The American Dream at the End of Old Hollywood in Sammy Harkham’s Blood of the Virgin

Seymour seems to be searching for something but if you asked him, I don’t know if he would be able to articulate what it is.

In Sammy Harkman’s Blood of the Virgin, there are two fascinating interludes inserted into the story. The first is about a young man in 1915 Arizona, a journey that eventually leads him to Hollywood and an old age of petty rivalries. The second follows a young woman in 1942 Budapest and her life as a mother, her struggles with the emerging World War, and eventually her escape from a Nazi concentration camp. There are connections to Harkham’s larger story about a movie editor, his wife, and the humdrum life that they live but these interludes contrast with that couple Seymour and Ida’s lives, showing that something is missing from them, a void that the couple can’t even identify because they barely recognize that something is even supposed to filling that void.

In 1971, the last vestiges of the old Hollywood studio system were the B-movie exploitation houses, the production line assembly outfits that shot movies quickly and cheaply but still with an eye on craft that could only work in this kind of system. These people weren’t creating Bonnie and Clyde or The French Connection. They were following more in the footsteps of the Hammer horror films, creating horror movies to thrill a specific audience that they knew would turn out for their stuff. Maybe by today’s standards, we’d call them “schlock” but this was still a business and these people were still professionals. Well, at least a lot of them were. Seymour, an Iraqi Jewish immigrant, was one of those professionals, a film editor for one of the going-out-of-style production houses. He’s got a wife and a newborn at home and he’s just sold his first script to his boss. Life should be good but none of this is going the way he thought it would have.

