards. Predominantly, though, 20th Century Men seems most rooted in the realism of DC’s war comics – Sgt. Rock, G.I. Combat, and modern incarnations of Unknown Soldier (to which the series has already drawn some comparisons).

It is this component that gives Camp and Sorian’s story it’s grounding. Camp is trying to tell a fantastic story about the real world, deliberately blurring the line and creating an alternative history scenario that feels very familiar. The realist grounding of the settings allows Camp to muse on what might have been had neo-liberalism developed a super-soldier component. For comics fans, the premise of this story might feel like an answer to the open-ended, “what if Tony Stark had gone all in.” Bigger than that, though, it is fundamentally a story of combat and the chess game of hegemony that dominated Cold War politics. Camp’s skill here is that he is able to create this overarching narrative of geopolitics that is driven by the will of one particular man and his own interpersonal relationships. As such, 20th Century Men is also a meditation on the great man of history theory.

20th Century Men doesn’t overtly bill itself as a superhero comic. And to be fair, it shouldn’t. It is a post-superhero superhero book. Camp’s premise very much rests on the idea that the reader is coming into the book with at least a basic understanding of superhero comics and a working knowledge of late 20th century diplomatic history. And if you can enter with those minimum prerequisites, you’re free to immerse yourself in the world where the worst impulses of neo-liberalism have commingled with a Marvel comic gone awry.

Twenty plus years removed from the turn of the century, it’s easy to forget about the kind of anxiety that permeated the late 80s before the fall of the Soviet Union. What seems like a foregone conclusion now was not in the vocabulary then. I was seven when the Berlin Wall fell, and even my immature mind understood the magnitude and, more importantly, the perceived impossibility of something like that happening only a year before. But the Berlin Wall and the Soviet Union both fell apart three decades ago. The idea of the cold war, and the attached ephemera - the kind of fine-line diplomacy-espionage hybrid – seems to scratch at the back of Camp’s head. He also explores similar themes in his other current series, Agent of W.O.R.L.D.E, but it is 20th Century Men that he chooses to mirror the real world with more deliberate precision. With only one issue in, it’s hard to speculate exactly what Camp and Morian are getting after. It is easy to think of this story as allegory, perhaps a cautionary tale, maybe even a deconstruction for it's own good. Regardless, I find something compelling about the reckoning Camp and Morian call down.

Comments ()