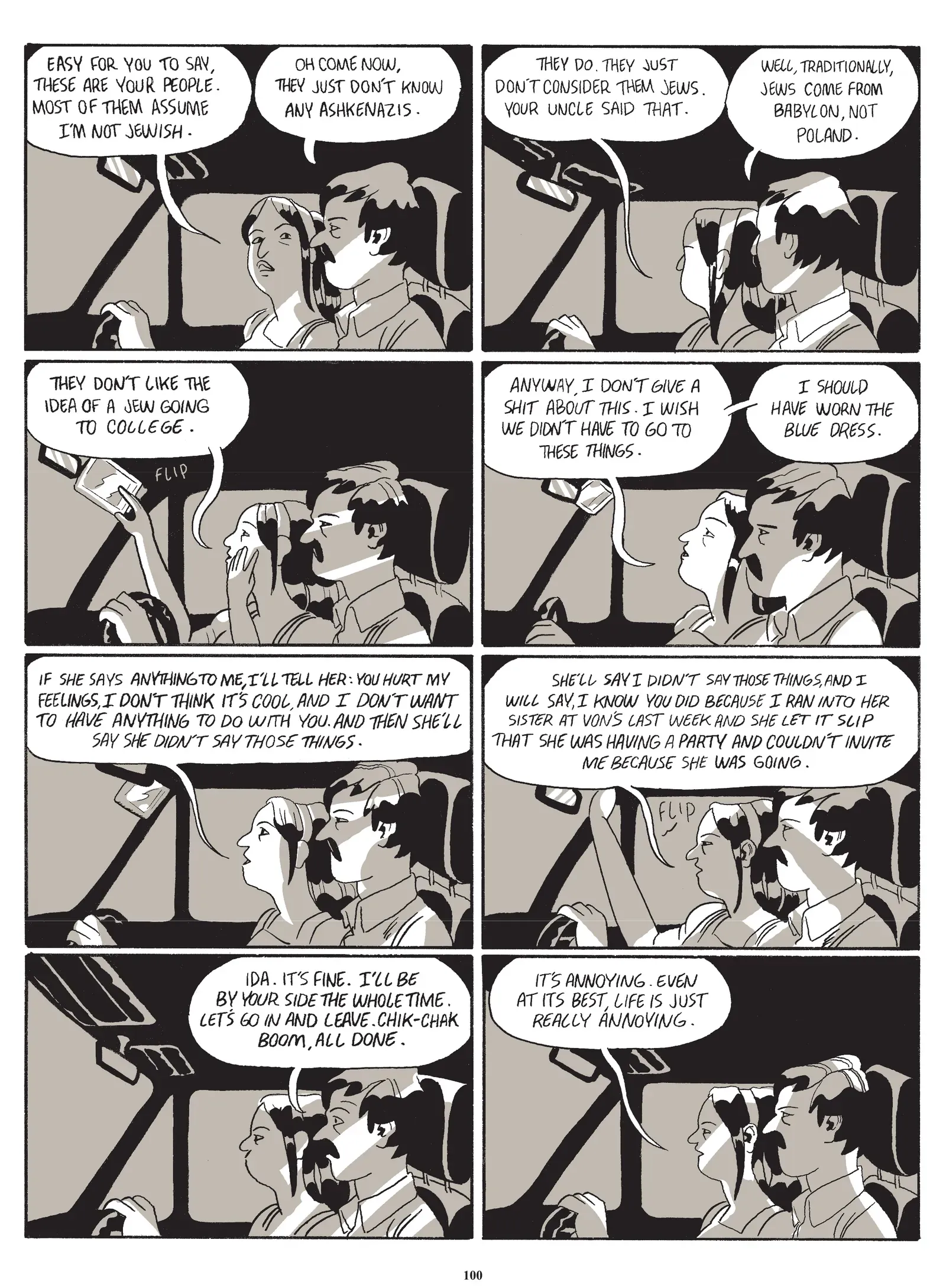

A wife, a kid, a steady job, and the opportunity to tell his story should be the American dream. It’s as American as apple pie but Harkham peppers his stories with the subtle (and a few not-so-subtle) reminders that both Seymour and Ida are immigrants. They’re not strangers to this country but it’s important to recognize that they’re coming at this dream from a different point of view, a foreign one that’s colored by its own unsaid biases and perspectives. It’s the American Dream circa 1971 from the point of view of immigrants. Harkham weaves these perspectives throughout the story, rarely making them the main throughline of the book but having them be present just enough to remind you of the outside viewpoints at work.

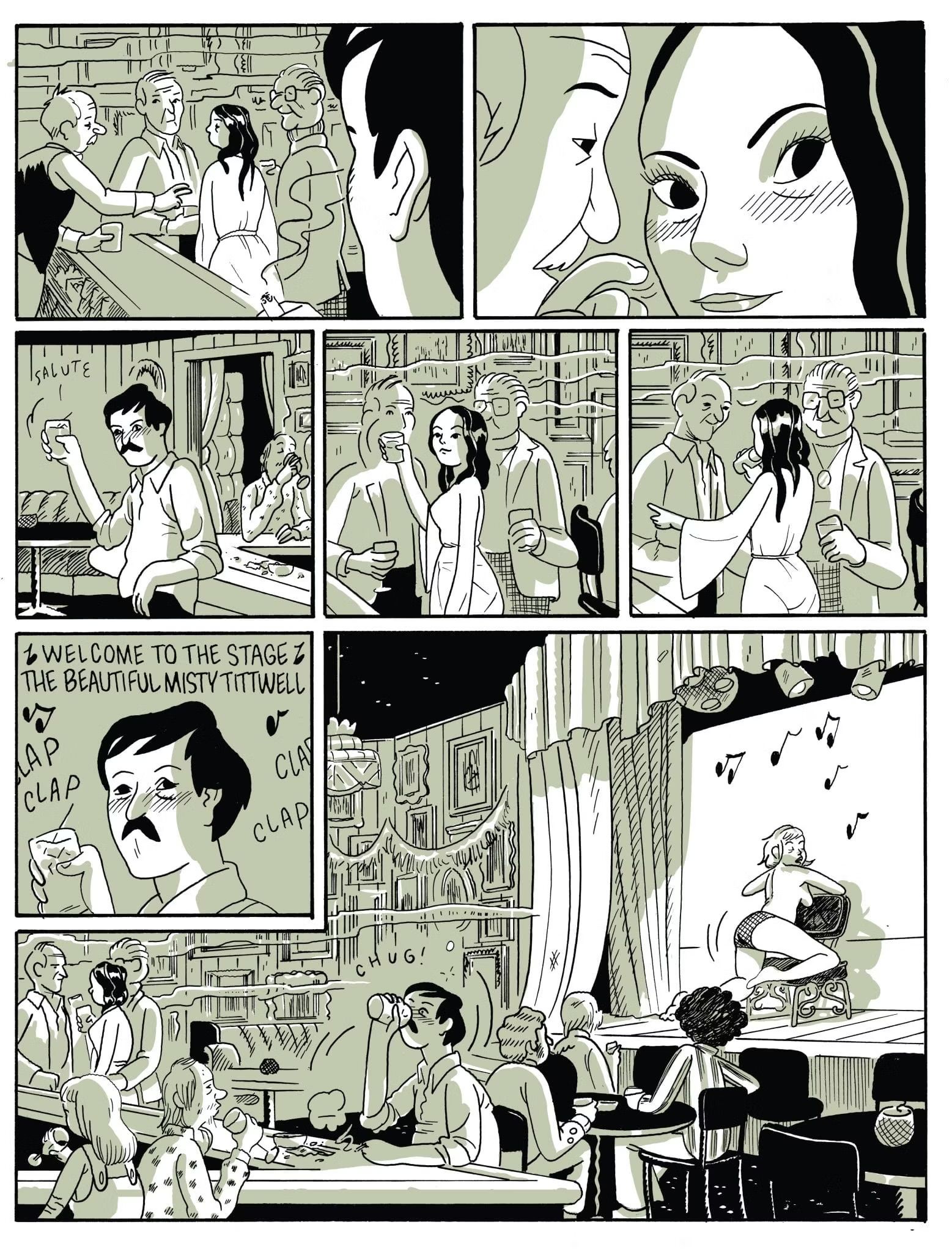

Seymour seems to be searching for something but if you asked him, I don’t know if he would be able to articulate what it is. Ida may be better at defining her longings but maybe those would be more defined by opposites of her life now. Some opportunities open up for both of them, maybe to the detriment of their marriage but good for their own mental health and wellbeing. There’s a view of true happiness just within reach for both of them but the other isn’t in that view. Call them dalliances or affairs or maybe even true love but there’s something just outside of Seymour and Ida’s reach that leaves them stuck in place in a marriage that’s more driven by responsibility and proximity than by love.

Early in the book, Harkham has these two sequences where he just really gets into the moment— one of Seymour cooking dinner and another describing how a special effect of a melting head works. He dials into these sequences in great detail fairly suddenly, creating two tiers of 1”x1” panels to practically give the readers a how-to. I think I may make Seymour and Ida’s chicken & rice recipe next week just for a good, easy meal. While he doesn’t return to this kind of detail anywhere else in the book, they demonstrate perfectly just how Harkham is willing to allow the story to show him just how dense each page needs to be.

Some panels are filled with only 4-5 big, expansive panels to create different emotional beats. These pages often show the size of Seymour’s world and just how small he is in it or at least how small he feels in it. Other times, they open up the world and show how much of it there is for Seymour and Ida if only they would open their eyes. There are other pages that he packs with panels, creating the tension of a world closing in on Seymour or showing the flow of time and how much life is happening around this couple. When you flip through other comics, the pages look the same— the same number of panels, the same layout, the same pace happening page after page after page. Harkham knows how to measure out the page for the greatest emotional impact while measuring out how the readers experience time with Seymour and Ida.

Going back to those interludes about the film industry and World War II, you can see Harkham doing the same thing narratively that he’s doing with the visual structure of his story. He dives into these experiences and then pulls out of them, offering this rich story that extends beyond Seymour and Ida but is explicitly about them and their lives. But in these interludes, we see a drive and need to live that’s not present in Seymour or Ida’s life. As they’re the benefactors of these interludes, they settled into a complacency in 1971 which is a luxury not allowed to these people during the first half of the Twentieth Century.

In Blood of the Virgin, Harkham tells this very human story of two people looking for some kind of contentment; it’s not necessarily happiness that’s part of this dream but more like a sense of peace or even comfort in their marriage. But even that may be something different for both of them; Seymour and Ida’s peace aren’t necessarily the same thing or even compatible things. As the two have opportunities to embrace change, to move on with their lives, Harkham recognizes how hard that is to do. We may say we want change but do we want to put in the work for it? I don’t think that Seymour or Ida want to put that much effort into moving on with their lives.